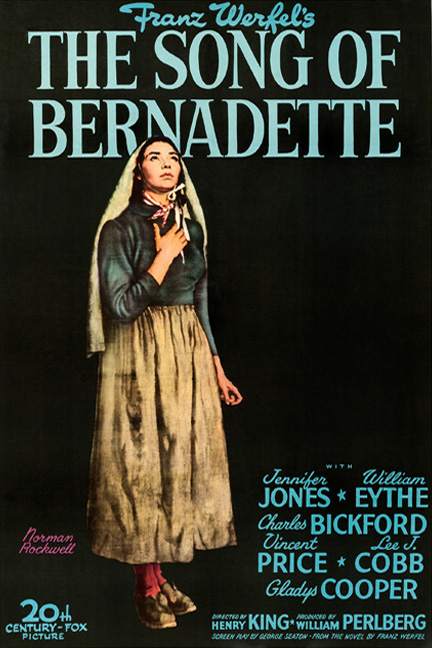

I recently quipped that 1943's The Song of Bernadette was "the best Catholic movie ever made by two Jews." Its admirers insist you don't have to be Catholic to appreciate this ("based on a true") story of Marian visions and miraculous healings, so maybe those unexpectedly ecumenical origins explain why.

But I'm not sure they're right. No one can watch this (or any movie) through another's eyes. The Song of Bernadette must surely be baffling and even annoying to most Jews, Protestants, and, frankly, not a few Catholics, no?

The film was produced by David O. Selznick from the surprise 1941 bestseller by Prague-born Jewish writer-turned-refugee Franz Werfel, who explained his inspiration:

In the last days of June 1940, in flight from our mortal enemies after the collapse of France, we reached the city of Lourdes. (...)

I became acquainted with the wondrous history of the girl Bernadette Soubirous and also with the wondrous facts concerning the healings of Lourdes. One day in my great distress I made a vow. I vowed that if I escaped from this desperate situation and reached the saving shores of America, I would put off all other tasks and sing, as best I could, the song of Bernadette.

Imagine what another Jewish "Franz" from Prague — Werfel's rough contemporary, Kafka — would have written about Lourdes. Perhaps, like Zola before them, Kafka would have satirized its crass commercialism. But maybe one reason Kafka is still widely read and Zola is not can be accidentally ascertained from the latter's boast that, even after he'd witnessed two healings there:

"Were I to see all the sick at Lourdes cured, I would not believe in a miracle."

Then again, Catholics aren't obligated to "believe in" Lourdes, either.

So why should anyone bother with The Song of Bernadette? True, it's exquisitely made, eloquent, and surprisingly amusing in a Capra-esque way:

But it's still an old fashioned black and white movie about something that may or may not have happened in some Old World village in the middle of the 1800s. So who cares?

The next time you find yourself ordered to deny your core beliefs, not to mention the evidence of your senses — to agree (or pretend to) that men can get pregnant or that humans can control the weather or that a fetus is "just a blob of tissue" — else risk ignominy and perpetual penury, you may have your answer...

Jennifer Jones, in her breathtaking breakthrough role, portrays Bernadette Soubirous, a simple, sickly adolescent, uncomplainingly engaged in the quotidian chores common to dirt poor peasant girls everywhere through the ages — in this case, collecting firewood.

Except one day, she sees and hears a luminous "lady" hovering in a grotto.

(Here and in life, Bernadette never claimed she saw the Virgin Mary per se, although the "lady" declared (albeit ungrammatically), "I am the Immaculate Conception." That particular dogma had only recently been proclaimed by the Pope, ex cathedra. This still-largely-misunderstood teaching had certainly not yet trickled down to little Lourdes, let alone into this illiterate child's mind. One is, again, free to make of this what one will.)

When Bernadette returns to the grotto, the "lady" tells her to dig up dirt with her hands and rub it on her face, to the astonishment of witnesses. Later, a spring erupts in that spot. Bernadette is commanded to tell the world that these are healing waters.

Naturally, none of this is well received. Her parents are angry and embarrassed. The neighbours, scandalized. The authorities, both secular and ecclesiastical, warn Bernadette that she risks being locked up at worst and rendered unmarriageable (itself a veritable death sentence) at best. Her already struggling father will be forever unemployable; they'll see to that, too.

Under mounting pressure, Bernadette quietly yet steadfastly sticks by her story, repeating the "lady's" words (by rote, because she doesn't really understand them herself.) She is so guileless, she's not even impatient with these doubters and tormentors. All she's doing is telling the truth. And wouldn't lying be a sin?

This exasperating struggle frays one's nerves as surely as it would in any Hitchcock "wrong man" movie, and it's here that Eve Tushnet's ingenious take comes, somewhat, to our rescue:

The Song of Bernadette follows a classic horror-film structure in order to make a theological point.

Horror movies, especially supernatural ones, often turn on questions of authority. (...)

The point is to show the failure of accepted, modern authorities—science, medicine, government, reason itself. The people who know the truth are the ones least likely to be believed. (...) [F]rom the disbelieved teenagers in A Nightmare on Elm Street to the disbelieved teenager in The Song of Bernadette — authority, in horror, lies with those to whom powerful men do not listen. (...)

The scenes where local officials scheme to prevent worshipers from believing Bernadette are basically from Jaws if the Fourth of July weekend was a new railroad station and the great white shark was our Blessed Mother.

And of course, while Jaws, too, was inspired by actual events, less discussed is that Peter Benchley transposed them onto the plot of Ibsen's 1882 play about a solitary doctor's thwarted attempts to raise the alarm about contaminated water — the very water on which the economy of a spa town entirely depends.

The play's title is An Enemy of the People.

Of course, that's what President Trump calls the mainstream media, but it also happens to be the title of Tommy Robinson's memoir, about his thankless (and worse) efforts to expose the mass rape of teen girls by Muslim "grooming" gangs.

However much we may appreciate them, surely we've also wondered at times why such messengers — however truthful and timely — couldn't also be a bit more... presentable. More worthy.

This question vexes one particular character in The Song of Bernadette. It isn't fair. Why was she chosen: This ignorant nobody from Nowheresville?

This side of heaven, the only "answer" is the corny, comic Catholic one for everything:

It's a mystery.