First published in 1975, it was only when the sixth edition of The New Biographical Dictionary of Film dropped in 2014 that I started hearing it hailed as "the best book on the movies ever written in English;" "...the most influential book ever written about the movies;" and so forth. David Thompson's massive tome had evidently replaced Halliwell's as THE essential thousand-page reference work for the serious film buff, and I was the last to hear.

I hurriedly purchased a copy and installed it as my new "bathroom book." (Much like being appointed the "Lord Privy Seal," this is a higher honor than you might think just from the sound of it...)

Alas, the book didn't retain pride of place much longer than the next roll of toilet paper, because I did what I've been doing with movie books since the age of about 14: I flipped through the "W"s, looking for a particular name — and it wasn't there.

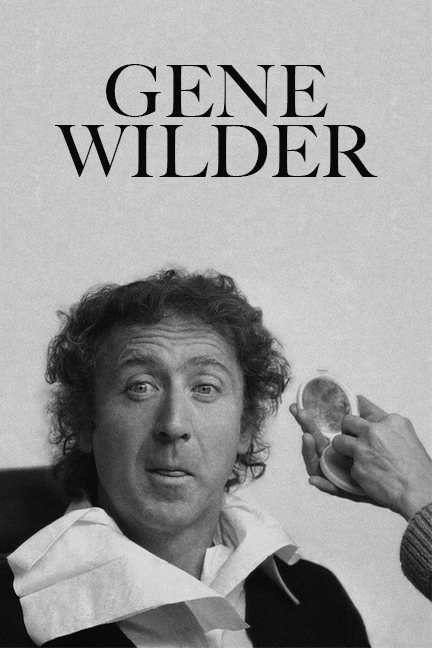

How do you write a "biographical dictionary of film," I wondered then (and now) without including Gene Wilder?

True, Wilder's filmography is slender: fewer than two dozen titles. And too many of those are best forgotten, particularly the ones he unwisely wrote and directed himself. But at the peak of his fame in the 1970s, Gene Wilder was one of the highest paid actors on earth, the star of record-busting blockbusters like Silver Streak and Stir Crazy (both of which ran for a year straight in some theaters, back when such a phenomenon was rare but at least possible.)

More importantly, Wilder was the best thing (sometimes the only good thing) about Mel Brooks' three half-way decent films.

It's true: I don't think Mel Brooks is funny. Fight me.

The very premise of The Producers collapses under the slightest scrutiny: If you've just paid for tickets to a Broadway show called Springtime for Hitler, how dare you be gobsmacked when the opening number is... "Springtime for Hitler"? Blazing Saddles is base and hammy. Young Frankenstein is beautifully shot, but too many of the "jokes" barely meet the definition of the word.

Mel Brooks encourages his actors to mug shamelessly in direct violation of the old comedy rule — illustrated to perfection in Airplane! — that performers should play even the craziest situations dead straight. Wilder is often the sole cast member ignoring Brooks' incompetent direction, tempering these otherwise coarse "comedies" with his eccentric yet strangely sensitive turns. (Note that all three of his collaborations with Brooks feature weirdly touching portrayals of male friendship beneath all the fart jokes.)

Bravely, Wilder dares to take a breath for a beat or two, to be quiet, in these and other films, however zany or absurd:

As a child, Wilder was sternly warned that failure to be quiet might give his invalid mother another heart attack, but the same doctor also advised him, counterintuitively, to "try to make her laugh." He told this story in almost every interview, so it's reasonable to assume it offers an insight into his craft:

At the other end of the spectrum, Wilder was renowned for throwing piercing onscreen fits that make Nicholas Cage look like Cary Cooper — what critic Terry Kelleher called "his usual 'love me, I'm having a panic attack' mode":

That Gene Wilder wasn't nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for Blazing Saddles is an eternal disgrace — note his subtle, ingenious lapse into Henry Fonda's voice at the words "six-year-old kid," below, effortlessly evoking "the Hollywood Western" in a couple of seconds — which is better than ham-fisted Brooks manages to do throughout the remaining 90 minutes:

Gene Wilder is most fondly remembered for playing Willy Wonka, of course. He only agreed to do the film if the director would let him perform that freaky limp/somersault bit in his first scene. Wilder felt, rightly, that that bit of business would set the tone for the whole film, leaving viewers on edge about what was to come.

Now that "dark" films are everywhere (thanks to the so totally "over" Tim Burton and his many imitators) it's easy to forget how twisted Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory is, and that it promptly bombed. The uneasy blend of that trippy late Sixties colour palette with the movie's cruelty and "Edward Gorey" sensibility left many confused and turned off.

But the movie aired regularly on television, (in Ireland, it's practically the national religion,) and thus found its massive audience:

"Vast numbers of Generation X-ers learned all their moral lessons from a single source: the 1971 film version of Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory," wrote Jeff Gordinier in a book about that particular demographic cohort.

"I don't think it's going out on a limb to suggest that repeated absorption of these lessons — it's wrong to sell out, it's wrong to want to be the centre of attention, it's wrong to be too grasping and transparent in your ambitions — made a deep and lasting imprint on the Generation X sensibility."

Aware of his place in the hearts of so many, Wilder — already wilted by cancer — retreated from public life when he was diagnosed with Alzheimer's. His family explained after his death in 2016 that "Wilder did not want to disappoint 'the countless young children that would smile or call out to him, "There's Willy Wonka" or expose them to the cruel realities of the disease. He simply couldn't bear the idea of one less smile in the world."

He was good at keeping secrets. Only in his 2005 autobiography did Wilder shatter the widespread illusions that he and frequent collaborator Richard Pryor were the best of friends off screen, or that his marriage to Gilda Radner had been an idyll. In truth, both comedians — by then deceased — had often been profoundly neurotic, mercurial and selfish, with drug use making Pryor particularly incorrigible; he frequently, foully, insulted Wilder in the press, but his partner in comedy never responded in kind.

Stoically, graciously maintaining those illusions for so long (especially while setting up Gilda's Clubs for women with ovarian cancer, and campaigning successfully for improved early detection methods) was Wilder's longest running performance.

And one that was widely ignored: After his own death, touching tweets to the tune of "He's been reunited with Pryor and Gilda!" were commonplace. I doubt such a prospect was the man's idea of heaven.

Oh well. Who can blame so many people for wanting to live in "a world of pure imagination," especially when Gene Wilder himself had made it such a magical place?

Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think in the comments. If you aren't yet a member but wish to join in on the fun, you can sign up or get a loved one a gift membership here. To meet your fellow Club members in person, consider joining our third annual Mark Steyn Cruise next October, featuring Conrad Black, Michele Bachmann and John O'Sullivan, among other distinguished special guests.