Last week, in my look back at the movie version of the musical 1776, I mentioned learning, well into adulthood, that much of what I'd been told about American history wasn't true.

To be more specific, I found out that that left's narrative about America was largely libellous. That is, it fit the legal definition of "malice": Knowing information to be false but printing it anyhow, to further a grudge or agenda.

For instance: Everything I thought I knew about the Scopes Monkey Trial, an event used to ridicule American evangelicals for close to a century, was wrong.

Joseph McCarthy was (mostly) right.

The "research" touted by liberal heroes like Betty Friedan, Margaret Mead, Alfred Kinsey, Rachel Carson, and Mitch Snyder, to name a few — whose work fuelled societal upheavals that left numberless victims in their wakes — was conducted unethically or just plain made up.

Speaking of heroes, the left sure do love their "martyred" criminals, don't they? Turns out that contrary to popular belief, Alger Hiss was guilty. The Rosenbergs were guilty.

Sacco and Vanzetti were guilty too.

Theirs was the "trial of the century" of its time. In 1920, the two anarchists were convicted of murdering a guard and a paymaster during an armed robbery. Until their execution seven years later, the world's radicals orchestrated campaigns proclaiming their innocence — and condemning America's villainy for "persecuting" them.

Money was raised, of course, and petitions signed, and mass protests staged, with demonstrators numbering in the tens of thousands at any one time and place. Furious essays duelled in the nation's press, and many bad poems and songs were written (well into the rest of the century, because as I always say, "progressives" live in the past). Books too, of course, the most famous of which was a novel that touted Sacco and Vanzetti's innocence: Boston (1928) by Upton (The Jungle) Sinclair.

Sacco and Vanzetti's letters from prison became talismans for radicals around the world. Penguin released a commemorative collection on the 80th anniversary of the men's execution, hailing these epistles as among "the great personal documents of the twentieth century, (...) famous for the splendor of [their] impassioned prose."

Indeed, it became a fashionable article of faith that, surely, men who could write so affectingly couldn't possibly be guilty.

(By the way, this perverse "logic" isn't confined to the stupid, or even those of one political orientation: Norman Mailer and William F. Buckley were separately entranced by the writings of prison inmates, and campaigned for their release — only for these criminals to go on to harm more innocent people.)

Anyhow, it is one of Vanzetti's letters that sets the plot of The Male Animal (1942) in motion.

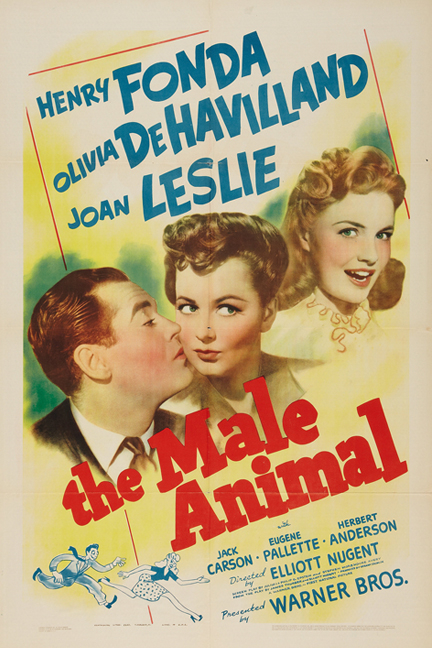

Originally a hit Broadway play by James Thurber and Elliot Nugent, the film concerns Tommy Turner (Henry Fonda), a college instructor who plans to read one of Vanzetti's letters to his English Composition class. When word gets out, the school's trustees, who've been zealously firing teachers suspected of being "reds," threaten Turner with the same fate.

Turner insists that he wants to read Vanzetti's letter merely to demonstrate that even someone who writes in "broken English" is capable of composing powerful prose. Politics has absolutely nothing to do with it.

Now, Henry Fonda could tell me, "My second of five wives DID NOT" — can't you just hear him? — "slit her throat with a razor after I demanded a divorce so I could marry a 20-year-old!" And I'd believe him.

And alas, in The Male Animal, Fonda's skill at conveying somber sincerity, arguably his greatest actorly gift, is deployed here — to return to that legal lingo — maliciously.

Professor Turner is a befuddled, cerebral naïf to be sure, but despite his, Penguin's, and any random radical's protestations, Vanzetti's letters are inescapably political, however majestic (or mediocre) one judges his style to be.

Turner is on a firmer foundation when he defends his choice on free speech grounds, and proclaims correctly that a college is precisely where any and all ideas should be presented and debated. I wish Thurber had chosen to emphasize that earlier and more often; Turner's ever-changing motives muddle the film's message.

Anyway, Turner does read the letter (as you had guessed, because Henry Fonda.)

Again, given James Thurber's one-time reputation as A Great Writer, I'm floored that he considered a drug addict the moral equivalent of a convicted terrorist, or thought name-dropping Karl Marx was any more ameliorative. Were those examples the best he could come up with? Contrary to Turner's fulminations, murder is neither a "personal habit" nor a "political opinion," but conveniently, Sacco and Vanzetti's actual crimes — the reason they were, you know, writing from prison — are never broached in the film.

Presented without such context, Vanzetti's musings about sacrificing his life for the causes of love and justice and the brotherhood of man duly render the formerly hostile crowd in the auditorium mute with admiration. Burly, cocky, all-American Jack Carson is made to whisper, "Is that it? That's not such a bad letter," so you know what you're supposed to think.

(Hit Broadway play or not, how this movie got green-lit by the staunchly anti-communist studio heads at Warner Bros., I'd love to know.)

Twenty years after The Male Animal was released, the leader of the Sacco and Vanzetti Defence Committee told writer Max Eastman that "Sacco was guilty but Vanzetti was innocent" — meaning, Vanzetti was an accomplice, which makes him, in fact, guilty under American law. A former member of the pair's anarchist cell admitted the same thing, on tape.

This wouldn't have been news to Upton Sinclair. While working on Boston, he met with Sacco and Vanzetti's lawyer Fred Moore:

"Alone in a hotel room with Fred, I begged him to tell me the full truth. He then told me that the men were guilty, and he told me in every detail how he had framed a set of alibis for them." (...)

"I faced the most difficult ethical problem of my life at that point. I had come to Boston with the announcement that I was going to write the truth about the case."

Those are excerpts from a cache of Sinclair's letters, serendipitously discovered in a California auction lot in 2005.

"This letter is for yourself alone," Sinclair wrote to his attorney. "Stick it away in your safe, and some time in the far distant future the world may know the real truth about the matter."

Meanwhile, he kept writing his novel, and lied.

As I've complained before, American conservatives have long been instructed to say that those on the left "aren't evil, they're just wrong."

Why can't it be both, and more?

While we had to postpone this year's cruise to next year, it's sure to be a great time on the Mediterranean with Douglas Murray, John O'Sullivan and Michele Bachmann among Mark's special guests. Book yourself a stateroom here. To join in on the collegiality year round, consider joining The Mark Steyn Club, a global community of Mark Steyn readers and listeners.