When Douglas Sirk left Hollywood he was at the zenith of his career, twenty years after he'd arrived there as a refugee from Nazi Germany, unsure if he'd ever make another movie. He had just made his most successful picture, based on what was probably the most controversial topic in America at the time. Maybe he understood that it's always best to leave when you're at the top, or maybe he was just tired.

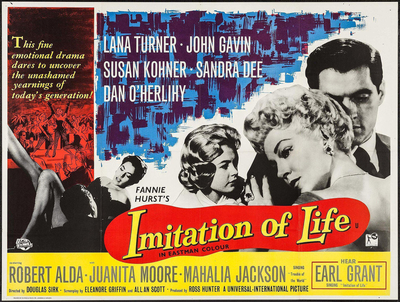

Imitation of Life was an update of a 1934 film starring Claudette Colbert and Louise Beavers – a drama about miscegenation and racism and the colour caste system that was no less controversial when producer Ross Hunter decided to remake it – as a musical. Thankfully, by the time Sirk started filming, it was a melodrama again, and one starring Lana Turner, just after her daughter Cheryl Crane had been on trial for running a kitchen knife through Turner's boyfriend, a mobbed-up gigolo thug named Johnny Stompanato.

Based on a novel by Fanny Hurst, the original film directed by John M. Stahl had Colbert's Bea create a culinary empire based on a pancake recipe passed down through the family of Delilah (Beavers), her African-American maid. Both women prosper, but Bea's happiness is threatened when her daughter falls in love with the man she wants to marry. James M. Cain's 1941 novel Mildred Pierce – later made into a movie with Joan Crawford and a miniseries starring Kate Winslet – is basically a hardboiled rewrite of Hurst's story, excising the crucial secondary plot involving Delilah and her daughter, a young woman striving to pass for white.

Sirk's film updates the story by turning Bea into Turner's Lora, a struggling actress who becomes a Broadway sensation, largely thanks to her maid Annie taking on the work of raising her daughter and keeping her house. Sirk's film also makes the story of Annie and her daughter ultimately more important than the love triangle between Lora, her daughter Susie (Sandra Dee) and the reliably stolid John Gavin.

The film begins with a credit sequence typical of the films Sirk made with Ross Hunter – jewels cascade into a glittering pile against a black background; on the soundtrack, a tragic, minor key fanfare by composer Frank Skinner segues into Sammy Fain and Paul Francis Webster theme song, sung by Earl Grant doing his best Nat King Cole.

On a busy weekend in Coney Island in 1947 the camera picks out Turner's legs in the thronging crowd – she's trying to find her daughter, who's gone missing, and gets help from Gavin's Steve, a struggling street photographer trying to do the Cartier-Bresson thing with his Leica. Lora's daughter has found a playmate in Sarah Jane, the daughter of Annie, out-of-work and homeless, trying to escape their desperate situation with a day at the beach. The two women bond, and when Lora offers Annie and Sarah Jane a place to sleep for the night in her coldwater flat, Annie makes herself so useful that Lora agrees to let them stay, Annie working as maid and cook for room and board until things look up for both of them.

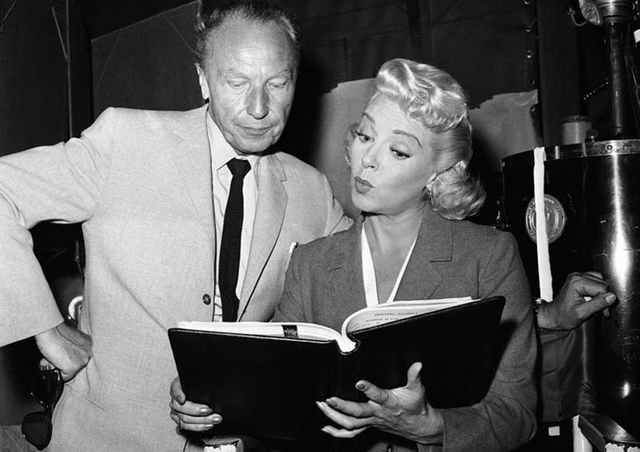

Make no mistake – Lana Turner was the star of the film, the sort of just-past-her-prime screen goddess that Hunter loved to work with. But the film revolves completely around Juanita Moore as Annie, so much that Hunter told Moore before filming began that the picture's success hinged on her performance.

It was a lot of pressure to put on an actress with a long but thin resumé on film before she took the role. Born in Mississippi but raised in Los Angeles after her family joined the Great Migration when she was little, Moore began her career onstage as a dancer at the famous Cotton Club and in "black and tan" night spots where black entertainers performed in front of white audiences. Her filmography began in the late '30s – a long list of mostly uncredited roles as a nightclub patron or dancer, or as a "dressed up freed slave" (Belle Starr, 1941), "native woman" (Tarzan's Peril, 1951) or "tribal woman" (Something of Value, 1957).

Moore was, however, a significant player in Los Angeles' black theatre community – hardly unknown, if you knew where to look. Casting the part of Annie, Hunter apparently moved from Ethel Waters to Pearl Bailey to Marian Anderson and finally Mahalia Jackson, who dutifully auditioned, but told the producer that while she really wasn't an actress, he should look at her friend Juanita Moore.

Or at least that's one of his stories. In another one Hunter said that he saw Moore sitting on a bench waiting for a bus. Moore herself said that she got the role thanks to Joel Fluellen, a mainstay in L.A.'s black theatre scene, who would play the minister in the final, tragic, operatic scene of Imitation of Life. In the end it doesn't matter much; everyone behind the scenes from Hunter to Sirk down knew that Moore's Annie was the real star of the movie.

"I'm going to stick my neck out for you," Hunter told Moore. "If you're no good, I'm finished at Universal."

The story of Turner's Lora, her daughter and Steve is classic showbiz melodrama, and you get the feeling that Sirk could have directed it in his sleep, since it plays out onscreen like some kind of lavishly costumed ritual – a cargo cult retelling of All About Eve, Stage Door, 42nd Street, A Star is Born and Twentieth Century, recalled from memory.

But the story of Juanita Moore's Annie and her daughter Sarah Jane is the real dramatic muscle and bone of the picture, and Sirk invests it with all of his skill to let it play out onscreen with an emotional power that he rarely matched in his other movies.

At no point in any description I've read or heard about Sirk as a director does anyone talk about emotions. Distant and intellectual, he's recalled as a caricature Teuton, remembered more for his manners than his warmth. In this light, it's no surprise that there's a sometimes clinical perspective on the foibles, failings and tragedies of characters in his melodramas – a coolness that's at odds with the overcooked emotions inherent in the genre.

But something had happened to Douglas Sirk, both in his past and recently, that might explain how a dam broke with Imitation of Life, and maybe even why he decided to make an exit from moviemaking.

The year before he directed Imitation of Life, Sirk had made A Time to Love and a Time to Die, a war movie without battle scenes, starring John Gavin as a German soldier troubled by the war crimes he sees on the Russian front. Shot on location in Berlin and Bavaria, it was the first time Sirk had worked in Germany since he left the country in the '30s.

Sirk's only son Klaus was born in 1925, the product of his first marriage to the actress Lydia Brinken. Brinken became an ardent Nazi, joining the party before Hitler's 1933 chancellorship, and thanks to her connections she was able to get a court order preventing Sirk from seeing his son, due to his second marriage to singer/actress Hilde Jary, who was Jewish.

Brinken got their son roles in films, usually playing the boyish Aryan ideal in propaganda cinema, and Sirk was only able to see his son onscreen. Hilde Sirk managed to escape Germany in 1936, though her husband's passport was confiscated as part of an effort by Joseph Goebbels' propaganda ministry to retain Sirk as a director of pro-Nazi cinema.

Sirk got out of the country a year later and arrived in Hollywood in 1939, where he would struggle to get work – at one point he owned a chicken farm, later he grew avocados and alfalfa – before getting his break directing Hitler's Madman a sub-B propaganda picture about the assassination of SS official and Nazi war criminal Reinhard Heydrich, played by John Carradine.

Klaus Sirk was drafted into the army in 1942, and was killed in the Ukraine in May of 1944. Sirk briefly returned to Germany after the war to fruitlessly search for his son.

It's tempting to imagine – though Sirk himself would never give you the satisfaction of knowing –that this estrangement, longing and loss informed the scenes in the second half of Imitation of Life, where Sarah Jane insists on trying to pass for white, running away from her mother and finally demanding that she leave her life, telling Annie not to talk to her again if they meet on the street.

The grown-up Sarah Jane was played by Susan Kohner, the daughter of Lupita Tovar – a Mexican actress, famous in her homeland, who played Mina in Universal's Spanish version of Dracula, filmed on the same sets at the same time as Tod Browning's 1931 horror classic. Her father was Paul Kohner, a Czech Jew who became a major Hollywood agent, representing not just his daughter but Sirk, Turner, Moore and Imitation of Life cinematographer Russell Metty.

Kohner's performance was nearly as crucial as Moore's, since the struggle between Annie and her daughter becomes the dramatic engine of the film's second half. Her ambiguous racial identity defines her from the first scene, when Lora assumes that Annie is her nanny and not her mother, and when the two of them come to stay with Lora and Susie, Sarah Jane starts a scene when she rejects Susie's gift of a black doll.

Later, when Annie is telling the nativity story to the girls, Sarah Jane asks if Jesus is black or white, insisting that he's "white...like me." Her attempts to pass – and her mother's struggle to get her to accept herself – become more desperate as she gets older. By the time Sarah Jane is an attractive young woman, her rebellion is full of anger and resentment; asked by Annie to bring a tray of canapés in to Lora and some guests, she puts the tray on her head and adopts a broad plantation drawl, an acid impersonation of the dutiful coloured servant in so many movies.

You're forced to compare the daughters; Sandra Dee's Susie is cloying and a bit spoiled, calling for her mother's attention by trying to be as picture perfect as you'd imagine the daughter of a glamorous Broadway star. Sarah Jane, however, is a petulant brat next to the saintly, self-sacrificing Annie, who has had to divide her energies as a mother by taking on the role with Susie as well as her own child.

It would be easy to dislike Sarah Jane if it weren't for the unpleasant fact that her anger is justified. When it's pointed out that she's been given every opportunity available, it's obvious that those opportunities were nothing like those given to Susie, raised in the same house. When her mother asks her why she won't go to a black college or attend church parties, Sarah Jane rages that all she'll meet are the children of railway porters and other servants. On the surface it sounds like a churlish rejection of black society and generations of strivers, but it shows that she's unwilling to accept the lie behind the premise of "separate but equal."

Sarah Jane's motives for wanting to pass might be selfish and caused by a yoke of shame forced on her, but they're only shocking in that she acts on them just a few years before they'd be assumed by most young black Americans.

She manages to get a white boyfriend, a townie played by Troy Donahue who turns out to be a vicious racist when he discovers her secret. He asks who her mother is and uses the "n-word," before beating her to the pavement in an alleyway. Younger viewers – if there are any for '50s melodrama these days – will be shocked, perhaps even tearful when the budding teen matinee idol spits out the word.

They should be – it's a shocking word, as much in 1959 as today, and perhaps even more when it wasn't generously larding the lyrics of songs on the Top 40 and elsewhere. It's the key to discerning the difference between a racist movie and a movie about racism, though I fear that's a distinction we're less able to make with each week.

Sarah Jane's rebellion is reasonable, even if it manifests itself by harming both herself and her mother, which is pretty much the definition of tragedy. You have to contrast it with Annie, who has a relationship with Lora – her friend and her employer – that's far more amiable on the surface. During one of their habitual late night chats, Lora is shocked to learn that Annie has many friends, and a broad social network based around her church and several lodges. Why didn't she know that?

"Miss Lora," Annie replies with a chastening frankness, "you never asked."

In her bid to escape – her mother, her life's arbitrary limitations and herself – Sarah Jane decides to use the thing people can see (her looks) to cover up what they can't (her race). At first this leads her to Harry's, a dingy basement showbar in Manhattan where she dresses in fishnets and a bodice to gyrate to a vaguely burlesque ditty (Frederick Herbert and Arnold Schwarzwald's "Empty Arms") full of "oopsie" double entendre, clearly recorded by someone with a richer, more adult voice than Kohner. (In fact Jo-Ann Greer, who provided the same services for Rita Hayworth, Gloria Grahame and Esther Williams.)

After Annie drags her out of Harry's, Sarah Jane runs further and faster, ending up at L.A.'s Moulin Rouge club, where she lands a job as a chorus girl in one of the club's Vegas-esque stage shows. Filmed in the real club, with a currently-running show and its cast, Sirk's camera gives us a giddy glimpse of a swanky night club stage show during the last moments when adults were still in charge of culture.

Annie tracks Sarah Jane down to her motel but instead of taking her home promises that she'll leave her alone, and that this was her chance to get a last look at her baby. When a redhead buddy from the chorus shows up, Annie pretends to be Sarah Jane's childhood nanny, paying a quick visit while passing through town. After a quick, tearful hug, Sarah Jane mouths the word "momma" before pushing Annie from her life.

In Fanny Hurst's novel, Delilah's daughter dreams of working in white restaurants, achieves her dream of passing and marries a white man before escaping America and her identity. In the 1934 movie as well as Sirk's version Delilah/Annie's daughter doesn't get away so cleanly.

Annie returns home – or to her room in Lora's home – with a broken heart. We have to endure trying scenes where Dee's Susie prattles to the ailing Annie about her crush on Steve, oblivious to the woman's real suffering. The film's title gets an offhanded explanation when Susie discovers Steve's real feelings for her mother, leading to a confrontation that it's hard to give a damn about, knowing what we do about what's just happened with Annie and Sarah Jane.

Turner – who never looks less than fabulous in the picture, even as a poor widow, in a wardrobe that cost Hunter and Universal over a million dollars – arches her eyebrows and looks noble as she promises he daughter that she'll give up Steve if that will help.

"Oh mama, stop acting," Dee says, her best line in the film, and one as chastening as Annie's.

You can also assume that passing for another race in denial of your own is an imitation of life; I doubt that Sirk would have argued the interpretation.

Annie dies – a good death, thanks to Moore's incredible performance and the Christian standard of a coherent, dignified passing, attended by friends, family and clergy, bequests issued and affairs in order. But when her end comes it's nonetheless heartbreaking, due largely to Turner's truly palpable grief, by no means an imitation of real emotion.

But that's nothing compared to what comes next. Annie had saved up for years to afford a lavish funeral, with white horses and a black carriage, a band and a procession of mourners. Sirk and Hunter bring it to the next level with none other than Mahalia Jackson herself, singing "Trouble of the World" over Annie's coffin. Turner was nearly hysterical during filming, rushing from the set and weeping in her trailer. Apparently the actress had trouble distinguishing an imitation from the real thing.

The grief explodes out of the screen, defying anyone who has a dry eye, and as Annie's coffin is carried out of the church and into the hearse, Sarah Jane returns, forcing her way through the crowds in the street and flinging herself onto her mother's coffin. This isn't stage grief – Lora's specialty – but very near the real thing, a messy, painful moment where Sarah Jane wails that she killed her mother, with the lacerating certainty that she really did.

It's a stunning, even overpowering ending, made more so by the way that it grows out of what started out as a mannered melodrama that only hinted at its emotional undercurrents. Sirk himself never described his achievement in anything less than technical terms – an attempt to convey the reactions he'd witnessed to Jackson's performance. "I have no talent for sentimentality," he said later. "Perhaps I don't recognize it."

Imitation of Life was a hit – Universal's biggest picture to date. The reviews weren't so kind; Bosley Crowther of the New York Times called it "detergent drama" and a "sob story". John McCarten in The New Yorker dismissed the whole cast, saying "I can't find much to say in favor of any of them." But melodrama in general – and Sirk in particular – wouldn't get much leeway in quality media like the Times and the New Yorker for years, until younger filmmakers and a new generation of critics rebelled against these rote dismissals.

Juanita Moore died in 2014, on New Year's Day. Along with Susan Kohner, she received Oscar and Golden Globe Best Supporting Actress nominations for Imitation of Life (Kohner won the Golden Globe) but waited two years before being offered another movie role. Lana Turner had a comeback in the '60s with films like Madame X and Portrait in Black (both produced by Ross Hunter) and died in 1995.

Sandra Dee's life after Imitation of Life was increasingly miserable, starting with her marriage to singer Bobby Darrin in 1960. She died in 2005 after years of struggle with alcohol and anorexia. Susan Kohner is still alive – she left show business in 1964 and married John Weitz, a novelist and fashion designer. Her sons Paul and Chris co-directed American Pie, before going on to write or direct About a Boy, Little Fockers, The Golden Compass, The Twilight Saga: New Moon and Rogue: A Star Wars Story. (In Hollywood, nepotism spans generations.)

Mahalia Jackson had not one but two funerals, in Chicago and New Orleans, attended by thousands, including Coretta Scott King, Sammy Davis Jr., Dick Gregory, Lou Rawls and Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley. Aretha Franklin sang at her Chicago funeral.

Douglas and Hilde Sirk left Hollywood after Imitation of Life premiered, moving to Lugano, Switzerland. He never made another picture, but he began teaching at a film school in Munich in the '70s, after his reputation had been reassessed by a new generation of filmmakers and critics. He died in 1987.

Just before Diana Ross left the Supremes she recorded "I'm Livin' In Shame," a 1969 hit single that's very nearly a three-minute distillation of Imitation of Life – minus the passing. Assuming the role of Sarah Jane, Ross sings about her mama, who wore a sloppy dress and ate from the pot without a fork or plate, a woman her uptown friends, husband and children have never met.

There's no reason to think that the song, by the same team of Motown writers who wrote "Love Child" at the same time, was inspired by Sirk's film except for the refrain "Mama, Mama, Mama can you hear me?" directly quoting Kohner's griefstruck Sarah Jane at the funeral. It's possible that, ten years after the release of Imitation of Life, class was more of an issue to black Americans than trying to pass as white. If so, that's at least something like progress.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.