What shade of blue is that?

I don't think I've seen it in a movie before. Maybe in an old Disney cartoon.

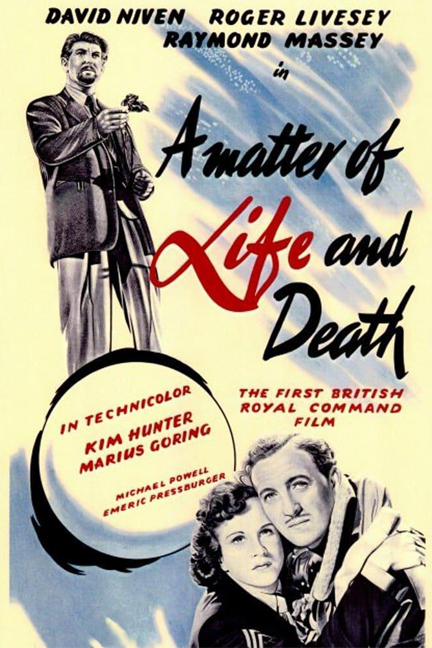

But A Matter of Life and Death is a Powell and Pressburger film, so naturally it doesn't look like anything else.

"This is the universe. Big, isn't it?" asks a voice frosted with English understatement.

We're on a narrative tour of galaxies and solar systems, eventually hovering over a too-green Earth.

(Arthur C. Clarke consulted on this sequence, but in 1948, not even the guy who conceived of the satellite managed to accurately predict the "Blue Marble," which his own invention would reveal to us in the near-ish future.)

We hear radio transmissions as they make their way through space — "This was their finest hour" and such, but one more mundane as well: A woman's voice, American (Kim Hunter):

"Request your position. Come in, Lancaster."

The pilot of that Lancaster (David Niven) — the sole survivor of his crew, his plane in flames and falling fast — is all business:

"Position nil. Repeat, nil. Age 27. Very important. Education: Violently interrupted. Religion: Church of England. Politics: Conservative by nature, Labour by experience.

"'Give me my scallop-shell of quiet/My staff of faith to walk upon

'My scrip of joy, immortal diet/My bottle of salvation,

'My gown of glory, hope's true gage/And thus I'll take my pilgrimage.'

"Sir Walter Raleigh wrote that. I'd rather have written that than flown through Hitler's legs."

While countless movies have depicted love at first sight, A Matter of Life and Death is about, among many other things, love at first sound. The American radio operator, June, and the English pilot, Peter, fall for each other over the radio.

A Matter of Life and Death is a fantasy inspired by a true story; Heaven is black and white while life among the living is shot in Jack Cardiff's awe-inspiring Technicolour; it is masterpiece that was commissioned by the State; it concerns (again, in part) what we used to call (within living memory), "nationality": the self-evident differences in behaviour, customs and worldview of citizens of various countries — while, ironically, the actor playing the ultimate American was Canadian (Raymond Massey, an old hand at that), while the quintessential French aristo fop is portrayed by an Englishman.

(As if to prove these differences exist, the movie's title was changed to Stairway to Heaven for U.S. distribution; someone or other believed that Americans would reject a film with the word "death" in the title.)

Miraculously, Peter doesn't die. He washes ashore, and, who does he see cycling past him but June, on her way to the great old English house at which she's stationed. Neither can make sense of this turn of events, but don't try very hard to. They simply fall deeper in love.

But up in Heaven, Peter's survival is no miracle. They had nothing to do with it; rather, an English pea-soup fog prevented celestial minions from snatching him up at his appointed time, and the powers that be aren't amused by this wrench in their bureaucratic works. So they dispatch said French aristo fop (beheaded during the Revolution, and now a "Conductor") to Earth to tell Peter what's what.

But Peter has no desire to go to Heaven, having discovered heaven on Earth with June. Luckily, she knows a brilliant country doctor who happens to be an expert in neurology. Dr. Reeves (Powell and Pressburger regular Roger Livesey, of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp fame) is sure he can cure Peter of his hallucinations (and what we might today call PTSD) by, counterintuitively, playing along with them.

Oh yes, Peter has to be tried in Heaven, to make his case that now that he's fallen in love, he must be allowed to remain on earth. Of course, he must choose a wise man up there as his defence counsel. Let's all think hard and come up with the right fellow — right after you take this sedative. June and Dr. Reeves play their parts to perfection, even more so after Something Terrible Happens...

A Matter of Life and Death will bowl you over even if you don't know its origin story, but it's better if you do:

The film began as an expressly propagandist project. Jack Beddington, head of film at the United Kingdom's Ministry of Information, asked Powell and Pressburger over lunch: "Can't you two fellows think up a good idea to improve Anglo-American relations?" [Many readers are presumably familiar with the expression "overpaid, oversexed and over here."]

By the time they made "AMOLAD" (as all involved called it), the Kentish director and Hungarian screenwriter had twice exceeded their war-effort brief, with controversial results. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (...) – scandalised Churchill with its portrait of a good German and its mockery of a certain English bluster. And in A Canterbury Tale, Powell and Pressburger revelled in a twisted vision of old England at the near-gothic (but again comical) expense of the film's message about Anglo-American cooperation before D-Day.

It's easy to imagine the Archers (as Powell and Pressburger dubbed their partnership) muttering that no one had fully appreciated their previous war films, so why should they bother? Fortunately, they did.

It helps knowing all this going in, because a sub-theme in A Matter of Life and Death is the difference between the American and the English temperament, which, again, isn't the pressing or fashionable topic it once was. Modern viewers might be puzzled, rather than wryly amused, when the first Yanks we meet arrive in Heaven with no little bombast (and note the Coke machine).

This tension between two "tribes" is teased out during the Heavenly trial — conducted while Peter is undergoing a brain operation — when the American charged with prosecuting Peter and the Englishman he chooses to defend him debate the superiority of their own cultures, the better to decide if an American girl could really live happily ever after with an Englishman.

(SPOILER ALERT — this clip reveals the "Something Terrible Happens" twist).

By the way, the construction of that "stairway to heaven" (nicknamed "Ethel" by the crew) is a story unto itself. The statues you see along the left are those of the Great Men of History, one of whom, it may amuse you for various reasons to notice in an earlier scene, is Mohammed.

Unsurprisingly, the war years and just beyond witnessed a burst of films blanc, "whimsical visions of life that deal with the great beyond, the afterlife, heaven and hell. They are usually romances or light morality plays, sometimes satirical, often sentimental":

Here Comes Mister Jordan, I Married an Angel, Angel on My Shoulder, The Bishop's Wife, It's a Wonderful Life, and the American film which most resembles this one, 1943's A Guy Named Joe.

However, none of these come close to A Matter of Life and Death in terms of ambition, sophistication, intellectual heft, technical prowess and resonance.

There are many reasons to watch this movie, but the only way to do so if you wish to appreciate its greatness, is to view the 2017 Sony/Criterion 4K restoration, the result of a particularly painstaking process as it required handling both Technicolor film and black and white.

A Matter of Life and Death isn't currently streaming anywhere, but it has been known to air on TCM.

Wait if you have to.

Addendum:

I've been a professional writer for over 35 years, yet still experience a phenomenon that is crying out for one of those "foreign words with no English equivalent," like "wabi-sabi" and "tartle."

That is: the factoid or anecdote that inspired me to write a column in the first place doesn't make it into the column itself. Fortunately, these days I can plead "chemo brain."

(In Shrinkage, his must-read memoir about his fight against cancer — the chapter about the lost engagement ring is worth the price of the book — Bryan Bishop says one of his biggest regrets is not using "I have a brain tumor" as an alibi for awkward and embarrassing situations, whether or not it was strictly apropos.)

So last week I wrote a whole long thing about Brian Linehan and his wonderful interviews with celebrities, and forgot to mention that one of those interviews — with Steve Martin — gave 20-year-old me a perspective on life that has stood me in pretty good stead all these years.

Ironically, Martin's anecdote didn't appear in his much-later autobiography. I was dumbfounded, and frankly, put out. Why, I had practically lived by this story, calling it to mind countless times as I'd inched my way through existence.

Another of life's mysteries...

Anyhow, here it is.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think of this column below in the comments section. Beyond commenting privileges, membership in the Mark Steyn Club comes with a great many perks – from access to the entire SteynOnline back catalogue to invitations to exclusive Mark Steyn events. Pick up a membership for yourself or a loved one here.