There's an oft-quoted story about [Bob] Hope appearing once in England and telling a joke where the punchline was something like, "They went to a motel." The audience howled even though at the time the word "motel" was largely unknown in England. An American journalist who was present asked one of the people who'd laughed if they knew what a motel was. The person said they didn't. The journalist asked them why they'd laughed then. The reply was, "Because we know he's funny and it seemed like the end of the joke." — Mark Evanier

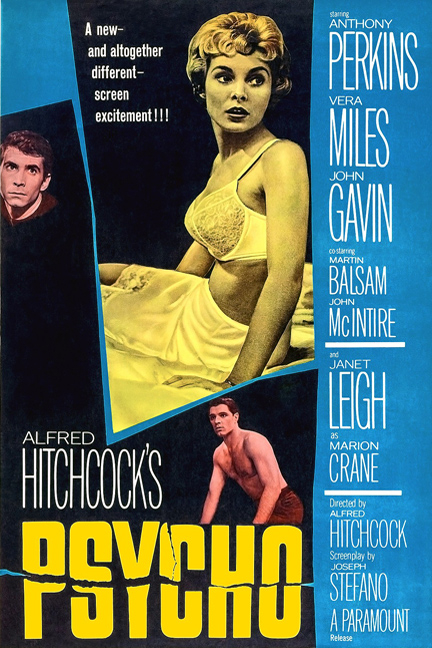

I don't know how many times I've watched Psycho (1960). As a teenager, I even watched it with subtitles, twice: On my Canadian province's mandatory French channel, and then, in a Paris (yes) hotel room. It's the only thing I remember about that entire trip. (I am a very strange person.)

I never found Psycho scary. I feel the same way about The Exorcist (which is basically just The Searchers with vomit) or most of the usual All Time Most Frightening Films.

The closest I get to "scared," every time, is watching Marion's car sink into the swamp, with that stolen $39,300 inside. (I love money.)

Instead, I find Psycho comforting. Its Shaker-plain black and white, and meticulous, even iconic, compositions, contribute to the pleasing sensation that the movie is a miniature, hermetically sealed world. (I collect snow globes.)

Surely these qualities are what have inspired, and then allowed Psycho to withstand — alone among the classics of cinema — everything from a Turner Prize-winning art installation (24 Hour Psycho) and a Don Delillo novel inspired by that, to a regrettable TV series and, of course, Gus Van Sant's self-indulgent frame-by-frame remake. Hell, in recent years, not one, but three movies have been made about the making of this movie. (PS: That was just a short list.)

So: It isn't just me. Close readings of the film abound. And again, more than any other Great Movie, including Hitchcock's purported true masterpiece, Vertigo — something about Psycho infects those who write about it, with mixed results.

Some pedants still peddle long-stale, dime store Freudian stuff about the movie's birds and mirrors and mothers:

Marion starts out wearing white underwear, and later it's black!

The name "Norman" isn't quite "normal"!

Or even: Marion's license plate (almost) spells "ANAL"!!! Please: Hitchcock wasn't that juvenile. (Was he?)

Some of the more elevated observations about Psycho approach the level of poetry, but too often these critics are also, quite possibly, seeing things that not even Hitchcock himself conceived of.

(This is the same Hitchcock who carefully selected, to serve as the peep-hole painting through which Norman spies on Marion, Van Mieris' "Susana and the Elders.")

But maybe that's what poetry, what art, is...

So, in The Moment of Psycho: How Alfred Hitchcock Taught America to Love Murder, David Thomson insists there's a "a lovely moment," when Marion drives away after her strained encounter with the highway patrolman, "in which the strands of highway seem to make a knot behind her."

Really? And if really, then... why? As a subliminal elbow-nudge that Marion's fate is "sealed"? Perhaps not wishing to jeopardize his own cleverness, Thomson declines to elaborate.

Some observations ring less hollow, as when Thomson later compares Norman, flailing his mop in the blood-stained bathroom, to "the sorcerer's apprentice." Or elsewhere, when Raymond Durgant notes in A Long Hard Look at Psycho that, with her short hair flattened by the shower spray, Marion resembles Falconetti's Joan of Arc.)

But again: Why Psycho? Why not obsess over, say, 1955's The Night of the Hunter, another beautiful, black and white, violent pseudo-rural-Gothic semi-fable, directed by another corpulent Englishman — Charles Laughton — who was also trying to say Something (Unflattering) About America?

Because that's what it always seems to come down to. (Note the subtitle of David Thomson's book. PS: He's also an Englishman...) Psycho supposedly revealed, for the first time ever, that Americans are, I dunno, secretly murderers, or at the very least, too-eager accomplices? Easily shocked (or not shocked enough) by the sight of a flushing toilet?

Such theories leave me as cold as Mother's corpse.

True, Hitchcock's latent love-hate for his adopted home are manifest on-screen. Note how frequently his characters scramble all over, and defile in doing so, world famous American monuments: Mount Rushmore (North by Northwest), or the Statue of Liberty and the Hoover Dam (Saboteur.)

But, with Psycho's rotting mansion on the hill, Hitchcock accidentally created a new one of a sort. (Get your model kit today!)

Psycho is often called (again unconvincingly, by the same pretentious scholars) "a black comedy." And certainly, there are sprinkles of Hitchcock's patented drollery. (Mother "isn't quite herself today.")

No, I don't find the movie funny, any more than I find it scary.

Yet, also accidentally, Hitchcock made Bob Hope's punchline whole:

After Psycho, every Englishman, and everyone all over the world, knew what a "motel" was, forever.

If you enjoy Kathy Shaidle's musings about Psycho, Bette Davis, and all-things classic film, in fact, you'll be happy to know you can spend a week at sea with her, Mark Steyn, and a the rest of the star-studded guest list of the Mark Steyn Cruise this fall from Montreal to Boston. Cabins are selling out quickly, but you can still reserve yours here, or by calling 1-800-707-1634.