You'd think if you'd appeared in three movies considered among the greatest of all time, yours would be a household name.

Yet the machinery of celebrity operates on inscrutable Laws, sometimes running counter-clockwise: Sophia Loren, Gina Lollobrigida, W.C. Fields — movie stars all, but how many can name three of their films?

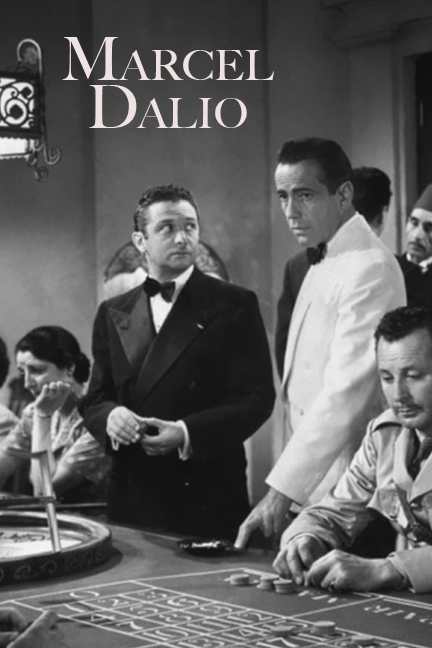

The average (or even above average) person likely wouldn't recognize Marcel Dalio's name, but odds are (no pun intended) they know his face – he's the most familiar croupier in cinema.

And he gets the punchline in one of Casablanca's most famous scenes.

However, there are underrated bits of hilarity in Casablanca (1942) too, such as this exchange between a hoity-toity couple in the club, who insist on having Rick join them at their table, and Carl the waiter, whose jowls jiggle at the very notion:

MAN (to Carl): Perhaps if you told him I ran the second largest banking house in Amsterdam.

CARL: The second largest? That wouldn't impress Rick. The leading banker in Amsterdam is now the pastry chef in our kitchen. (...) And his father is the bell boy.

Why bring that up? Because what differentiates haute coutre from ready-to-wear clothing are details no one but the customer, the designer and the seamstresses will ever be aware of: Stitching so fine it is practically invisible, and boning placed at the exact spot, based upon the client's measurements, where it is most needed. Likewise, what helps make Casablanca great was the brilliant but covert decision to cast actual European refugees as co-stars and extras:

Headliner Paul Henreid, an Austrian Jew, was labelled an enemy of the Nazi party and left England for fear of being deported. S.Z. Sakall (Carl the waiter), also Jewish, left Hungary. Conrad Veidt—cast, ironically, as dastardly SS officer Strasser—was a staunch anti-Nazi who once wrote "Jude" on a race identity card even though he wasn't Jewish (his wife was). Madeleine Lebeau (Yvonne), whose eyes well up with tears during ["La Marseillaise"] fled Paris with her husband Marcel Dalio (Emil the croupier) ahead of the German occupation in 1940.

And a good thing to, because — and this is heart-stopping — the advancing German Nazi army used French movie posters with Dalio's face "as a representative of 'a typical Jew.'"

It didn't help that Dalio's characters in his many French films were mostly sleazy pickpockets and informants, whose Jewishness was taken as read by audiences who were as anti-Semitic as the invading Germans, just a lot lazier about it.

Dalio and his wife, actress Madeleine Lebeau, "waited until the last possible moment and finally, with the sound of artillery clearly audible (...) fled in a borrowed car to Orleans and then, in a freight train, to Bordeaux and finally to Portugal. In Lisbon, they bribed a crooked immigration official and were surreptitiously given two visas for Chile. But on arriving in Mexico City, it was discovered the visas were rank forgeries. Facing deportation, Marcel and Madeleine found themselves making application for political asylum with virtually every country in the western hemisphere. Weeks passed until Canada finally issued them temporary visas, and they left for Montreal."

Film industry friends like Charles Boyer, who'd already escaped to California, arranged for the couple to join them. Dalio arrived in Hollywood with $17 in his pocket, speaking little English. His entire family back in Europe eventually perished in concentration camps.

In America, Dalio was typecast again, except he was no longer "the Jew." He became "the Frenchman," waiters and such "who talked about women and kissed men on both cheeks as cutaway shots showed incredulous American men smirking."

And Casablanca needed some Frenchmen.

They also needed a French woman, so Dalio's wife was hired, too. When she died in 2016 at age 92, Lebeau was eulogized as the last surviving member of the Casablanca cast. You know her, too; she comes in at 1:13.

Sadly, having gone through so much together in such a short time, their marriage wasn't a long one. Dalio served her divorce papers on the Casablanca set, citing "desertion." Whether or not Lebeau's immortal scene was shot before or after that happened, I do not know.

The Nazis had declared Dalio a "typical Jew," but as I alluded to earlier, whether or not a Jew can be a "typical Frenchman" was (and perhaps still is) a matter of some controversy, one explored in his films with Jean Renoir, Grand Illusion (1937) and The Rules of the Game (1939).

Renoir pointedly cast Dalio against type in each films as a wealthy, law-abiding, highly cultured Jew: Rosenthal, the scion of a nouveau riche Jewish banking family in Grand Illusion; and Robert, Marquis de la Chesnaye, a member of the nobility, in The Rules of the Game.

(It's fun to imagine that Emil the croupier was, just a few years earlier, one of those characters, now stuck in Casablanca with the rest of the bankers-turned-pastry-chefs.)

I was blown away by Grand Illusion when I watched it in April, as part of my See Before You Die film festival. Sadly, I failed to find decent subtitled clips from Grand Illusion featuring Dalio for this column, but he can be seen briefly here, as the generous, courageous Rosenthal, excitedly reading the newspaper — and yes, Casablanca lifted this scene.

The Rules of the Game, Renoir's next film, is even more frequently cited on "Greatest Films of All Time" lists — the only one to be included on every Sight & Sound poll since 1952 — so naturally I had to watch it, too.

And... I didn't get it.

Unlike Grand Illusion, which is timeless and universal, The Rules of the Game seems to require considerable knowledge of the French "door-slamming farce" tradition; the intricate upstairs/downstairs social strata being skewed; and the precise state of the world when it was being filmed, in order to be properly appreciated.

I've also been told one has to watch The Rules of the Game repeatedly to fully appreciate it, and I'm certainly willing to do so. In fact, I've found that's true of many movies — except those in which I've discovered layers of meaning and craftsmanship during my fifth or tenth viewings were ones that were already arresting the first time around, such as Citizen Kane and Psycho.

Whereas The Rules of the Game left me quite cold, and critics' identic commentary about it (as I've complained about regarding Grand Illusion) gives the impression of students copying over each other's shoulders during a test.

(We are somberly informed again and again that the "brilliant" "hunting scene" is a haunting montage of war-like cruelty, and while I didn't enjoy seeing a rabbit twitching in its death throws either, I can't help but wonder if any of these essayists had ever fired a gun, wondered where their steaks come from, or been closer to nature than Central Park.)

Dalio was already familiar to me from Grand Illusion, so, while waiting in vain to be impressed, I found myself concentrating on him. His Marquis isn't anywhere as appealing as Rosenthal, but despite the fact that he (and everyone else in the movie) is blithely committing adultery in that "whatever" French fashion, the Marquis is loveably goofy despite, or perhaps because of, his aristocratic station in life.

When he's not bouncing between his wife and his mistress, the Marquis channels his passion into a collection of musical automata.

"There is a scene," writes Roger Ebert, "where he unveils his latest prize, an elaborate calliope, and stands by proudly as it plays a tune while little figures ring bells and chime notes. (...)

"Dalio and Renoir discuss this scene in their conversation [on the Criterion commentary track]. Dalio says he was embarrassed, because it seemed simple to stand proudly beside his toy, yet they had to reshoot for two days. Yes, Renoir says, because the facial expression had to be exact — proud, and a little embarrassed to be so proud, and delighted, but a little shy to reveal it. The finished shot, ending with Robert's face, is a study in complexity, and Renoir says it may be the best shot he ever filmed."

For reasons unknown, the universe seems to have singled out poor Marcel Dalio for attempted oblivion.

When they weren't trying to kill him, or using his face for "WANTED" posters, the Nazis and their collaborators cut all his scenes from the popular 1938 movie The Curtain Rises and reshot them using a non-Jewish actor.

Every print of Grand Illusion was ordered destroyed.

The Rules of the Game received a hostile reception in 1939 — people threw things at the screen and tried to set the theater on fire — and was banned by the wartime French government for "having an undesirable influence over the young."

Adding insult to injury, the original negative was incinerated in an Allied bombing. However, enough materials survived to let two cinephiles painstakingly restore the film to its proper running time and appearance in 1956, under Renoir's supervision — a heroic effort that added to the film's mystique and, I can't help but theorize, has contributed to its "greatest of all time" status.

As for Casablanca, Marcel Dalio's name doesn't even appear on the credits.

In 2015, experimental film essayist Mark Rappaport made a short called I, Dalio, exploring the actor's evolution from "the typical Jew" to "the ultimate Frenchmen" and thereby pondering the very nature of personal identity and public perception, but since the demise of artsy film streaming site Fandor, it is impossible to see.

Intentionally or not, Marcel Dalio's brief scene in Mike Nichols' embarrassingly awful 1970 adaptation of Catch-22 provides a fitting epitaph for a singular actor who survived against all odds, who has not one but three films on any number of "All Time" lists — but whose name is all but forgotten.

While we had to postpone this year's cruise to next year, it's sure to be a great time on the Mediterranean with Douglas Murray, John O'Sullivan and Michele Bachmann among Mark's special guests. Book yourself a stateroom here. To join in on the collegiality year round, consider joining The Mark Steyn Club, a global community of Mark Steyn readers and listeners. Commenting privileges are among the many perks for Mark Steyn Club members, so let Kathy know what you think below!