According to the people who make the rules that define this sort of thing, Louis Malle's Atlantic City, starring Burt Lancaster and Susan Sarandon, is the only Canadian film that has ever been nominated for a best picture Oscar. This is a useful fact, as it might help you win at bar trivia one day, and as someone who has been watching and writing about Canadian films for four decades, I'd go a step further and say that it might be the best Canadian film ever made – if you go by the rules made by the people who define this sort of thing.

Atlantic City was one of a group of wildly different pictures that got produced because of a momentary change in Canadian tax law that was meant to fund the country's fledgling movie industry, and it must have worked because hundreds of Hollywood films and TV shows were shot here – mostly in Vancouver and my hometown Toronto – in the decades that followed.

And you'll probably only know this if you're a Canadian of a certain generation watching the film and find yourself blurting out "Hey- it's the King of Kensington!" or "Isn't that the dude whose head blew up in Scanners?" The film might be the epitome of a Canadian success story – one where our participation was critical, while nobody outside the country knows nor cares.

Louis Malle made Atlantic City after he had moved to the US from France, between the morally dubious Pretty Baby and his rep cinema cult classic My Dinner with Andre. He had been unable to get backing for another project and was thinking about going back to Europe, as he says in an interview with My Dinner with Andre star Wallace Shawn (who has a small part as a waiter in Atlantic City) in an interview for the BBC arts program Arena.

He was offered "carte blanche – anything I wanted" from producers working with money from Canadian tax shelters. The only catch was that it was August and the film had to be done by the end of the year. Working with his friend, playwright John Guare, they came up with a story set in Atlantic City after spending just one day there together.

"All it was was trying to put together hastily a story that would permit us to shoot a fictional documentary," Malle said. "It was very improvised. It was the first time where I felt I was at ease at transposing documentary into fiction, fiction into documentary... In this country I see things shifting constantly. I go away for three months to Europe and I come back and I see that things have happened. I see that nothing lasts. You become a has-been in a year. It's like the course of history is speeding up so that what was topical three months ago is now out of fashion."

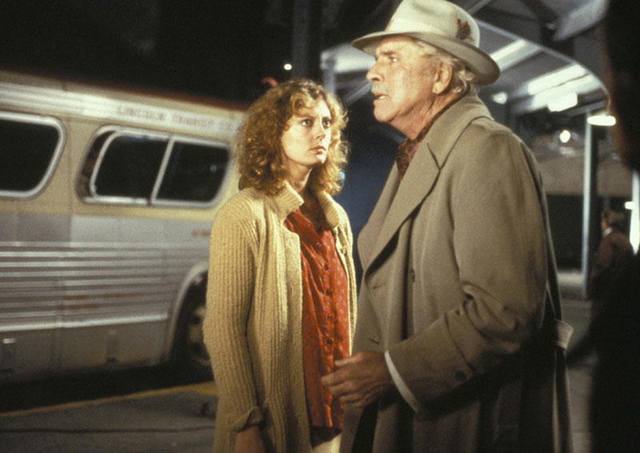

The story centres around Sally (Susan Sarandon), who we first see cutting lemons by her kitchen sink, rubbing the juice over her arms and shoulders by the window, where she's being watched by Lou (Burt Lancaster), her neighbour across the apartment building air shaft. Contemporary criticism of this is at pains to note that Sarandon's Sally is being objectified; there would, indeed, be a lot of such objectifying happening in films in the decade that followed.

Sally works at the oyster bar in a casino – the lemons are meant to get the seafood smell out when she gets home from work – but she's training to be a dealer under the very attentive tutelage of Joseph (Michel Piccoli), the floor boss. Lou is an aging small-time hood – a numbers runner with memories of Atlantic City's heyday, criminal and otherwise, under legendary gangsters like Nucky Thompson.

The apartment building they live in is just off the Boardwalk, across from a construction site and decorated with a billboard that reads "Atlantic City. You're on the map. Again." It's a bit of civic boosterism designed to celebrate an impending revival of the city, though the sign is a tombstone that indicates that Sally and Lou's apartment building is up next for an appointment with the wrecking ball.

Elsewhere we watch as another plotline heads toward Sally. A scruffy young man (Robert Joy) is monitoring a phone booth in Philadelphia – it's a drop for drugs and he scoops a package before Vinnie (Angus MacInnes), its intended recipient, can make a pickup. We see him behind the wheel of a car with his girlfriend (Hollis McLaren) driving across the swampy flatlands of southern New Jersey and turning just as they pass Lucy the Elephant – Atlantic City's famous roadside attraction (though technically just next door in Margate, a separate municipality full of beachside houses and time shares).

They arrive at Sally's casino looking like spectres from the decade just passed – hippie vagabonds in bell bottoms and rags carrying their overstuffed bags – and they're not a welcome sight for Sally. Dave (Joy) is her ex-husband, who she left when he got Chrissie (McLaren), her little sister, pregnant. She reluctantly agrees to put them up for the night but Dave tells her he has to do a little business, stealing her wallet as he heads out the door.

Dave needs a connection to start selling the cocaine he's stolen, and ends up in the Club Harlem, one of Atlantic City's hot spots from its golden age (on its last legs by the eighties, demolished in 1992). He catches the attention of Lou, who decides to help him out, partly because he sees some profit in the enterprise but mostly as an excuse to get closer to Sally.

Atlantic City was produced by Denis Héroux, an experienced Quebecois filmmaker who knew how to work Canada's federal film bureaucracy and saw an opportunity when the tax shelter era began in 1974. He had used this funding to make the 1976 low budget thriller The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane, starring Jodie Foster and Martin Sheen, as well as films by French new wave director Claude Chabrol.

"I forced Louis Malle to take a Canadian DOP (director of photography) and soundman and so on," Héroux recalled in an interview with Playback, the Canadian film industry trade magazine. "I told him, 'take it or leave it.' But Louis did insist on John Guare, who was a fabulous writer and Suzanne Baron, his regular editor. (Getting Malle to agree to cast) Burt Lancaster was difficult. We needed to raise $16 million. For tax shelter people, Lancaster was still a name, a star. Louis wanted James Mason, who couldn't raise us money – he wasn't a big enough name."

There's a myth that Malle only shot exteriors in Atlantic City but made the rest of the film on a Toronto soundstage to satisfy Canadian funding requirements – an audience member repeated it at a screening for the Austin Film Society in 2014, where it was introduced by director Richard Linklater (Slackers, Boyhood, Dazed & Confused). Thankfully this wasn't true – Malle shot on location in the city at a crucial moment in its history, and it adds immensely to the atmosphere of the picture.

In a montage at the start of the film Malle shows footage of the 1972 implosion of the Traymore Hotel, one of the many grand hotels that lined the Boardwalk, most built at the turn of the 20th century, when Atlantic City was reaching the pinnacle of its reputation as America's vacation destination (if by America you mean most of the eastern seaboard). The abiding relic of this period, of course, is the board game Monopoly, where the city's streets fill the playing board.

The city's decline began after World War 2, when first the automobile and then inexpensive air travel widened the options for Americans on holiday. The big old hotels – the Traymore, the Marlborough-Blenheim, the Chalfonte-Haddon Hall – were empty, and many closed. A 1969 fire that gutted the Steel Pier signalled the terminal phase of the old Atlantic City.

It would take a few years for a potential new Atlantic City to emerge – until a 1974 referendum on legalizing casino gambling, which aimed to make the city competition for Las Vegas. The Chalfonte-Haddon Hall was renovated into Resorts AC, and most of what remained of the old Boardwalk hotels were razed to make room for new casinos, while the city blocks behind the Boardwalk were flattened for parking lots.

At one point in the film Lou mentions that he hasn't left the city in twenty years. Perhaps the decay has taken hold so gradually that he doesn't really notice it. Lancaster's Lou is a kind of guide, or guardian, for outsiders in Atlantic City. First there was Grace (Kate Reid), who showed up there during the war for a Betty Grable lookalike contest; Lou took her under his wing but she married his boss. Now she's a widow, confined to her bed, and Lou is her servant and gigolo, for which he gets a little money and a lot of abuse.

Then there's Sally, who's trying to convince herself that she's in Atlantic City for the long haul, provided she can get her dream job as a casino dealer, as a springboard to working in Monaco one day. Lou's attraction to her is as paternal as it is romantic. And finally there's Dave, a dirtbag and wannabe criminal who wouldn't have lasted an hour there without Lou to guide and protect him.

While he leaves Chrissie, a hippie simpleton, with Grace to administer some half-baked tantric massage, Dave shows Lou how to cut his cocaine with baby laxative to make $4000 worth of blow get twice that on the street. He asks Lou to be his front man and make his first sale, to Alfie (Al Waxman), who's running a nonstop card game out of his smoke-filled hotel room. Unfortunately for Dave he's spotted by Vinnie and Felix (Moses Znaimer), the two gangsters he ripped off in Philadelphia; there's a fantastic chase scene up and down a car elevator but in the end Dave doesn't make it past a day in Atlantic City.

The tax shelter era in Canadian film production also began in 1974, when the federal government allowed a one hundred percent deductible on taxable income for anyone investing that money in Canadian movies. This was meant to encourage film production in the country with the hope of building production and post-production facilities and training a new generation of film technicians.

It was typical of Canada's soft nationalism after the 1967 centennial – an initiative that was supposed to produce quality pictures featuring Canadian themes, stories and talent and at first it worked with a movie adaptation of Mordecai Richler's novel The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz and Lies My Father Told Me, both set in Montreal's Jewish community. But its biggest box office hits weren't exactly the kind of picture cultural bureaucrats had in mind: Ivan Reitman's Meatballs, the smutty comedy Porky's and horror films like The Changeling, Prom Night and My Bloody Valentine.

Critics here were particularly appalled at a creepy low budget horror film called Shivers; Robert Fulford, writing in Saturday Night magazine, called it "an atrocity, a disgrace to everyone connected with it – including the taxpayers... If using public money to produce films like this is the only way that English Canada can have a film industry, then perhaps English Canada should not have a film industry." It even caused a debate in the House of Commons.

The director of Shivers, David Cronenberg, would ultimately be acclaimed worldwide for pioneering the genre of "body horror" as well as his "serious" films like Crash, A History of Violence and Eastern Promises. Additionally the tax shelter era launched the career of Jamie Lee Curtis, star of Prom Night and Terror Train.

Susan Sarandon had finished her first full decade as a movie actress, in films like Joe, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, The Other Side of Midnight and King of the Gypsies. She was a working actress of note but hardly the movie star she'd be a decade later, after making The Hunger, The Witches of Eastwick and Bull Durham. She was also Louis Malle's girlfriend while making Atlantic City, where she gives what can only be described as a luminous performance.

For the purpose of additional Canadian content, though, her Sally is supposed to be from Saskatchewan – Moose Jaw, to be exact. "It's near Medicine Hat," she tells someone, though of course it isn't: Moose Jaw is closer to Regina, the provincial capital, and Medicine Hat is all the way across the border in Alberta. But dropping those names into the script evokes a Canada where the cities sound like Hudson's Bay Company trading posts. Her ex-husband mocks her by saying that if she was back home she'd be "making moose jam and putting out for lumber jacks." I've never heard of moose jam, and Moose Jaw is in the middle of the prairies, flat as a pancake and nearly treeless. These are the kinds of details peppered through tax shelter films that make Canadians wince.

Burt Lancaster had come off a decade that was generally better than many of his contemporaries – roles in films like Airport, Ulzana's Raid, Executive Action, 1900, Twilight's Last Gleaming and Go Tell the Spartans. He could still draw on that leading man energy, even in a film where the age difference with his co-star is so glaring. (He was close to 70 when he made Atlantic City, while Sarandon was half his age.)

There's a fantastic scene where Sally has to identify her ex-husband's body and finds herself in the Frank Sinatra Wing of the Atlantic City Medical Center. Robert Goulet, complete with a chorus line of showgirls, is presenting a cheque to the hospital and entertaining patients and staff by singing Paul Anka's "Atlantic City, My Old Friend", serenading Sally through the glass of a phone booth while she phones Moose Jaw to try and tell Dave's parents about his murder.

Besides being so audacious, even surreal, the scene underscores how lost Sally is in this strange, crass, gaudy and decaying city, so she allows Lou to become her protector. For his part he's built up an image of himself as a mobster – a well-connected killer who made his bones when the city and its criminal enterprises were at their height.

But it's all a myth that comes apart when he and Sally are cornered by Vinnie and Felix, who slap Sally around and tear her handbag and its contents apart looking for either the cocaine or the money Dave took from them. Lou stands frozen, his head down, overcome with shame that he couldn't protect her – shattering a self-serving fantasy that echoes Lancaster's performance in The Swimmer.

Lou tries to find comfort at the tables in the casino, but he's cornered there by Sally, who's been fired after her manager discovers that her ex-husband had a criminal record. Felix and Vinnie are shadowing Lou when she confronts him, and she's humiliated when Joseph, now her ex-boss, tries to pimp her out to a high roller.

Lou gets drunk and tries to escape the city but Sally pulls him off a bus by pretending to be his daughter, concerned for her senile father. They're tracked down by Felix and Vinnie, who don't count on the revolver Lou's carrying in his trench coat pocket. After gunning the mobsters down Lou is overcome with boyish pride in finally plugging someone, celebrating his first killings with Sally and even phoning Grace from a motel while they're on the run to brag.

The ending is bittersweet but it gives Sally and Lou second chances that feel deserved but won't amount to much ultimately. It's hard not to imagine the film being made thirty years earlier in black and white – a minor noir directed by Robert Wise, with Edward G. Robinson as Lou and Barbara Stanwyck as Sally, or maybe Lizabeth Scott if Daryl F. Zanuck at Fox thought Stanwyck was too old for the part.

Atlantic City ended up with five Oscar nominations as well as several BAFTAs, awards from the National Society of Film Critics and the New York Film Critics Circle and Genies (Canada's version of an Oscar) for Sarandon and Reid. It has a 100% critics' rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

Atlantic City put itself back on the map again with an orgy of casino and resort building that included Bally's, Caesar's Palace and the (defunct) Trump Taj Mahal; which replaced those beautiful hotels with much larger, much uglier eyesores in glass and stucco. But they were never able to compete with Vegas and once states like New York, Connecticut and Delaware legalized gambling they suffered from competition keeping gamblers closer to home.

The Atlantic City I visited six years ago is much improved from when Malle filmed there, but it never got the revival it hoped for when it was demolishing its past. Off the Boardwalk the Knife and Fork Inn, where Wallace Shawn waited on Lou and Sally, is still there, as is White House Subs, where Lou offered to take care of Sally's ex-husband's body. The city itself, behind the hotels, looks half empty after the parking lots and wrecking balls cleared block after block. It would be a great place to make a movie about desperate people, even without Canadian money.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.