I was around eight years old during Watergate, and all I knew was that my lunch hour Flintstones were being interrupted by somber men — hunched over, fingers interlaced — grilling each other about "bugs." I was relieved to learn they didn't mean "insects," particularly giant, B-movie ones, but only slightly.

I already worried about hijackings, kidnappings, and muggings (whatever they were). These tiny listening devices that adults were talking, arguing and joking about were added to my list. Were they hidden in our apartment?

Good thing I didn't know then that, for some people, that worry was justified.

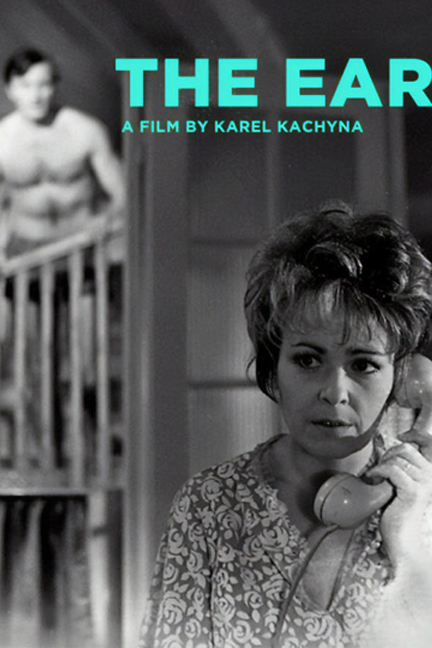

The Ear (1970), directed by Karel Kachyňa, was the last Czech New Wave film made in its home country, before being banned by the Communist Party for the next twenty years.

It's easy to see why. Unlike most Czech New Wave offerings, The Ear wasn't an allegory, satirical fantasia or coy fable, but an impossible-to-misinterpret condemnation of despotic regimes, particularly "the invasion of the political system into the personal space."

That particular slant was why this movie could just as easily have been called Who's Afraid of Virginia Wiretap?

Ludvik and Anna, a married, middle-aged couple, and Anna, return home late at night from a party. Anna is loudly, bitchily drunk, directing her abuse at the quieter, calmer Ludvik. She can't find her keys, although they're both certain they were in her purse when they left. Ludvik fumbles around, while Anna yells at him for being useless, as usual.

Eventually, they make it inside the house. But then the power goes out. So does the phone. Anna notices that the lights are still on in the house across the way, though. Ludvik lights candles and fumbles around, attracting more insults from Anna. On top of everything else, she bellows, he's forgotten their tenth wedding anniversary.

"Do you hear that, Ear?" Anna yells in the general direction of the walls, half in jest. Other people's homes are electronically surveilled by the government, of course, but not their own. Probably.

Ludvik is too preoccupied to pay much attention. Something strange happened at that party, a big, boozy bash for senior Party members like himself — he's the Deputy Minister of Construction — where drunk comrades kept whispering cryptic comments and questions. And, he couldn't help but notice, some men who should have been there, including his boss, never arrived.

Anna looks out the window and sees shadowy men lurking in the back garden.

She and Ludvik try to piece together clues: Had the guest of honor, the Secretary, called her by her first name or not when he gave her flowers? Could the "waiters" have been spies? (They didn't seem to know what salmon was...) And why, when they left the party early, were they driven home via a circuitous route in someone else's car, by a strange driver?

Convinced that his boss has been "purged," and that he'll be next, Ludvik ransacks the house, gathering up old reports — surely this all has to do with that troubled building project he'd worked on — and burning them, throwing the ashes into the toilet.

Anna and Ludvik try to keep their voices down, but inevitably, one of them starts shouting: about their marriage, his career, her affairs, what will happen to their son, and which Party member will be gifted their house when Ludvik gets shipped off who knows where.

Then the doorbell rings.

Many essays about The Ear will tell you what happens after that, and after that. Not me.

You can watch it for yourself, here.

At first, The Ear — with its almost laughable pre-silicon "bugs" and abject, Berlin Wall era setting — seems a mere relic of its time, a curio. The Joke, another Czech film released the previous year, which dramatizes Milan Kundera's famous novel, surely speaks to us more directly. As elucidated frequently on this very site, that novel concerns a Party member condemned for merely making a politically incorrect quip.

What could be more relevant?

I watched both movies the same day, and was surprised to find that I'd forgotten The Joke almost as soon as the credits started rolling, whereas I was impressed enough by The Ear to write about it.

The Ear will inevitably remind you of other movies — Seconds, Night of the Living Dead, Invasion of the Body Snatchers — but definitely not those glossy Hollywood "paranoid" thrillers of the 1960s and 70s, like The Parallax View. This is the East Bloc, not America: nobody looks like Warren Beatty; the Party parties at a centuries-old someplace full of old statues, not the Space Needle.

Out of sheer necessity, let alone rock bottom realism, director Kachyňa expertly builds genuine suspense without committing the cardinal sin of that particular American genre: making the soulless apparatus and fatal outcomes of suffocating government conspiracies seductively glamourous. (I'd be lying if I said that the world of The Manchurian Candidate doesn't look like a kinda cool place to live.)

Only The Conversation (1974) shares The Ear's shabby mise en scene. (I won't soon forget the towers of unwashed dishes in Ludvik and Anna's grace-and-favor home.) Another similarity: While most American paranoid thrillers center on an innocent fellow accidentally snared in a "this is bigger than all of us" web, the protagonists of The Conversation and The Ear were themselves threads of that web who are then transformed, by opaque reversals of fortune, into the spider's prey.

Which is why those who might dismiss The Ear as dated miss the point. Yes, it is very true that we now volunteer to be spied upon through our phones and computers and Amazon Echos. We have traded privacy for convenience and efficiency. I for one know very well that Google, Facebook and Twitter are awful for about a thousand different reasons. I still use them all.

But that's just it: Ludvik and Anna are ordinary, but, as mid-level players in the State's game, they are not innocents.

I'm reminded of the "anti-Big-Government" Tea Party groups that were outraged to discover that the IRS had been "collecting their information" — which they had implicitly made available to that agency the moment they stupidly and cravenly applied for non-profit status, and all the delightful State-sanctioned financial favors such status affords.

And it's worth noting that both Kachyna and his writer Jan Procházka were, like their protagonists, blessed with high-profile Czech communist contacts, who, they presumed, would protect them from the State's wrath when The Ear was released. They were wrong.

We aren't, all of us, in the trap. We are the trap.