To say that many of us look forward to TCM's annual year-end "In Memoriam" video seems shamefully morbid. But these short films are made with such care that we can't help ourselves.

Only when I saw the 2019 edition this week did I learn of the passing of two actresses whose names aren't well-known even to some film buffs, but whose faces, in singular roles, turned them into pop culture icons.

That they both died the same year is a bizarre coincidence, because their most famous films came out within two years of each other. These two movies were often compared and contrasted: Both are cult, "mad doctor" horror films — one regarded as high art, the other, sub-par exploitation — and both, while made by men, explore the topic of beauty as a woman's greatest (and most fragile) asset.

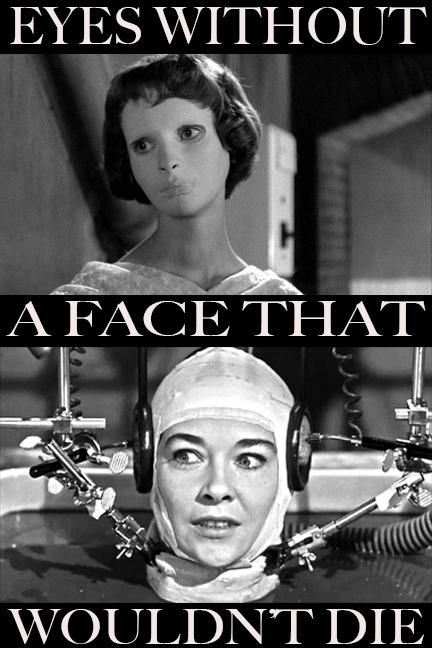

First, the late Edith Scob, whose homely name is incongruous with her ethereal, silent star turn in the French film Eyes Without a Face (Les yeux sans visage).

She plays Christiane, the daughter of a Parisian surgeon whose reckless driving led to the car accident that caused her disfigurement. Guiltily obsessed with restoring her face, he murders young women and performs unsuccessful (and still almost-unwatchable) face transplants.

The mask Scob wears throughout was molded from her own face, making it at once "real" yet utterly artificial, a reminder that beauty is, cruelly, a matter of millimeters, adjudicated by the micro-messages that eyes whisper to brains in pitiless nanoseconds.

Christiane's face is uncanny, but not grotesque. Facial trauma may be, as one scholar has argued, a distinctly French preoccupation:

"From Alexandre Dumas' Man in the Iron Mask, Leroux's Phantom of the Opera, and Victor Hugo's Laughing Man, to the post-WWI obsession with the gueules cassées (the facial mutilees of trench warfare) (...) it has been a theme so significant as to amount to a national obsession."

Now contrast that with another national obsession: The Unknown Woman of the Seine, a 19th century Parisian drowning victim whose smooth, flawless death mask with its enigmatic smile inspired Camus, Rilke and Nabokov, decorated many a French home — and is the face you peer down at when learning CPR with a mannequin.

And since Eyes Without a Face is about a woman, its French creators can't bring themselves to display the marred visage under Christiane's own (living) death mask. Gory depictions of surgery are one thing but expecting audiences to stare at an ugly woman onscreen for almost two hours is a taboo they know better than to violate.

Director Joseph Green must have intuited this as well. (Note that the vicissitudes of production and distribution in those days mean it is impossible, contrary to what you might think, for him to have seen Eyes Without a Face, or vis versa. There was simply something in the air: Movies with similar themes made during this era include Germany's The Head, They Saved Hitler's Brain, The Thing That Couldn't Die, and the Mexican production The Living Head.)

So for most of The Brain That Wouldn't Die, viewers are treated to the gorgeous visage of Virginia Leith, who also died this year. Blessed as well with a husky voice, Leith (that rare woman who looks lovelier without her hair, in this case, with her head swaddled) plays Jan, the nurse-fiancé of an egomaniacal surgeon who, like his counterpart in Eyes Without a Face, is responsible for the car accident that (in this case) decapitates his beloved. He takes Jan's head to his secret lab, revives it and keeps it alive, then searches sleazy strip clubs for the perfect body on which to attach it.

Jan is less than thrilled by this arrangement, declaiming semi-Shakespearean condemnations until Doc briefly bandages her mouth shut. Leith's strong performance is especially impressive when you consider that she must have been kneeling for hours under the table through which her head pokes.

The Brain That Wouldn't Die is a fable worthy of Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton or Margaret Atwood — like Eyes Without a Face, an accidental proto-feminist fairy tale; "It's hard to think of other films from its era," writes Bryant Frazer, "that are so cognizant (not to mention sharply critical) of the male gaze, institutionalized sexism, and the moral bankruptcy of the pick-up artist."

It should shame feminist artists that so many of the most accurate cinematic explorations of the female experience have been made by men: Carrie (1976), The Wasp Woman (1959) and The Craft (1996); Mildred Pierce (1945) and Baby Face (1933); any number of Bette Davis films, particularly 1950's All About Eve, whose writer/director Joseph L. Mankiewicz declared, "Male behavior is so elementary. All About Adam could be done as a short."

Well, maybe: Steve Martin's 1983 smart spoof of these films and their ilk, The Man With Two Brains, frankly wrestles with the adjacent male dilemma:

Do I choose the crazy sexy beautiful woman who'll ultimately ruin my life, or the plain, smart, kind one who gets my jokes?

These themes continued to inspire filmmakers: witness the Re-Animator series, and Almodóvar's The Skin I Live In (2011). But I doubt most of these modern movies will enjoy the longevity of either the critically acclaimed masterpiece Eyes Without a Face or "so bad it's good" The Brain That Wouldn't Die. But all those adjectives are lazily overused, and in the latter's case, unfairly so.

Yes, ...Brain... IS a "terrible" movie, when judged by traditional aesthetic criteria. Yet, like Jan's severed head, it lives improbably on, an inadvertent meditation on beauty and identity, the battle of the sexes, ethics and autonomy, life and death.

Messages aside, both movies are a testament to the power of a single, still simple cinematic image to withstand the turnover of time and tastes.

"We had faces then," spits faded film queen Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard. If only she'd stayed out of prison long enough to see Eyes Without a Face and The Brain That Wouldn't Die.

Eyes Without a Face streams on Amazon Prime. YouTube offers poor quality public domain prints of The Brain That Wouldn't Die, but the definitive high-def Blu-ray version, with audio commentary, is available from Shout Factory.

~Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think in the comments. If you aren't yet a member but wish to join in on the fun, you can sign up or get a loved one a gift membership here. To meet your fellow Club members in person, consider joining our third annual Mark Steyn Cruise next October, featuring Conrad Black, Michele Bachmann and John O'Sullivan, among other distinguished special guests.