My dear friend Kathy Shaidle used to joke that there was a new generation of filmgoers for whom the history of movies began with Star Wars. After a while we started joking that another one had subsequently arrived for whom that history began with the Star Wars prequels. What it meant was that the event horizon of film history – of history itself – was telescoping into an ever-briefer period.

Doing simple sums, the movies I grew up with in the '70s are as far away for these youngsters as the films of the '30s were for Kathy and me when we were their age. What we would learn about that golden age of the Hollywood studio system would rely on hearsay and received wisdom and the narrative laid out and overseen by historians and critics and the occasional testimony of the actors, writers and directors who had been there.

Which is, I suppose, how the youngsters have come to understand the movies of the '70s that Kathy and I saw in movie theatres or when they'd air to great fanfare as "special presentations" on prime-time television. The really curious ones will know about The Godfather, Easy Riders and Raging Bulls, Pauline Kael, Harold and Maude, Robert Evans and the dismantling of what was left of the studios by corporations. But what they won't know about was the shock of seeing the guy who played Charles Manson turn up in a movie with Lawrence of Arabia.

The Stunt Man was released in the summer of 1980, which is when I saw it, a high school kid dragged along by a movie-mad friend who'd end up having a long career in film. I'd never heard of the director (Richard Rush) or the female co-star, Barbara Hershey, a veteran with a filmography full of marginal pictures, the most notable of which were With Six You Get Eggroll and Boxcar Bertha.

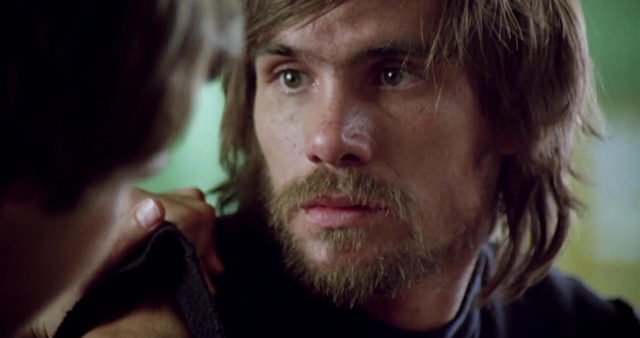

But I'd definitely heard of Peter O'Toole, the undeniable marquee star of the film, and it was with a shock of recognition that I recognized the actor playing the protagonist: Cameron, a Vietnam vet on the run from the law who ends up hiding in plain sight with the film crew led by Eli Cross, the charismatic and faintly sinister director played by O'Toole. Because that actor had scared the hell out of me and everyone my age barely four years earlier when he starred as Charles Manson in Helter Skelter.

Based on the book by Vincent Bugliosi, the prosecutor at the Manson Family trials, it aired over two nights on CBS in April of 1976. The Tate-LaBianca murders were something that happened in the periphery of our vision as children, the details blocked by our parents (though recounted in gruesome detail by older siblings who bought Bugliosi's book). Helter Skelter hit the air after weeks of commercials featuring Steve Railsback as Manson, but they didn't prepare us for the demonic intensity the actor brought to the role; as far as we were concerned Railsback was Charles Manson, and actual footage we'd see of the real Manson in subsequent years suffered by comparison with Railsback's version.

The first few minutes of The Stunt Man have a whiff of southern gothic – there's a buzzard on a telephone pole, a dog panting in the heat, linemen at work and a sheriff's car pulling up to a diner where they try and fail to arrest Cameron, who flees wearing their handcuffs. He steals bolt cutters from the linemen and ends up on a bridge where a vintage Duesenberg nearly runs him down but ends up going over the side and into the river.

Still on the run, he ends up in a seaside town where a movie crew is shooting a World War One picture – an action set piece that requires several cameras as Eli, the director, is (improbably) intent on shooting the whole scene in one take. Planes strafe the soldiers and bombs send bodies flying everywhere while crowds of onlookers watch and applaud from the seawall until the smoke clears and reveals blood, guts, limbs and corpses all over the sand.

Cameron's reaction hints at some barely controlled PTSD, but the bodies start to move and the stunt men and extras pull themselves out of the sand, picking up their ragged prosthetics while Eli congratulates them on a job well done. At the same time he's distracted by the news that the body of a stuntman, Bert, wasn't recovered from the car he drove off a bridge.

An old woman picks her way through the set asking Raymond (Adam Roarke), the leading man, for an autograph before losing her footing climbing back up the seawall and falling into the water. Cameron jumps in to rescue her and she pulls away her rubber skin to his shock. Nina (Hershey) is the film's leading lady and she'd wanted to see if she could fool everyone with her makeup before presenting it to Eli.

Jake (Alex Rocco), the local chief of police, pulls up to the set, enraged at the accident at the bridge and threatening to evict Eli and his crew before they can finish shooting. He's also looking for a fugitive but just as his attention rests on Cameron, Eli tells him that he's Bert, the missing stuntman, fresh from being pulled from the river. Eli offers Cameron a job on the spot, taking on Bert's job and identity as Raymond's stunt double, and re-christens him as "Lucky".

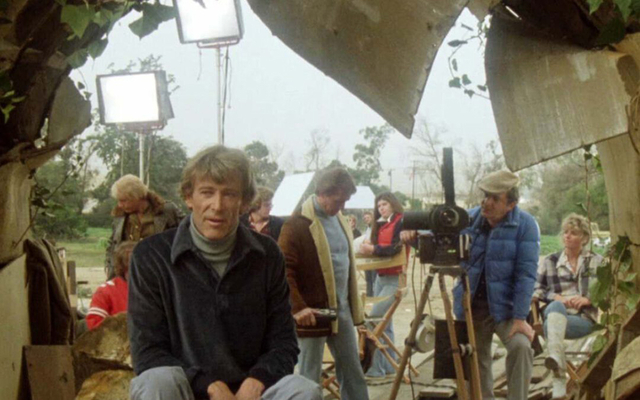

The story of how Richard Rush made The Stunt Man is nearly as unlikely as the film's plot. It began with a novel published in 1970 by Paul Brodeur, a writer and journalist who spent much of his career investigating the dangers of microwave radiation, electromagnetic fields, household detergents and asbestos.

Brodeur's Harvard classmate, documentary director Frederick Wiseman, was briefly meant to direct a movie adaptation and after his departure Columbia Pictures offered the film to Arthur Penn and Francois Truffaut, who both turned it down but borrowed aspects of the story for, respectively, Night Moves and Day for Night.

Columbia eventually settled on Rush to direct, but it wouldn't be that simple. Rush was one of the first graduates of UCLA's film program, and after working with the U.S. military to create TV propaganda programs during the Korean War, he began making commercials and industrial films before directing exploitation pictures like Too Soon to Love (1960), Hells Angles on Wheels (1967), Psych-Out and The Savage Seven (both 1968), working with independent producers and studios like American International.

In 1970 Rush made Getting Straight, a romantic comedy about campus politics and protest starring Elliott Gould and Candice Bergen. He followed it up with Freebie and the Bean in 1974, another comedy starring James Caan and Alan Arkin as misfit San Francisco cops. Both films had a zeitgeist-y appeal that made them hits with audiences at the time but would reduce them to footnotes when their cultural moment was over.

Rush was hired to direct One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest when a political crackdown in Czechoslovakia forced Milos Forman off the project, but when funding fell through he was replaced by Hal Ashby, who was out when Forman managed to defect to the West. All the while Rush had been working on The Stunt Man, buying the property from Columbia after disagreements over the direction he was taking the film.

Backers dropped out when Rush went to court with Warner Bros., who were making a film called The Stuntman; arbitration forced Warners to change their film's title to Hooper, which starred Burt Reynolds when it came out in 1978. Another deal fell through when Rush disagreed with his producer about casting. Filming finally began with new producers in 1978.

Cameron gets made over by the film's hair and makeup girl Denise (Sharon Farrell), and trained by Chuck (Charles Bail), the head of the stunt department. He begins an affair with Nina though Rush makes it clear that he's being seduced at the same time – platonically – by the emotionally manipulative Eli, the sort of director who runs his set like a Byzantine court, setting people against each other.

O'Toole admitted later that he based Eli largely on David Lean, the director who had made him a star in Lawrence of Arabia (1962), and who he recalled trying to emotionally break him during a long day's shooting where he made him do endless re-takes of the "Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo" scene under a pitiless sun.

Over the course of three days of hectic shooting Cameron starts to suspect that Eli is trying to kill him as the stunts he's asked to perform get more dangerous. Railsback sells his growing paranoia effortlessly; the actor's trademark intensity doesn't project stability in the calmest moments and suspicion that he's being played with by Eli and Nina and everyone else on the crew brings out that crazed, Mansonesque glare.

Eli insists that the film he's trying to make is his great anti-war statement, and he goads Sam (Allen Goorwitz), the screenwriter, to deliver scenes that underscore this message, under relentless deadline pressure. But the glimpses we get of the film Eli's making – a campy, bawdy slapstick period action picture – look more like Royal Flash (1975), Richard Lester's adaptation of the second of George MacDonald Fraser's comic Flashman novels, with Malcolm McDowell as the swashbuckling coward.

Rush is at pains to blur the line between Eli's anti-war fantasy and what passes for reality both on and off set, and characters comment on how their particular skills combine with the cheap tricks of "movie magic" to draw in audiences and overcome their disbelief. It's a movie about moviemaking, which is underlined for cinephiles by the setting that Eli and his crew use as both their set and their lodgings – the Hotel del Coronado near San Diego, where Billy Wilder had shot Some Like It Hot.

We get our first glimpse of Hershey's Nina in a commercial playing on the TV in the diner just before Cameron gets caught by the sheriffs. Film sets are assumed to be free fire zones of promiscuity, and Cameron is told that Nina has been involved with both Eli and Raymond, the leading man.

Hershey plays Nina like the classic leading lady – flighty, insecure, eager to please and emotionally volatile. Next to his fear of being arrested by Jake, she's what's keeping Cameron on Eli's set in spite of the threats to his life that increase with each new day of shooting.

In a documentary about the film's production made years after The Stunt Man was released, Rush reveals a scene that was cut from the film, where Cameron finds Nina in bed with Raymond. He confronts her, crazed with jealousy, but she shouts back that he has no right to make a claim on her, and the scene ends with the emotionally bruised Cameron admitting that she's right. It's a startlingly intimate scene full of the anxious sexual politics of the decade that preceded the film.

Rush states that it was the one scene in the picture he would never have cut. But it tested badly with audiences who said that it ruined their ability to sympathize with the characters, and despite having final cut on the film, he had agreed to keep the picture's running time close to ninety minutes and the scene was precisely the length of time he'd gone over that number. Eager to please and closer than he'd been in years to getting his movie into theatres, he left it on the cutting room floor. Perhaps he was tired; he'd already suffered a heart attack during production.

The scene also cuts down O'Toole's screen time, and it has to be understood that The Stunt Man would never have worked without O'Toole's Eli. The actor had been a major star for nearly twenty years and had already put on film most of the performances that would make his reputation in pictures like Lawrence, Becket, The Lion in Winter, Goodbye Mr. Chips and The Ruling Class. The previous years, however, had not been as memorable, and he'd ended the '70s with Zulu Dawn and – even worse – the porn epic Caligula.

The Stunt Man required O'Toole to pour on his famous charisma and he rose to the occasion, delivering the sixth of eight performances that got him nominated for an Oscar that he'd never win. (He'd lose that year to Robert De Niro in Raging Bull.) Eli is supposed to be the focus of everything in the film, a seducer, father figure, tyrant and confessor with a Mephistophelian aspect that was made explicit by the film's poster – an illustration of O'Toole's Eli as a horned demon behind the camera.

The Stunt Man reminded audiences of how great O'Toole was, as an actor and as a movie star, and it set him up for a career revival that would peak two years later with My Favorite Year, doing a turn as a thinly disguised satire of himself and his famously excessive lifestyle. That would get him a seventh Oscar nomination. His final nomination would come in 2006 for Venus, playing a downsized version of himself, an aging actor in his final, waning days.

Richard Rush is the missing figure in a generation of Hollywood mavericks; his biography echoes that of more famous directors like Coppola, Bogdanovich and Ashby, and his early career, complete with stints in exploitation films and the inevitable cameos by Jack Nicholson (who starred in Hells Angels on Wheels and Psych-Out). But he'd only make one more film after The Stunt Man – the erotic thriller Color of Night (1994) starring Bruce Willis, for which Rush didn't have final cut; during his battle with the producer he'd have another heart attack. Rush died in 2021.

Today The Stunt Man feels like the last film of the 1970s – trippy, shaggy and excessive, unapologetic, unironic and unconcerned with broad audiences or marketing; the creative expression of a director confident that his vision will find its audience and a movie industry still in love with its skill in creating illusions with whatever they had on set.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.