There was a small renaissance in science fiction movies in the early '50s, aside from the space operas and creature features, there were politically resonant, big budget titles like Robert Wise's The Day the Earth Stood Still. How and why science fiction films took themselves seriously isn't hard to understand if you just look at the headlines from the moment the film began production to after it hit theatres.

Screenwriter Edmund North was working on the script for the film in the first two months of 1951, at the beginning of the first full year of the Korean War. The year began with Chinese and North Korean forces capturing Seoul, and on January 11th a report was delivered to U.S. president Truman by the National Security Resources Board recommending the expansion of the war to the bombing of China and even a potential nuclear strike on the USSR.

Just two weeks after North delivered his final draft, the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg began; the Soviets had detonated their first atomic bomb just a year and a half earlier, and they would test two more weapons in September and October of that year. Two days after filming began on April 9, Truman relieved Gen. Douglas MacArthur of his command of the Korean War. As filming was wrapping in May, the U.S. was testing its first thermonuclear warheads at Eniwetok Atoll. Just a few days after production wrapped Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean defected to the Soviet Union.

That year, the U.S. Census department took delivery of the UNIVAC 1 computer from Remington Rand and the USSR sent two dogs, Dezik and Tsygan, on a sub-orbital spaceflight. In September, just a week after the film was released, the Chinese army took Lhasa, the Tibetan capital, and the UK began an economic boycott of Iran. In November, British troops were sent to suppress riots in the Suez Canal zone and the U.S. military held exercises rehearsing nuclear war in the Nevada desert. At the end of the year the Marshall Plan came to an end after spending more than $13.3 billion rebuilding Europe.

It was an eventful year in Hollywood sci-fi: while Wise was filming The Day the Earth Stood Still, RKO released The Thing from Another World, and two months after Wise's film came out George Pal's When Worlds Collide hit the theatres. 1951 was also the year that saw the publication of Stanislaw Lem's The Astronauts, John Wyndham's The Day of the Triffids and two Arthur C. Clarke novels: Prelude to Space and The Sands of Mars. Whatever was happening on the planet that year, people were also looking to the stars, albeit with no small amount of anxiety.

A modern viewer will watch the opening scenes of The Day the Earth Stood Still with déjà vu, as telescopes and radar stations across the world, from Australia to India to France to the UK track a mysterious object moving at rapid speed across outer space, hurtling straight towards Earth. It's a trope now, repeated like a ritual at the start of nearly every alien invasion/world-destroying asteroid story. It originated, of course, with H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds, but this was probably the first time it appeared onscreen.

Newsreaders announce the alien object's progress in a series of cameos by actual journalists, including Kenneth Kendall of the BBC, Elmer Davis of ABC, NBC's Drew Pearson and H.V. Kaltenborn and Gabriel Heatter of the Mutual Broadcasting System. Their appearance would lend the film a documentary feel that was cited frequently in reviews. The object – a classic flying saucer – finally appears in the sky over Washington DC, and comes to a rest in the middle of the baseball fields on the Ellipse by the Mall, just across from the White House.

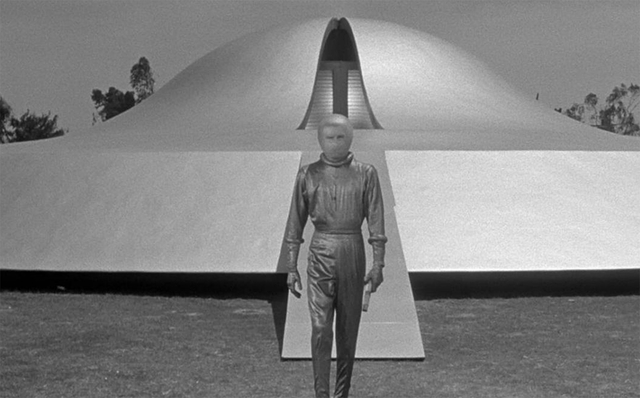

The spaceship is ringed by police and troops in tanks – along with a crowd of gawking citizens held back just yards away; one notable change with more recent cinematic iterations of this alien first encounter is that the public would be cordoned off miles away, if they were able to enter the official quarantine zone at all. We have, over seven or so decades, come to expect a more heavy-handed intrusion of authority in our lives. Suddenly a door opens in the craft and a huge metallic robot presents itself, followed by a man in a silver suit and helmet. He takes an object from his suit and tries to present it to the military but a trigger-happy GI shoots it out of his hand and wounds the alien emissary.

The robot's visor opens and a blinding white ray dissolves the guns and tanks closest to the ship, but the wounded alien gives an order and the robot closes his visor and becomes inert. So far nearly every step in this close encounter plays out like canon, as it's been replayed over and over in whole or in part in films like Independence Day, Battleship, District 9, Battle: Los Angeles, Arrival and – as satire – in Mars Attacks, at which point it had already become a cliché.

The alien is taken to Walter Reed Army Hospital where he's revealed to be perfectly human in form, though able to heal his wound with remarkable speed. He introduces himself as Klaatu (Michael Rennie), and though he asks to speak with the president, he's graced with a visit from Harley (Frank Conroy), the president's secretary, who treats the alien visitor like any diplomatic envoy who overestimates his importance.

The dialogue between Klaatu and Harley, as written by North, is one of the touches that gives The Day the Earth Stood Still a gravitas that made it stand out among the other sci-fi pics being produced by Hollywood at the time:

Klaatu: I want to meet with representatives of all the nations of the earth.

Harley: I'm afraid that would be a little awkward. It's completely without precedent.

The president's secretary – you assume he's a seasoned political player, perhaps a diplomat, or a party loyalist whose bureaucratic skills have made him essential to mediate between the man in the Oval Office and the powers and players behind him – walks a fine line, trying not to condescend to this interplanetary emissary while making him aware that he's an outsider to the system to which he's trying to make an appeal and needs to respect the process.

Harley: I want to be frank with you, Mr...Klaatu. I mean, Klaatu. Our world at the moment is full of tensions and suspicions. In the present international situation, such a meeting would be...quite impossible.

They discuss the United Nations, and Harley attempts to impress upon the visitor that there are "evil forces" at play which Klaatu can surely appreciate, but the alien replies curtly:

Klaatu: I'm not concerned, Mr. Harley, with the internal affairs of your planet. My mission here is not to solve your petty squabbles. It concerns the existence of every last creature on Earth.

Harley suggests he speak before the General Assembly of the UN, adding that this wouldn't include every nation on the planet. Klaatu asks him to convene a meeting with every head of state, but Harley tells him with an impressive impersonation of sorrow and regret that he doesn't understand how impossible it is, that "they wouldn't sit down to the same table."

Realizing that he's getting nowhere, Klaatu's demeanor transforms into bemused disinterest, and despite orders that he's to be confined to the hospital, he easily escapes wearing a suit he took from a storage room and heads out to observe humanity up close.

He ends up in a rooming house – apparently Washington DC, a boomtown in peace as well as war – that is still suffering from the kind of housing shortages that provided the setting for George Stevens' 1943 comedy The More the Merrier. Among the tenants is Helen (Patricia Neal), a widow who works as a secretary in the Department of Commerce, and her young son Bobby (Billy Gray).

Hiding in plain sight, Klaatu – calling himself Carpenter – bonds with Bobby, visiting the boy's father's grave in Arlington (he was killed at Anzio). Helen's steady man Tom (Hugh Marlowe) isn't as impressed, sensing an attraction – platonic, but crucial to the plot – between her and the mysterious lodger who carries around a pocketful of diamonds in lieu of cash.

Klaatu learns from Helen and Bobby about Prof. Barnhardt (Sam Jaffe), an internationally renowned scientist who lives near Helen's office. Movies, then and now, retain a touching reverence for these big brains – the "world's smartest man" – whose judgment can be trusted as, so the assumption goes, their commitment to facts and the scientific method puts them above both mainstream ignorance and superstition and the self-interest of politics and commerce. The last public intellectual who lived in such high regard was probably Steven Hawking, but COVID-19 probably dissolved this kind of trust, perhaps forever.

Klaatu leaves a calling card for the professor – a solution on his blackboard to the "Three Body Problem" that only recently escaped the realm of theoretical physics and went mainstream with a series of novels by Chinese sci-fi writer Liu Cixin (and currently being adapted into a Netflix miniseries). Summoned by Barnhardt, Klaatu reveals his identity and has the professor promise that, in lieu of the world's heads of state, he'll arrange a meeting with the globe's best minds but adds that it would be useful if the alien visitor could provide a peaceful demonstration of his capabilities. Klaatu obliges by programming his spaceship to selectively black out the globe for a half hour at noon EST – turning off electricity and every engine and motor except for crucial items like hospitals and planes in flight.

Unfortunately Klaatu is followed by Bobby as he visits his spaceship and the boy tells Tom and his mother. They dismiss his story until Tom finds a diamond on the floor of Klaatu's room; learning this, Klaatu visits Helen at her work, just as his global blackout begins. Stuck in an elevator, Klaatu is able to convince her not only that he's the alien on the lam, but that the robot, Gort, has the capability to lay waste to the planet if Klaatu is harmed.

Julian Blaustein, a producer at 20th Century Fox, wanted to make a film about Cold War paranoia cloaked in sci-fi trappings, and had the studio's story department comb through hundreds of novels and short stories until he found "Farewell to the Master", a story by Harry Bates published in Astounding Science Fiction in 1940. Screenwriter Edmund North was assigned to the project and kept Klaatu and his giant robot companion but jettisoned nearly everything else.

Robert Wise, a talented director who began his career with producer Val Lewton – replacing the original director of The Curse of the Cat People and going on to make Mademoiselle Fifi and The Body Snatcher for Lewton – had established his reputation with some solid film noirs (Born to Kill, The Set-Up, The House on Telegraph Hill) and Blood on the Moon, a "psychological western" with Robert Mitchum.

Wise – who would become famous for West Side Story, The Haunting and The Sound of Music and return to science fiction in the '70s with The Andromeda Strain and Star Trek: The Motion Picture – understood that the engine of the plot of his sci-fi story was an urban thriller, as Klaatu and Helen rush to seek refuge with Barnhardt while the military close the net around them on the streets of Washington, finally cornering Klaatu and shooting him dead.

The chase is set in motion when Tom takes Klaatu's diamonds to be appraised and is told that they're unlike any gem on the planet. He connects the dots and is about to call the authorities when Helen arrives and tries to dissuade him. The film's already set her up to choose between Tom and Klaatu, and when he tells her that turning the alien in will let him "write my own ticket," Helen realizes the mistake she's made choosing someone all-too human.

North had tried in his screenplay to hide its principle metaphor – the Christ-like role of Klaatu and the Godlike powers of Gort – but he left big tells all over the script, like Klaatu taking on the name "Carpenter". In any case, Joseph Breen of the Code-enforcing Motion Picture Association of America took umbrage at Gort's ability to resurrect Klaatu's corpse and had Blaustein insert a line where the alien explains to Helen that he has only been revived temporarily, and that the power of resurrection "is reserved to the Almighty".

Knowing that Gort will go on a vengeful rampage if Klaatu is killed by the humans, the alien tells Helen to rush to the spaceship if anything happens and say three words to the robot: "Klaatu barada nikto". Neal recalled years later, in a documentary about the film made for its Laserdisc reissue, and included again on a 2002 DVD reissue, that she had a hard time keeping a straight face with the line, and that she considered the whole job a silly piece of work until she finally saw the finished picture.

Along with North's dialogue and Wise's tasteful, purposeful direction, Neal's performance is probably one of the reasons why The Day the Earth Stood Still rose above rank-and-file sci-fi pictures, both when it was released and in subsequent years. Never an ingenue, the actress projected an intelligence and low-key, mature sexuality that radiated in her best performances, in pictures like The Fountainhead, A Face in the Crowd, Breakfast at Tiffany's and Hud.

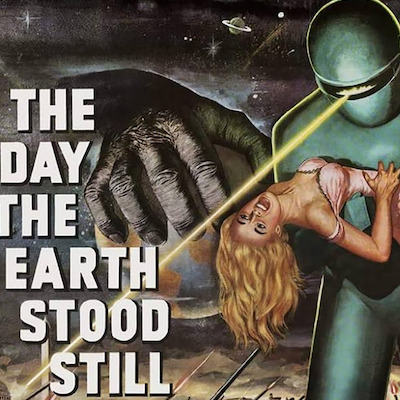

Neal was, nevertheless, subject to the treatment doled out to heroines in sci-fi and horror; she's picked up and carried into the saucer by Gort after she gives him the disarming password, despite being sympathetic to the alien mission and able to walk on her own. In one version of the film's poster Neal is shown as a classic damsel in distress, prone and about to scream, and wearing a red strapless cocktail dress that appears nowhere in the sensible Helen's wardrobe during the film. In other posters a huge, coarse black hand is shown closing its fingers on the Earth.

It was inevitable that The Day the Earth Stood Still would get re-made, and the casting choices in the 2008 version are telling. Helen, played by Jennifer Connolly, was promoted to a Princeton astrobiologist, and Bobby was race-swapped by nepo baby Jaden Smith as Jacob, Helen's stepson. Harley the president's secretary became Kathy Bates as the Secretary of Defense while John Cleese played it straight as Professor Barnhardt.

The remake's special effects got a hypertrophied upgrade by Weta Digital, who turned the spaceship into a massive swirling orb and Gort into a towering giant built of nano-particles. In the original Michael Rennie, an unknown, was cast over Spencer Tracy and Claude Rains by Blaustein, who knew that the moment a recognizable movie star walked out of the spaceship the audience would have a hard time believing in the picture's alien hero.

The remake upgraded Klaatu, not just by giving him powers that far exceeded Rennie's mere facility with locked doors, but by casting Keanu Reeves. Reeves, a wholly likeable celebrity and a bona fide movie star, is also an undeniably poor actor, but his Klaatu is somehow entirely convincing as an alien doing a mediocre impression of a human being.

It's not surprising, given Blaustein's ambitions for his picture, that the whole of the original version builds to the final scene where a resurrected Klaatu addresses Barnhardt and the crowd of scientists and "great minds", laying out an ultimatum for Earth before he leaves. Despite his indifferent or outright lethal treatment by the authorities, but thanks to his friendship with Helen, Bobby and the professor, Klaatu gives us one more chance.

The federation of civilizations that sent him were happy to ignore an inconsequential planet like Earth, he says, until we developed atomic weapons and the rockets that could send them into space and threaten other planets. We have a choice to submit to the same agreement that binds the other civilizations together. "That does not mean giving up any freedom," Klaatu tells us, "except for the freedom to act irresponsibly."

To that end they have conceded ultimate authority to a race of robots who have an irrevocable mandate to wipe out any planet that becomes aggressive. "We do not pretend to have achieved perfection," he says," but we do have a system, and it works." They have, in essence, given Godlike power to Gort and his race of spacefaring robot police – the twist at the end of Harry Bates' original story that was retained by North.

This might have seemed like a sane, enlightened option in the aftermath of two world wars, and when an organization like the United Nations was regarded as optimistic. Seven decades later, the UN has long proved itself unfit for purpose and whatever "peace dividend" we imagined at the end of the Cold War has been spent to no discernible advantage to either winners or losers.

Our "great minds" either aim to escape into space or rewind technological progress to some depopulated proto-industrial utopia of their own imagining. And every year sees the release of yet another movie imagining an alien invasion that unites us in resistance or an asteroid that will bring on a hard reset. Our tragedy is not that we have run out of options, but that we lack the imagination to come up with new ones.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.