Weirdly for such a pagan – possibly even accursed — place, Hollywood has always produced movies that take the existence of God as a given.

Merely to fleece the "rubes"? Because the Bible is a bottomless well of conveniently copyright-free material? Regardless of the studios' questionable motives and morality, George Bailey (to cite just one example) prays desperately, an angel gets his wings, and a secular, cinematic Midnight Mass is begotten.

It's one I skip every year: It's a Wonderful Life (or, as I call it, Uncle Billy Must Die!) gives me hives. I'd rather re-watch The Song of Bernadette, the best Catholic movie ever made by two Jews. (Why be surprised? Everybody knows they wrote half the good Christmas songs, too.)

In these and almost every other "religious" Hollywood movie, the spiritual is sacramental, the "outward signs of inward grace" are set helpfully before our eyes: Bailey's homely corporeal guardian angel, or the unavoidably awkward "Virgin-Mary-as-Glinda-the-Good-Witch" in ...Bernadette. Special effects predominate: Moses' parting of the Red Sea is no mere metaphor in The Ten Commandments.

In other words, the supernatural's incursions into human lives is as taken-for-granted as gravity: "This is no dream, this is really happening!", Rosemary hollers.

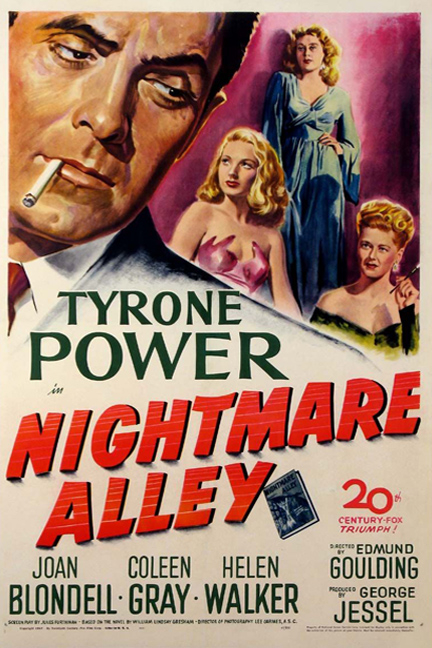

But there are no such outright otherworldly manifestations in 1947's Nightmare Alley, and none would be expected in a gritty film noir of all things, especially one about a heartless carnival con man's further descent into disgrace.

Yet I defy you to name a Hollywood film set in any era past 100 A.D. that features as many characters quoting the Bible and conversing at length about heaven and suchness.

That Nightmare Alley is "God-haunted" is little wonder. The original novel was written by lifelong loser William Lindsay Gresham, whose wife dumped him for her pen-pal C.S. Lewis. (You may have caught their side of the story in Shadowlands.)

Gresham, meanwhile, got on and off at every post-war spiritual bus stop, from AA to Zen. Nothing took. He killed himself in 1962, age 53.

Twentieth Century Fox had grabbed the rights to Nightmare Alley at Tyrone Power's insistence. That impossibly handsome matinee idol wanted to be taken seriously as an actor. Indeed, he played the story's slimy sociopathic protagonist so splendidly that the movie bombed.

Power's Stan Carlisle is a sideshow barker who loves everything about transient, sleazy carnival life. (OK, not that sleazy: while their films were never as glossy as MGM's, Fox simply had to give even this sordid black and white freakshow their trademark "heirloom jewellery" sheen...)

The only ten-in-one attraction Stan can't quite reckon is the geek: A drunk so far gone he bites the heads off live chickens for show, in exchange for "a bottle a day and a dry place to sleep it off."

"How can a guy get so low?" Stan asks Zena (Joan Blondell), the carny's seen-better-days mentalist. Zena and her partner Pete were once vaudeville headliners, thanks to an Enigma-level verbal code they'd perfected to pull off their mind-reading scam. But now Pete's an alcoholic too, so feeble he needs Stan (who never touches the stuff) to help put over the dumbed down version of their old grift:

Alcohol is quickly established as the fifth element in the world of Nightmare Alley, with Stan and the geek serving as Before and Afters of addiction. Pete is the During, although in this scene, the lucid man he used to be briefly surfaces:

And when Stan accidentally kills Pete, it's because he's snuck him a bottle of what turns out to be, not moonshine at all, but the wood alcohol Zena employs in her act.

(In fact, Nightmare Alley is one of the best, most subtle depictions of alcoholism on film. As an early member of Alcoholics Anonymous, Gresham would have been familiar with AA's revolutionary notion, adopted from Jung, that theirs' was a spiritual malady, not just a physical and psychological affliction — a vain attempt to fill one's "God-shaped hole" with booze, or drown out His voice.)

With Pete dead, Stan ingratiates himself further with Zena, convincing her to teach him that precious, proprietary code. Together, they'll revive her old, "big time" act. But once he's mastered it, Stan dumps her for young and lovely Molly (Colleen Gray), rechristens himself "The Great Stanton," and is soon in demand as a high class "spiritualist" at upscale supper clubs (which, either by accident or design, are lit more like Halloween haunted houses — that is, darker than the sideshow).

At one such performance, Stan meets a psychologist whose wealthy clients he plots to bilk as their personal guru. But this lady doctor has tricks of her own up her sleeve...

Getting back to where I started:

Note first that everything predicted by Zena's tarot cards comes true.

But more to the point: Are Stan's psychic powers genuine? When others suggest that, he scoffs that his eerily specific "cold readings" would've worked on any random chump. Yet many scenes suggest otherwise.

Others are impressed by his knowledge of the Bible, and Stan shrugs that off too, as just some nonsense he was forced to swallow back at the orphanage, along with the lousy chow. Yet in that particular scene, Powers' line-reading is either brilliant or inept, because there's a catch in his cocky voice as those words leave his lips. Maybe, for once, Stan is trying to con himself — and faltering.

Stan's "miraculous," and touchingly genuine, conversions are particularly impressive because his converts are so worldly and wealthy — and aren't we told it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of God? It's actually painful to watch Stan unload a spiel about faith and prayer on one newly humbled gentleman, to hear this powerful old millionaire, whose money could never buy him the one thing he wanted most, gingerly yet bravely bare his soul to Stan — while we know that although every word of this exchange is sound and true, only one of them sincerely believes what they're saying. Until...

While toned down a little for the movies, the Great Stanton's ignoble, stomach-churning fate in the finale (can you guess it?) echoes his creator's early, drunken death.

Stan's psychic abilities may or may not be real, but Grisholm predicted his own grim future all too well.

Kathy will be among Mark's special guests on the upcoming Alaskan cruise, setting sail in just over a month. If you'd like to partake in the revelry and review aboard this annual shindig, you can book a cabin for next year's Mediterranean voyage here. Join in on the year-round discussion with a membership to the Mark Steyn Club.