John "Paddy" Hemingway, the last surviving pilot who flew in the Battle of Britain, died in March of this year. He was 105. Hemingway was forced to bail out of his aircraft four times – three times in England and a fourth over enemy territory in Italy, where locals helped him get back to Allied lines. He said that his "biggest regret was the loss of friends, in particular that of Richard 'Dickie' Lee in August 1940."

The last living witnesses to World War Two are leaving us and taking a shared memory of its history with them. If you believe this millennial representative, young people should know as little about the conflict as possible as it's harmful to their mental health. And like all history beyond the visible horizon of the present day, what most people will know about that war by the time its centenary rolls around will come almost entirely from movies and television.

(There are books, of course, but I'm not imagining the world will be less post-literate in fifteen years.)

The best recent depictions of the war – my subjective list includes Band of Brothers, The Pacific, Saving Private Ryan, Dunkirk, Das Boot, Greyhound and Letters from Iwo Jima – were mostly made with veterans advising on historical accuracy and mostly being heard. This wasn't always the case: for at least two decades following the war, when veterans were still thick on the ground, historical accuracy was frequently sacrificed in the interest of adventure, drama, comedy or romance.

(My subjective list includes Kelly's Heroes, The Dirty Dozen, The Guns of Navarone, D-Day The Sixth of June, Where Eagles Dare, Operation Petticoat, From Here to Eternity and Von Ryan's Express. Not that these aren't entertaining, enjoyable films; they just shouldn't be considered history.)

If there was a turning point – a film that struggled and mostly succeeded in telling a plausibly accurate story about the war to audiences likely to contain not just veterans but civilians with lived memories – it was probably Guy Hamilton's Battle of Britain, released in 1969, barely thirty years after the event it commemorates.

While in pre-production for the film, 007 producer Harry Saltzman and his co-producer (and veteran RAF pilot) Benjamin Fisz realized that their American backers at MGM were nervous about making a film about something Americans knew little about. This led to The Battle for the Battle of Britain, a short TV documentary about the film and the event that it was based on, hosted and narrated by one of the film's stars, Michael Caine.

Included with the 2005 collector's edition DVD of Hamilton's film, The Battle for the Battle of Britain begins with a series of "man on the street" interviews conducted outside the American embassy in London. Older interview subjects talk vaguely about how they'd admired the British for standing alone against Nazi Germany at the time; younger ones almost unanimously admit that they don't' know anything about it. One woman states that she doesn't wish to give an opinion since she works for the embassy. At the time these interviews were made the average age of a British pilot who fought in the battle and survived would have been around fifty, as the vast majority of the young men who flew to defend England in the summer of 1940 were on either side or twenty.

Making Battle of Britain felt like a duty in 1969; it attracted a cast of big stars who were willing to work for scale just to be involved, but that didn't stop the film from going massively over schedule and over budget. Historical accuracy was so important that Saltzman and Lisz ended up collecting what became the world's 35th largest air force, rebuilding wrecked airframes and making planes that had sat on concrete plinths outside museums and airfields flyable again.

The film begins with the fall of France in the spring of 1940, and British pilots and air crew struggling to get back in the air ahead of the rapidly approaching German army. We meet the three RAF squadron leaders who will be at the centre of the action: Caine's Canfield, Robert Shaw as the curt, intense "Skipper", and Colin Harvey (Christopher Plummer), a Canadian married to Maggie (Susannah York), an officer in the Women's Auxiliary Air Force.

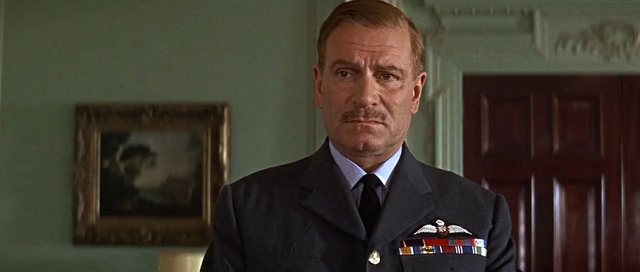

Back across the channel we meet Sir Laurence Olivier as Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, the head of Fighter Command and the man who will lead the English in the air battle to come. Blunt and charmless, Dowding had the unenviable task of telling Sir Winston Churchill, only just appointed Prime Minister, that he doesn't support his promise to send more fighter squadrons across the Channel to aid the French as they would be squandered in a lost cause and, in any case, he needs every plane and pilot he has to fight the German invasion that's doubtless coming.

Dunkirk falls and the British ambassador to Switzerland (Sir Ralph Richardson) is visited by his German counterpart (Curd Jürgens), who arrogantly demands that Britain admit defeat and submit to terms that will allow Germany free rein over everything in Europe they've already conquered. Richardson tells him that since Der Fuhrer's guarantees have so far proved worthless he should, in essence, get stuffed, then complains to his wife that he did the unpardonable and lost his temper.

While the credits roll over a military march we get our first look at the Luftwaffe that will be facing Dowding, Canfield, "Skipper" and Harvey; airfield after airfield lined with Messerschmidt Bf-109 fighters, Heinkel He-111 bombers and their smartly turned out aircrews as they're inspected by Erhard Milch (Dietrich Frauboes), second in command to Hermann Göring, and Field Marschall Albert Kesselring (Peter Hager), commander of one of the Luftwaffe divisions tasked with sweeping the RAF from the sky.

It's meant to be impressive and sinister, though by 1969 movies were in the habit of humanizing our onetime enemies and Milch begs off further inspections, pleading boredom and leaving Kesselring to finish the job. This gives him a chance to visit a squadron of fighter pilots based in a seaside hotel with a view across the channel to England. They're led by Majors Falke (Manfred Reddemann) and Föhn (Paul Neuhaus) – two dashing aces responsible for the squadron's high morale. Falke is clearly based on Adolf Galland, the leading Luftwaffe ace of the war and Föhn, by implication, is meant to be his friend and fellow ace Werner Mölders.

Galland, along with Hitler's architect and Minister of Armaments Albert Speer, frequently appears in World War Two documentaries as a reasonable eyewitness explaining the German side. Unlike Speer he escaped war crimes tribunals and was putatively "denazified", left Europe to advise Peron's Argentine air force and returned to Germany to start an aircraft consultancy firm. He was hired as an advisor on Battle of Britain but frequently clashed with Hamilton and the producers, insisting on watering down the "Naziness" of the film's Luftwaffe personnel. (Mölders died in 1941 when the plane flying him from Crimea to Germany for a funeral crashed in Poland.)

On the British side the handful of flyers we meet are meant to stand in for the just under 3,000 aircrew who flew against the Luftwaffe. Edward Fox plays Archie, who's typical of the upper middle-class pilot officers who made up much of the peacetime RAF, inheritors of the mantle of Biggles, the fictional World War One ace and hero of W.E Johns' wildly successful adventure novels. Forced to bail out of his plane, he parachutes onto a cold frame in the garden of a suburban home. "Thanks awfully, old chap," he says when a young boy in his school uniform runs out of the house to offer him a cigarette.

Ian McShane plays Andy Moore, one of the working-class non-commissioned pilot sergeants added to the ranks of Fighter Command as Dowding became desperate for men to fill the cockpits of his planes. He's sent his family out of London to escape the expected German bomber raids but they return when they find the countryside dull. Coming home on leave just as the first air raids of the Blitz have started, he finds them in a rest centre after they've been evacuated from their street by an unexploded bomb.

Called away to help rescue victims trapped in the rubble, Andy returns to find the rest centre flattened by a direct hit. McShane, a terrific actor, wasn't one of the film's big stars; Battle of Britain was only his sixth picture (he'd appear in If It's Tuesday, It Must be Belgium the same year) but he registers the young pilot's shock with heartbreaking effect. When we see him next he's sleeping in a spare room in the family home of Shaw's "Skipper" – a wordless scene that follows the two men as they get ready for another day of battle and fills in the empathetic side of Shaw's otherwise stoic and demanding squadron leader.

One in three of Dowding's pilots in Fighter Command would either be killed, seriously wounded, or go missing. That wasn't even the highest of the war: air crews in RAF Bomber Command had a slightly less than fifty per cent chance of being killed, wounded or captured, while only one in four of Germany's U-boat crews would survive to V-E Day.

Michael Korda – son of production designer Vincent Korda and nephew of producer Alexander Korda (The Thief of Baghdad, The Third Man) and director Zoltan Korda (The Four Feathers, Sahara) – describes the young men who flew for Dowding in With Wings Like Eagles: A History of the Battle of Britain as "just out of school, commissioned pilot officers or noncommissioned sergeant pilots, tired, occasionally scared out of their wits, often sustained by a combination of adrenaline-producing excitement and a deep personal need 'not to let the side down,' many of them unexceptional marksmen only recently promoted from flying trainers to flying real fighters."

Korda describes the career of a fighter pilot in the Battle of Britain starkly:

"A pilot coming to a fighter squadron fresh out of an Operational Training Unit had almost no chance at all of surviving his first five 'sorties' in combat. If he did survive them, by sheer luck or superhuman natural skill, then his chance of surviving the next fifteen sorties increased on a rising curve as he gained experience and confidence. After twenty sorties, however, the law of numbers took over, and his chance of surviving began to decline rapidly toward zero again."

Hamilton's film does its best to reflect these brutal odds; inexperienced pilots are the earliest and most frequent casualties, but Korda's "law of numbers" plays out across the story. Of the three squadron leaders we meet at the start of the film, only Shaw's "Skipper" is still flying at the end, and Caine's Canfield is killed in action less than halfway through the story when his Spitfire explodes in mid-air.

The picture has a remarkably austere emotional tone, but it does give us a romance, of sorts. Plummer's Colin and York's Maggie are struggling, their marriage under strain with all the time spent apart. He's unsympathetic to her commitment to the WAAF and the young women she commands, many of whom become casualties of Luftwaffe air raids on the airfields at Kenley, Biggin Hill and Duxford. He calls her a "parade ground suffragette".

He pleads with her to get a posting close to his airfield and she resists, finally relenting when they spend a rare night together in London just when the city is (accidentally) bombed by off-course Luftwaffe bombers, triggering what would become the Blitz. Colin is shot down and survives, but he's disfigured when his plane catches fire. "You can get a posting near him," her station commander (Kenneth More) tells her when he breaks the news. "It's a miracle what they can do these days."

Battle of Britain sticks closely to the timeline and facts known at the time the picture was made, though specific details of what Dowding knew and when came from Ultra intercepts of German messages and were still covered by the Official Secrets Act. It shows that the battle was a war of attrition where Dowding's main concern was more with finding pilots than planes. Or as Olivier says at the height of the battle, "the essential arithmetic is that our young men will have to shoot down their young men at a rate of four to one, if we're to keep pace at all."

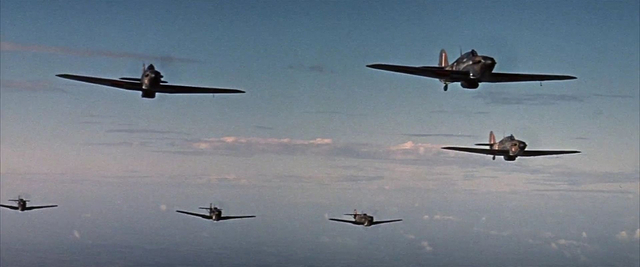

The film is famous for the care it put into putting the right planes into the air, back when almost all effects were practical. The biggest stroke of luck was that the air force of Franco's Spain had a huge inventory of CASA 2.111 bombers and HA-1112 Buchon fighters – Spanish-built versions of the He-111 and Bf 109. Group Captain Hamish Mahaddie was tasked with assembling planes for the film and discovered that of 109 Spitfires in the UK, on 27 were available and only 12 were flyable. Hurricanes were even rarer, with just six available of which half could fly.

Texans from the Confederate Air Force (now the Commemorative Air Force) brought four Messerschmidts and a Spitfire and a B-25 Mitchell bomber was converted into a camera plane and painted with a wild colour scheme that saw it dubbed the "psychedelic monster". Mahaddie could only find a single flyable Stuka dive bomber, so the scenes where Stukas attack the radar stations of Fighter Command's Chain Home system were done with remote control planes. Scarcity of surviving aircraft meant that the skies of Hamilton's film were notably lacking in Bf-110s, Ju 88s, Do 17s, Boulton Defiants or Bristol Beaufighters.

At the start of shooting there were only eight people in the unit tasked with aerial photography; that would grow to 740 people as the shooting schedule ballooned from six weeks to six months and the crew had to essentially invent modern air combat photography for widescreen colour cameras. The onscreen results are not just remarkable but are unlikely to be repeated again, and shots from Battle of Britain would be recycled over and over in documentaries as well as films and TV shows like Midway, Baa Baa Black Sheep, Piece of Cake, Hope and Glory and Dark Blue World.

All of that effort resulted in a spectacular sequence at the climax of the battle, on September 15, 1940, when both sides put everything they had in the sky over Britain. In a sequence scored to "Battle in the Air" from Sir William Walton's original score for the picture (judged inappropriate and largely replaced by one by Ron Goodwin) the work of the aerial unit is showcased and Hamilton's film reaches its climax. The film ends with the exhausted pilots waiting on the grass by their planes for an attack that never comes, as Hitler's invasion is called off and his army marches away – east, to invade Russia.

Hugh Dowding won the Battle of Britain but he lost another battle on the ground. Olivier delivers Dowding's lines with a melancholy, haunted tone; Dowding was probably the only man for the job but he was a poor politician and was ultimately undone, first by the conflict between Sir Keith Park, leader of No.11 Group, who took the brunt of the Luftwaffe's attacks (played in the film by Trevor Howard) and Trafford Leigh-Mallory (played by Patrick Wymark), head of No. 12 Group and proponent of a "big wing" fighter tactic that was usually too late to the battle to be useful.

Second there was his inability to stop the relentless night bombing of London by German bombers. It turned out that, for the most part, prime minister Stanley Baldwin was right and that "the bomber will always get through", though the Luftwaffe lost the Battle of Britain because they didn't make it back to their bases. Dowding, concerned with fighting the Germans in the air in daylight, didn't put as much energy into night fighters – or at least that was what his critics said, prime among them Air Marshall Sholto Douglas, a champion of Leigh-Mallory's.

Conspicuously absent from Battle of Britain is Douglas Bader, one of the most famous of the RAF's fighter aces, who had been played by Kenneth More in the 1956 biopic Reach for the Sky. Bader was a supporter of Leigh-Mallory and, as Korda puts it "played the role of Iago to Leigh-Mallory's Othello, and managed, whether by design or by accident, to bring out the worst in the character of No. 12 Group's Commander-in-Chief – his ambition; his taste for backstage intrigue and gossip at the Air Ministry; his desire to be popular with his own pilots; his resentment at having to follow Dowding's orders and play, as he saw it, second fiddle to Air Vice-Marshal Park, a 'colonial' from New Zealand."

The result was that Dowding, whose retirement had been deferred monthly during the Battle of Britain, was finally forced from leadership of Fighter Command two months after his victory. Sholto Douglas replaced him and Leigh-Mallory was given Park's command of No. 11 Group. After a predictably disastrous trip to the Unites States to give advice on war aviation – "bringing the Americans a message which they did not want to hear and which they would in any case ignore" as Korda writes – Dowding retired to devote himself to spiritualism and vegetarianism.

Wheelchair bound, he would visit the recreation of his old office at Hawkinge airfield in Kent during filming of Battle of Britain, where Olivier told him he spent the days "pretending to be you" and "making an awful mess of it." "Oh, I'm sure you are," replied Dowding.

The film made $13 million on a $14 million dollar budget (not helped by the cost of the aerial unit) and only turned a profit years later with home video sales. There's been plenty of pictures set during the Battle of Britain made since then, but Hamilton's film is still the only one that's about the whole of the battle as a hinge upon which history turns and not just a backdrop.

"Given time," Korda writes, "all historical events become controversial. That is the nature of things – we question and rewrite the past, glamorizing it or diminishing it according to our inclinations, or the social political views of the present."

"Nobody in academe," he adds, "gets tenure or a reputation in the media by examining the events of the past with approval, or by praising the decisions of past statesmen and military leaders as wise and sensible." And yet nobody has managed to debunk the victory of Dowding and the RAF over Goring's Luftwaffe. "As at Trafalgar," writes Korda, "the British got it triumphantly right" and that might explain the longevity of Guy Hamilton's Battle of Britain – a deeply unfashionable film that we'd never be able to make today.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.