At midnight on December 31st 1999, how did the world's only superpower celebrate the passing of the soi-disant millennium and a thousand years of cultural inheritance? Shakespeare? No. Mozart? Not a chance. Instead, Bill Clinton, the Lounge-Lizard-In-Chief, turned up at the Lincoln Memorial to listen to Tom Jones crank out well-loved favorites like "It's Not Unusual" - which, by happy coincidence, was also the President's defense to Paula Jones' allegations about the curvature of his, ah, "distinguishing characteristics". Millennia come and go, and Clinton is stooped and aged now, but the indestructible Welsh boyo is still on stage 250 nights a year driving women wild with "It's Not Unusual" at an age when, sadly, for many men it's all too unusual.

Timeless joke:

Patient: Give it to me straight, Doc.

Doctor: Well, I'm afraid you've got Tom Jones Disease.

Patient: Tom Jones Disease? I've never heard of it. Is it common?

Doctor: Well, it's not unusual.

No, it's not:

In my disc-jockey days, the thing I found burdensome was the requirement to be cheery and positive every day of the week. If you chanced to come into the studio with care and woe hanging round your shoulders, even if you didn't utter a solitary downbeat word, the audience could somehow discern you were a little low and glum. And that's not good for ratings.

And then one morning I stumbled on the perfect cure: I found, if you kept a copy of "It's Not Unusual" handy, the sheer exhilaration of that intro was sufficiently infectious to banish the blues and that, after bouncing a timecheck or weather update over that band, no one listening could tell your best friend had just run off with your girl and the bastards had taken your dear old dog with them just to rub it in.

The man who wrote that song and arranged that unforgettable intro died last week at the age of 83. Les Reed was a terrific songwriter and a brilliant arranger - the two things sound as if they should go together, but as a practical matter they don't: Billy May was one of the greatest arrangers of all time, but his songwriting royalties rest pretty much on "I Tawt I Taw A Puddy Tat", and that's one more bona fide hit than Nelson Riddle can claim. But Reed was a genuinely gifted pop composer and arranger, who knew how to make other men's songs sound good and his own sound great. He was born in Woking in Surrey in 1935, and at the age of six had his first piano lesson from Rita Row, the lady who lived on the other side of the allotment from him. He took to the piano, and the accordion and the vibraphone, and Mrs Row tutored him all the way through to the entrance exams for the London College of Music. Les was called up for national service with the Royal East Kent Regiment and sent to Germany, Denmark and the Balkans, where he did, nevertheless, get to play clarinet and write the arrangements for the Buffs, the regimental band. Back in Blighty, a guitarist called him up to ask if he'd like to play piano for the season at a Butlin's holiday camp. The guitarist was Vic Flick, who went on to join the John Barry Seven, and recommended Les for piano player - which is about as good as it could get for a young British musician in the late Fifties. That's Vic providing the unforgettable guitar lead, with Les on piano, on "The James Bond Theme".

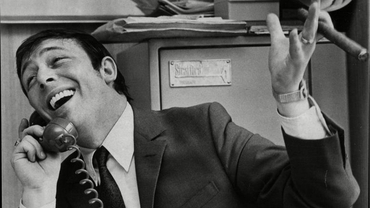

A brief diversion: Before the Beatles merged the performing and songwriting functions, pop stars looked like matinée idols, and songwriters looked like accountants or salesmen or store clerks - prosperous rotarians or, at the rougher end, fellows who'd been sleeping in the park for a couple of nights. Frank Sinatra looks like "Come Fly With Me"; Sammy Cahn, who wrote it, doesn't. But there are occasional exceptions: John Barry, squire of models and starlets, had the sheen of 007 himself. And Les Reed, if not quite in that league, always had the polish and style (see above right) of a man who could pinch-hit for a missing telly host or lounge act.

He had been writing songs - words and music - since he was in short pants, starting with one called "Oh, Mother Dear", for his dear old mum. In long trousers, he moved on to what Ira Gershwin called "the subject preponderant in Songdom" - boy meets girl. Les met Geoff Stephens and they wrote "Tell Me When", which was a hit for the Applejacks in 1964. Les and Geoff went on to write many other songs, including their masterpiece, "There's a Kind of Hush (All Over the World Tonight)", which Herman's Hermits made a monster hit all over the world now and forever. I love the melody Reed came up with, and maybe we'll do that for a Song of the Week in the weeks ahead.

While Les had been a piano player at the Lido in the West End, he'd auditioned a would-be singer called Barry Mason but turned him down in favor of a lady called Fluffles Malone, who had the rare talent of being able to counter-rotate not only the tassles on her breasts but those on her bottom, which Barry, although he has a certain undeniable manic energy, could never do. The next time Reed bumped into Mason the latter was working as a lyricist, and together the lads came up with "Delilah" (which I write about in my book A Song for the Season). You can hear Reed's orchestrational skills on the great melodramatic thunderstorm he provides for the intro and you wonder how the hell any lyricist could ever rise to the near operatic stakes of the arrangement. And then Barry Mason leaps in with a gloriously overripe opening whose emphatic internal rhymes and lurid imagery match the music perfectly:

I saw the light on the night that I passed by her window

I saw the flickering shadows of love on her blind...

What a (literal) killer image - a crime passionel set to music. I went round to Barry Mason's house in North London one morning a few years ago to find a great bouncing Tigger of a chap full of enthusiasm for all kinds of projects that seemed to me to have certain obvious flaws: He was working on a musical about surfing, which sounded problematic to me, because there didn't seem to be any kind of way to recreate California surfing in a West End theatre that wouldn't look stilted and clunky and faintly ridiculous. But he was irrepressible about that, and about everything else, too.

By that time, Les Reed was living out in the Home Counties golf-club belt and resting on his royalties. From the mid-Sixties on, it was hard to find a week when there wasn't some or other Reed composition on the British charts. On just one wet Sunday afternoon with nothing else to do, he and Barry Mason composed seven songs, five of which made the Top Ten – "I'm Coming Home", "The Last Waltz", "I Pretend", "Love Is All", and my personal favorite , the lovely "Les Bicyclettes de Belsize". The only single of theirs not to make the charts was a song they wrote for Doctor Who sidekick Frazer Hines called "Who's Doctor Who?" But that level of success can't last, and, when it faded, the formerly tireless Reed was content to potter: an occasional film score or orchestral commission here, a jingle package or awareness-raising charity song there... He wrote a couple of musicals whose subjects didn't quite have the size required in the age of Les Miz and Phantom. But there were plenty of lifetime achievement awards, and, on the occasions when I ran into him at various events in town, he was far more modest than a chap with his catalogue should be.

To mark his passing, however, I thought we'd focus on what's either his second hit, after "Tell Me When", or third, if you include "Everybody Knows", which Steve Lawrence took to big hit position 72 in the Billboard Hot One Hundred in 1964. At any rate, I regard it as Les Reed's first truly great song, and it echoes down the generations. The last time I saw it sung live was by Tom Jones in Vegas, and I confess, watching Tom dodge what looked like the London Blitz re-enacted in women's knickers, it wasn't always easy to tell how good the song was. If Tom seems too old for the lingerie blitzkrieg, the point about Tom Jones is that he's always been too old. As is well known, he's the only Welshman in history not to be born with the surname Jones; instead it's his middle name: Thomas Jones Woodward. By 1964 Tommy Woodward was restyling himself "Tommy Scott", "the twisting vocalist from Pontypridd". One night at the Top Hat Club in Cwmtillery in walked Gordon Mills, a wannabe music-biz mover and shaker who was in Wales to visit his mum. Mills figured that, at 24, Tommy was too old to be a rock'n'roller, but he was in the market for a British Sinatra.

Les Reed had run into Gordon Mills on tour when he was playing piano for John Barry and Mills was a jobbing mouth-organist. So Mills telephoned Reed and asked him if he wanted to see this Welsh fellow who was singing at a cinema in Slough. Tommy Scott walked out on stage and Les was horrified - by the spray-on trousers with a lucky rabbit's foot dangling from his waist, by the black frilly silk shirt open to the navel, by the impenetrable thicket of chest hair with medallions nestling therein. But then Tommy opened his mouth and let rip - and suddenly it all made sense.

Mills rechristened Tommy Scott "Tom Jones", and nothing happened. He wanted to make hit records, and Mills had yet to get him a recording contract. Tom was broke and so, when he was in London, Gordon Mills let him stay in the spare room at his pad in Notting Hill. Mrs Jones wasn't impressed: there was no carpet on the stairs, just bare boards, and, penniless as they were, the Joneses nevertheless had carpeted stairs back in Pontypridd. Mills turned out to be one of those fellows who was always short of money: One day, after he'd sold his car and his wristwatch, he dragged Jones along to a meeting at the National Westminster Bank for a loan application. When the manager demanded to know what he'd put up for collateral, Mills pointed to Jones: "Him. He's going to be the biggest star in the world." He got the loan.

Back at the flat, Mills was driving Jones nuts, because the latter would be kipping in the spare room and the former would be at the ol' joanna hammering out a new song. He had two chords and three words - "It's not unusual" - and he pounded and bellowed them over and over without ever being able to get them to go anywhere.

And then Les Reed called. And Mills asked him to come round and lend a hand. And Reed liked the title and was able to get it on the road and off and running:

It's Not Unusual to be loved by anyone

It's Not Unusual to have fun with anyone

But when I see you hanging about with anyone

It's Not Unusual to see me cry

I wanna die...

And, by the time it was finished, the only person who wanted to die was Tom Jones. Because, having listened to Gordon Mills yelling day in day out "It's not unusual" to the point where it became sledgehammeringly all too usual, Tom assumed he'd be getting first crack at the song. Instead, Mills and Reed announced that they'd just written Sandie Shaw's next hit. Miss Shaw had burst on the scene a few weeks earlier with "Always Something There To Remind Me", and they figured "It's Not Unusual" would be a perfect follow-up.

But not to worry, Reed and Mills told Tom Jones: you can do the demo. The grinding of teeth must have drowned out the jangling of his chest-hair medallions and rabbit's foot, but Tom sportingly agreed. And so a beery hairy boyo found himself in the studio making like a barefoot Essex girl:

It's Not Unusual to go out at any time

But when I see you out and about it's such a crime

If you should ever want to be loved by anyone

It's Not Unusual...

It was rather subdued by comparison with the version we know now - no bass, no brass - but it was still too unusual for Sandie's manager, the formidable Eve Taylor. Miss Taylor played an important role in the careers of John Barry, Adam Faith, Dusty Springfield, and the comedian Larry Grayson, whose catchphrase derived from Eve's hissed injunction to her clients whenever they wished to discuss money with her: "Shut that door!" At any rate, Eve Taylor shut the door on "It's Not Unusual" because Sandie Shaw is said to have heard the demo and said "Whoever's singing that should release it himself."

Reed and Mills were not yet ready to give up on getting it to a big star, and they determined to pitch it to Frankie Vaughan. Britain's big-voiced balladeer of the late Fifties, Vaughan had had his most recent Number One with "Tower of Strength", which one can easily imagine as a Tom Jones song. So they went back to the studio for another demo, and de-Sandified the song. For example, that little descending instrumental fill at the end of the lines:

It's Not Unusual to be loved by anyone

(b'dabba-dabba-daaaaa)

That wasn't brass in the Sandie Shaw version. Instead, Reed and Mills just sang it, like a couple of gay Ladybirds, as Jones once described it to me, in acknowledgment of Britain's all-time great female backing singers. It was both camp and undernourished - so Les Reed rewrote it for trombone and they went back to the studio. And it was livelier than the Sandie version but still not quite there, and anyway Frankie Vaughan wasn't interested either. So faute de mieux they let Tom Jones have it because nobody else wanted it.

And at that point Les Reed decides to go for it, and throws in some electric guitar and fires up full brass for that bum-ba-dum intro, transforming the entire feel. And suddenly it's a Tom Jones song, even though no such thing has ever existed before. But listen to the way Jones really bounces off that staccato middle section:

It's Not Unusual

It happens ev'ry day

No matter what you say

You'll find it happens all the ti-i-i-ime

Love will never do

What you want it to

Why can't this crazy love be mine? Whoa-o-o-o-oh...

A shame about that false rhyme "time"/"mine", but the song didn't have a real lyricist: Gordon Mills had a good idea, and Les Reed fleshed it out, writing most of the music and words, which start out in that first section eschewing rhyme in favor of identities: "anyone"/"anyone"/"anyone". In the second section, Jones really bites on the words - "out" and "about" - to the point that it wouldn't really matter if they didn't rhyme. So it's a bit of a shame that, in the nearest to a conventionally rhymed section of the song, Reed and Mills rely on something as tired as "time" and "mine". But this is a small blemish - and, as I say, Reed was a composer writing not with a lyricist but with a music-biz manager who liked to dabble in songwriting. Perhaps that's why the lyric is strangely impenetrable: It's not unusual to be loved by anyone? What does that mean? Surely it's not unusual to be loved by someone? Otherwise, if you can be loved by anyone, what's the point of it?

Heigh-ho. Don't overthink it.

There are a lot of legends about that studio date: It's a persistent rumor that the guitarist on the track is Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin. In fact, it's Joe Moretti, who played on "Shakin' All Over". But it is true that the session pianist didn't show up, so Les Reed went next door to the Gioconda coffee bar, which was so close that you could hear what was happening in the studio through the walls - which is why it was a popular hangout for unemployed musicians: because, if the trombone player keeled over from a massive stroke, you'd been sitting there nursing your cuppa for a couple of hours and knew the part. So they fished out a pianist, name of Reg Dwight, who subsequently changed his name to Elton John. And this time, at the playback at the end of the session, everyone knew they weren't listening to a demo:

It's Not Unusual to be mad with anyone

It's Not Unusual to be sad with anyone

But if I ever find that you've changed at anytime

It's Not Unusual to find out I'm in love with you oh-whoa-whoa-whoa-whoa-whoa...

And it faded away after two minutes ...because it had been arranged as a demonstration of the song, and why make a long demo? Instead, it was Tom Jones' first record, and a few weeks later hit Number One on the UK charts.

Unlike most Denmark Street songwriters, Reed was a trained musician and liked all sorts - big band, brass band, opera, symphonic... Aside from that guitar solo, there's nothing really rock about the track. It operates in the same semi-jazz-plus-electric-guitar terrain as the John Barry Seven did. And, whatever the lyric, the tune - including that little descending riff - has tickled all sorts of fancies. In the late Sixties, when great jazz arrangers were being leaned on by their record companies to do quickie knock-off albums of recent pop singles, "It's Not Unusual" became, for the swingers, one of the least traumatizing choices. Here, from his LP The Rock-Jazz Incident, is Mel Tormé's old pal Marty Paich:

Tom Jones reckoned the brass in "It's Not Unusual" made it sound like a Motown record. But everyone else seems to have concluded it makes it an incipient jazz standard. Half-a-century on from Marty Paich, here's Clare Teal (whose Sunday-night BBC show is one of the last holdouts for good music on Radio 2) trying to de-Tom the song:

But, with all due respect to the talented Miss Teal and the peerless Mr Paich, I think what everyone loves about this song is the perfect match of the original arrangement and the original singer. In the Sixties, Tom Jones was irredeemably (as they say in Britain) naff; the Velvet Underground were cool. In the Seventies, he was still naff, but now the Stranglers were cool. In the Eighties, likewise, only now Aztec Camera were cool. But somewhere along the way, the massed ranks of intellectual rock critics decided to go all gooey and start metaphorically lobbing their Y-fronts at Tom. To justify this, they all agreed he'd "reinvented" himself in 1988 by singing "Kiss", a song by Prince, or maybe it was "Prince", a song by Kiss. But the "Kiss" thing was a fad, and, when it faded, there was Tom still singing the same old Les Reed songs that had catapulted him to fame - and which turned out to have a cool all of their own.

In fact, the striking thing about Tom Jones is how un-reinvented he is. God knows, they've tried to reinvent him: In the late Seventies, Gordon Mills signed Tom to a five-album country-music deal without first taking the trouble to inquire of Tom whether he liked country music. By the third album he was not in a good mood. What he really likes to do, now as then, is just open up and bellow::

What's New, Pussycat?

Whoa-o-o-o-o-oah!

And:

She's A Lady

Whoa, whoa, whoa

She's A Lady

Talkin' about mah little lady...

And of course the original and best:

Why can't this crazy love be miiiine?

Whoa-o-o-oh-oh-oah!

Like everybody and his Auntie Gladys, these days Tom is a judge on a reality show. Here he is, just last year, being cajoled into giving it a bit of Welsh welly one more time:

By the way, do you say "un-u-zhu-ul", as the song does? Or do you say "un-uzh-u'l" tri-syllabically? Most people, in my experience, do the latter. But, oddly, one of the few people I've ever met who says "un-u-zhu-al" is Tom Jones. At first, I thought he enunciated thus in order not to be inconsistent with his signature song. But actually he's a very polysyllabic guy and not one to elide: Half the anecdotes he recounts end in an extremely Welsh "Un-bee-lee-va-bull!" Somewhere along the way Gordon Mills and/or Les Reed made the decision to set the word "unusual" on four notes, not three, and I wonder if that was due to Tom lying around the flat all day long, and, when you asked him if he wanted fish'n'chips again tonight, he'd reply, "No, thanks, boyo. I fancy something more un-u-zhu-al."

Gordon Mills died in 1986, his last few years plagued by a landmark lawsuit from his client Gilbert O'Sullivan, who claimed (successfully) that he'd been suckered into a hugely disadvantageous contract. Les Reed survived for another third of a century and lived to see some of his songs fade away as forgotten pop novelties of the day but a select group of his very best survive and prosper and, as in the clip above, earn genuine praise from musicians young enough to be his grandkids. And in the music business that kind of endurance really is unusual. Rest in peace.

~As Mark mentioned, his essay on Les Reed's "Delilah" can be read in his book A Song For The Season, personally autographed copies of which are available from the SteynOnline bookstore - and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter the promo code at checkout to enjoy the special Steyn Club member discount. Our Club is fast approaching the start of its third year - and although, as we always say, club membership isn't for everybody, it does help keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Sunday song selections. And we're proud to say that this site now offers more free content than ever before in our sixteen-year history.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's an audio Book of the Month Club, and a video poetry circle, and a live music club. We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have other benefits. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we also have a special Gift Membership. More details here. And please join Mark and his guests on the Second Annual Mark Steyn Club Cruise, where we'll enjoy among other things a live-performance edition of Steyn's Song of the Week.