The first shot of William Dieterle's 1944 drama I'll Be Seeing You sets a scene that its audience at the time would have understood implicitly, but which might take a bit of education for us to grasp. Mary Marshall (Ginger Rogers) walks through a crowded train station, the camera following her from above. Elsewhere in the same crowd Dieterle's camera picks up Zach Morgan (Joseph Cotten), a soldier, looking as wary and tentative as Mary.

Rogers stops at a newsstand and asks for a pack of gum and is told that there's none to be had; she asks for a chocolate almond bar and gets the same answer – they haven't seen gum or chocolate for at least a couple of years. "Where have you been?" the stall owner asks her. The crowd is full of men and women in uniform; the trains are packed. Welcome to the U.S. home front in the grip of total war.

Chewing gum was rationed during the war, with most of it destined for soldiers' K-ration and C-ration packs, and even the tinfoil that wrapped a stick of gum was scarce. Chocolate was similarly rationed, processed into heat-resistant D-ration bars for the armed forces. By 1944, the average citizen would have known what they could buy for points and what was a rare luxury they weren't likely to see until the war was over; shoes were hard to find and worn until they fell apart, toothpaste was only obtainable by exchanging an empty tube, and as bad as these shortages were they knew that things were worse in the U.K.

Mary's cluelessness is our first hint that she doesn't fit into this teeming crowd. Zach's stricken expression is another; sitting across from Mary on a train headed west, he's conspicuously distant from the boisterous sailors and G.I.s on leave. Despite the teeming crowds in motion there's a heaviness hanging over the story, established within minutes of the credits rolling.

This is probably what sparks an attraction between them. She tells him that she's a traveling saleswoman for a dress company on her way to visit family in Pinehill; he tells her that he's on his way there to visit his sister. We know they're both lying but when they get off the train he asks where he can call her and she's gives him her uncle's name.

She's staying with her Aunt Sarah (Spring Byington) and Uncle Henry (Tom Tully), that much is true, but she's there on furlough from prison, where she's halfway through a six-year sentence for some as-yet unnamed crime. He goes straight to an austere little room at the YMCA; there's no sister as Zach is also on leave from a military hospital where he's being treated for shell shock. His doctor thought it would be good for him to go somewhere on his own to see if he can find his way back into society in what sounds like "sink or swim" therapy.

Aunt Sarah and Uncle Henry's home is the picture of middle-class middle America as fondly imagined by Hollywood, all Victorian gingerbread and wood panelling and gemütlichkeit clutter. Sarah and Henry are similarly warm and comforting, taking in their niece without judgment; the only harsh note is Mary's teenage cousin Barbara (Shirley Temple), who has filled the room they're sharing with little handwritten signs marking what belongs to her as if anticipating being looted by Mary over the holidays.

Because I'll Be Seeing You is a Christmas movie, with snatches of carols like "Jingle Bells" quoted in composer Daniele Amfitheatrof's score. Taking its cue from Charles Dickens, the story imagines a Christmas setting as a test of goodwill and redemption, a time of year when the stakes are higher and the rewards potentially more profound.

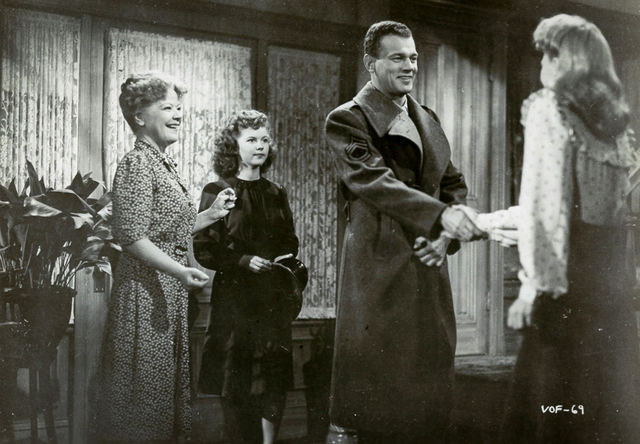

It doesn't take long for Zach to call on Mary and meet the approval of her aunt and uncle. He complicates his opening lie by saying that he's at the YMCA after discovering that his sister had moved west for war work but tells Mary the truth not long after. The test of their budding romance – and the principal engine of the film's drama – is when or if she'll come clean about herself, and how he'll react.

I'll Be Seeing You was produced by David O. Selznick for Vanguard Films – the company he set up after he shut down Selznick International Pictures but still had obligations to fulfill with United Artists. Like most Selznick films – at least until Duel in the Sun – it was considered a quality picture for adult audiences, sure to make the Oscar nominations. (Released in the first week of January 1945, the film fell into the awkward gap of Academy eligibility, though another Selznick homefront drama, Since You Went Away, got nine nominations but only one win – for best original score – in the tidal wave that swept in behind Going My Way.)

The story was based on Double Furlough, a radio play by Charles Martin, about whom the internet has no substantial information except that he shares the name with a contemporary author of manly fiction with outdoor settings. William Dieterle, the director, was German-born and part of the wave of talent that came to Hollywood as the political situation in Germany turned dark. (Dieterle was notably prescient, leaving Berlin for the U.S. in 1930.)

He's known today for biopics like The Story of Louis Pasteur (1935), The Life of Emile Zola (1937) and Dr. Ehrlich's Magic Bullet (1940) as well as the supernatural drama The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941). He was a favorite of Selznick, directing his mistress/future wife Jennifer Jones in Love Letters and Portrait of Jennie, but would have the misfortune to be one of the uncredited directors hired and fired by Selznick on Duel in the Sun.

Dieterle's direction is measured, focused on his misfit/outcast leads without the sort of distracting side plots or comic relief many of his peers would have resorted to in an effort to lighten the tone. It's a testament to how much room Selznick could give his directors when he was distracted and they weren't working on one of his pet projects. (Which would be any starring Jennifer Jones.)

The film has a gravity – an earnestness that it shares with Since You Went Away as well as Vincente Minnelli's The Clock (1945), whose plot more than faintly echoes Dieterle's picture, as well as postwar films like The Best Years of Our Lives and The Bishop's Wife, another low-key Christmas picture. Taken together they comprise a sample of the zeitgeist on the American homefront while the country went about the grim but inevitably victorious business of winning the war and the equally difficult task of creating a new society in its aftermath.

Or at least that's how it looks to us today. You can't help but envy the unified purpose that has brought everyone together in a place like Pinehill, through grief and duty and resignation to the demands of history happening with pressing, undeniable force. Maybe it's an illusion – Hollywood's finely-tuned and artful propaganda at work – but it's hard to imagine the same shared purpose galvanizing people today.

When Selznick and Dore Schary announced production on the film, Joan Fontaine, under contract with Selznick, was meant to play Mary but when she refused, saying she didn't want to play another "sad sack", he suspended her for eight months. Rogers, in the post-Astaire second act of her career, had been working with a string of good to great directors like William Wellman (Roxie Hart), Billy Wilder (The Major and the Minor), Leo McCarey (Once Upon a Honeymoon), Edward Dmytryk (Tender Comrade) and Mitchell Leisen (Lady in the Dark).

Since I started writing this column I've ended up seeing more Rogers films than I had since my first infatuation with classic Astaire-Rogers musicals, and I've come to the conclusion that she hasn't gotten enough credit as an actress. Her Mary struggles with the unjustness of her sentence and living with a damaged reputation; she confesses her worries to Byington's Aunt Sarah but never comes across like a victim. She lets us see the effort of keeping the truth from Zach, afraid of his rejection, but maintains a restraint that helps hold the picture at arms length from mere melodrama.

"Can there be any other major star who was so variable, even from film to film, as she was" asks James Harvey in Romantic Comedy in Hollywood from Lubitsch to Sturges, "alternating performances of plain, unaffected dignity and charm, like the heroines of Carefree (1938) and Kitty Foyle, with mannered an painfully misjudged ones, like Vivacious Lady (1938), the film before Carefree, or Tom, Dick and Harry (1940), the film after Kitty Foyle?"

"Rogers' wariness has always made her a problematic sort of screwball, or romantic, heroine," he writes about Rogers in Fifth Avenue Girl. "But it's also, as in the Astaire films, what's made her interesting and complex, what's given her special style and attractiveness."

She might look a bit too glamorous for a jailbird in I'll Be Seeing You, but that's probably modern audiences being unable to read period cues. Her tailored outfits and hats – designed by Edith Head – are exactly the sorts of things a woman who's been in prison since before Pearl Harbor would have to wear while given furlough in a society where style is dictated by uniforms and shortages.

And you certainly have to admire her for walking the trails and clambering over rocks in heels in an outdoor scene with Cotten's Zach; it reminds you of the old saying about Rogers doing everything Astaire did but backwards and in pumps.

Cotten also does a fine job as the shell-shocked Pacific veteran (complete with Purple Heart). Cotten's work was always notable for its restraint – a matter-of-fact delivery that looks very modern in the context of golden age Hollywood – and he's perfect as the tentative, emotionally scarred soldier, suffering not just from what we now call PTSD but from social judgment: he walks away from that train station newsstand at the beginning with a magazine featuring an article about "The Problem of the Neuro-Psychiatric Soldier".

Cotton's Zach is frightened he's going to end up like a World War 1 veteran he and Mary meet, his face screwed up in an uncontrollable tic. For most of the film, he's fighting not to slip into catatonia, but his major battle as we see it is recovering his "timing" – the physical grace he once had as an athlete, wrecked by nerves. Even near the end of the second major war fought after psychology had been accepted as medical science, PTSD was still a mystery, so it's impressive how Cotten plays Zach without implying that he's "screwy".

Mary, on the other hand, is suffering from an imbalance in the justice system. She tells Barbara why she's in jail: invited to a party by her boss, she discovers it was a pretense to get her alone, and while fighting off date rape she accidentally pushes him out a 14th story window and gets sentenced to six years for involuntary manslaughter. No one who knows about it thinks her punishment was justified, but the sentence stands nonetheless.

The film's title came from the song Bing Crosby made a hit in 1944 and was suggested by Schary. Originally written for a Broadway flop in 1938 by Sammy Fain and Irving Kahal, it was covered by Dick Todd and Frank Sinatra with Tommy Dorsey in 1940, so it began its life in a peacetime context. But it was Crosby's version that took it to the top of the hit parade, imbuing it with the same wartime themes of homesickness and melancholy that Vera Lynn packed into "We'll Meet Again".

If Dieterle had let the story blossom into melodrama it would have swamped the message of the film – that the end of the war would demand taking account of all the damage, trauma and grief that had collected over fifteen years of Depression and war and making a working society again; a proposition that demanded a lot of fresh starts. It's the message writ large in William Wyler's acclaimed The Best Years of Our Lives, but I'll Be Seeing You expresses it more subtly.

Wrapping the message in a Christmas film probably helped, especially during wartime rationing, where gifts are few and understated and the ritual of family and food dominate. The southwest locale means a snow-free holiday, paring away the visual cliches of the Christmas picture. In the context of Christmas movies, I'll Be Seeing You is almost ascetic – perhaps the perfect holiday picture for anyone exhausted by the genre.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.