The death of industrial music pioneer and perpetual provocateur Genesis P-Orridge got me thinking.

Not that I liked his "music." (I decline to use his preferred pronoun, "s/he.")

But because P-Orridge died at age 70, I enjoyed picturing bummed out young "trans" poseurs learning through these obituaries that body modification and "gender fluidity" weren't their ideas.

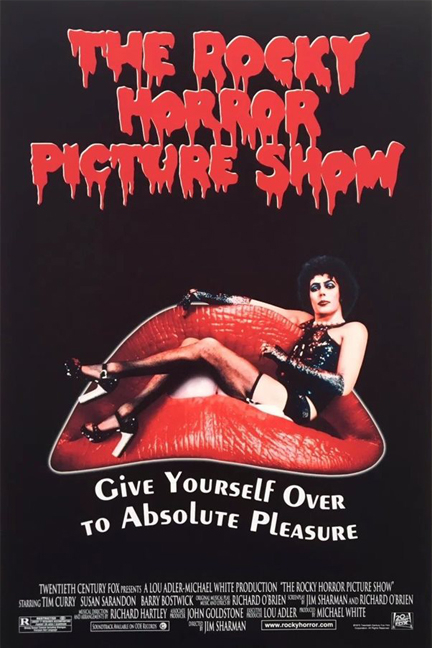

I also thought — not for the first time since the advent of what Steve Sailer calls "World War T" — about The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975.)

The enduring cult film started out as a campy London stage musical that spoofed science fiction B-movies while dialing up the tropes of then-trendy glam rock.

"Space age" androgyny, often awkwardly slapped on top of incongruously macho, stomping tunes. (Think: Gary Glitter, Slade, Ziggy Stardust-era Bowie, Alice Cooper).

The plot is simple: Stranded clean-cut newlyweds seek shelter at the castle of Dr. Frank-N-Furter (Tim Curry), "a sweet transvestite" from the planet Transylvania. He and his minions suck the couple into their hedonistic lifestyle, but the party can't last forever...

After the film version flopped in wide release, the Waverly Theater in Greenwich Village showed it as midnight movie (a novelty it had adopted in 1970) along with three other Manhattan theaters.

But audience participation set The Rocky Horror Picture Show apart from previous 12 o'clock cult films like Harold and Maude and El Topo. What began as a single, spontaneous outburst from one bored regular — a Staten Island kindergarten teacher, no less — mutated, then hardened, into a codified script of call-backs, and eventually, simultaneous, costumed "shadow cast" performances in front of the screen.

In high school in the early 1980s, I spent many Saturday nights acting up at midnight Rocky Horror screenings, too.

Schoolmates with stricter parents came to my apartment (under the pretext of a sleepover) to put on weird outfits and thick makeup. My mom filled twist-tie baggies with rice and toast (to throw at the screen on cue) while expressing embarrassingly unconcealed delight that her shy, strange daughter had actual friends.

(That I lived a block away from the city's only rep theater didn't hurt: we could walk there without enduring the abuse hurled at "weirdos" in our blue collar town.)

My friends and I loved the sing-along songs, the quirky costumes, and the safely subversive fun of staying up late, and yelling and making a mess in a movie theater.

Not a few "queer" folks credit The Rocky Horror Picture Show with awakening, or legitimizing, their sexuality when they were still closeted adolescents. Being straight (and back then, as virginal and clueless as most of my friends), I don't recall anything of the sort. The movie seemed only slightly raunchier than Monty Python's Flying Circus or the Carry On... movies that aired steadily on TV at home.

So the sight of some guy wearing fishnets onscreen (even one as transcendently mesmerizing and un-self-conscious as Curry) was, well, cool but whatever.

Of all the songs (and I can still "sing" them all) the poignant "Over At The Frankenstein Place" was my favorite – almost a lullaby. As it played, we raised our candles and cigarette lighters, and rocked back and forth in somber unison:

In the velvet darkness

Of the blackest night

Burning bright

There's a guiding star

No matter what

Or who you are

There's a light

Over at the Frankenstein Place

There's a light

Burning in the fireplace

There's a light, light

In the darkness of everybody's life

There was a lot of darkness in my life. Going to Rocky Horror was one of my "lights over at the Frankenstein Place," too. But not, oddly enough, the movie itself.

Fans often sum up the film's message with one of its lyrics: "Don't dream it. Be it." As someone who walked around downtown in Slits-inspired gear, I could relate. But even then, I sensed the flaws in such a philosophy, especially when it came from the red-lipsticked mouth of the movie's main character.

Frank-N-Furter is the archetypal horror "creator," but in a twist, he is the true monster. It went over my head at the time that he not so much seduces the newlyweds as rapes them. But I did notice that he treated his minion, friends and lovers like dirt.

As much as he claims to celebrate "freaks," the "monster" Frank creates is the mesomorphic epitome of traditional masculinity, beside whom the diversity and eccentricity of Frank's loyal hangers-on is cast into high relief.

Frank boasts of having not only cast aside his previous "favorite," the Fifties rocker Eddie (played by Meat Loaf), but of murdering and cannibalizing the poor guy. The homely Columbia, who'd pined for Eddie, sounds one of the first notes of doubt:

It was great when it all began

I was a regular Frankie fan

But it was over when he had the plan

To start working on a muscle man

As the chaos in the castle descends from fun into felonious, two of Frank's lackeys, Riff Raff and Magenta, confront him, armed with laser guns:

Frank-N-Furter, it's all over

Your mission is a failure

Your lifestyle's too extreme

I'm your new commander

You now are my prisoner

And the uptight criminologist-narrator, who we've been drowning out with screams of "BORING!!" every time his face appears on screen, has the last sad word:

And crawling on the planet's face

Some insects called the human race

Lost in time

And lost in space... and meaning.

Rocky Horror fans, despite having seen it hundreds and sometimes thousands of times, seem willfully oblivious to the movie's cautionary coda.

As a punk whose disgust with hippies and their "do your own thing" philosophy — the same one that had broken up my home, twice — I was impressed that Rocky Horror seemed to be, perhaps unintentionally, a condemnation of the very ethos that made its "shocking" excess possible.

Recently, some admirers of the film have reluctantly acknowledged this underlying theme, along with the fact their one-time role model was a creep. In the lingo of our times, Frank-N-Furter is "problematic."

As for me, I remember when pansexual men in drag, bullying all within their orbit to obey their commands or else, were confined to screens big and small. We "visited" these colourful, carnival characters voluntarily once a week, then went back to our straight (or semi-straight) lives.

I feel foolish even having to point out that no one ever brought children to our past-their-bedtimes midnight parties.

Now, it's midnight and Mardi Gras, Christmas and Halloween, every minute of every hour of every day. Predictably, this pre-adolescent notion of "paradise" has turned out to be the opposite of "fun."

The death of Genesis P-Orridge prompted some laudably frank discussion of his proclivities for violence, diva-level tantrums and, well, treating his friends like dirt.

But we still don't have enough Riff Raffs and Magentas out there, willing to shake off their shackles and say, "Enough."

Except, ironically, this guy:

The mastermind behind Rocky Horror, and the original Riff-Raff, Richard O'Brien, has long labeled himself "third sex." If anyone can claim original gangsta trans cred, it's him.

And yet, here he is:

"I agree with Germaine Greer and Barry Humphries," he said recently. "You can't be a woman [just because you've had a sex change].

"You're in the middle and there's nothing wrong with that. I certainly wouldn't have the wedding tackle taken off.

"That is a huge jump and I have all the sympathy in the world for anyone who does it," O'Brien added.

"But you aren't a woman."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think in the comments. If you want to join in on the fun, make sure to sign up for a membership for you or a loved one. To meet many of your fellow club members in person, join Mark along with Douglas Murray, Michele Bachmann and several others aboard our upcoming Mark Steyn Cruise down the Mediterranean.