The news of this week was summed up in a phrase: Habemus papam. The election of a new Pope was major news for the world's 1.4 billion Catholics, of course, but the internal workings of the Vatican hold a strange, almost universal appeal, and even after two millennia the papacy is appreciated as a political institution as much as a religious one.

Everybody, Catholic or not, suddenly had an opinion about the candidates and the factions fighting over each ballot behind the locked door of the Sistine Chapel, and the most confident analyses were, as ever, offered by non-Catholics – agnostics and atheists of every degree sharing expert opinion about a religion they're happy to ignore or mock in the long years between conclaves. In the end the winner was a dark horse among the papabile and not one of the front runners confidently listed when the week began.

People claimed they'd been watching a recent Netflix film based on a novel by Robert Harris to learn about how papal conclaves work. (Even more troubling was a rumour that cardinals in Rome had been watching it.) It would have been the most obvious choice for this week's film, but the "shock twist" ending is well known and I'd rather write about another, much older film, about another papal conclave, made back before movies about the Catholic Church were more basically sympathetic.

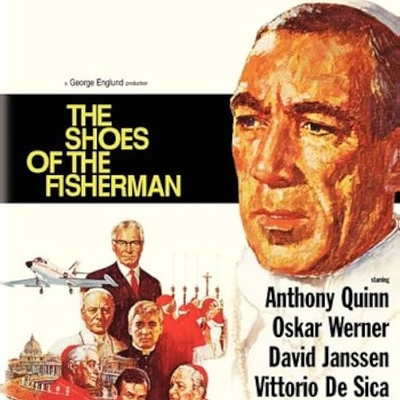

The Shoes of the Fisherman came out in 1968, at the end of a long cycle of Hollywood films that didn't just obey the old Production Code's insistence on treating religion respectfully; they were imbued with a fascination with the rituals and mysteries of the Catholic Church and made with the certainty that there was a potential audience of millions, many of whom would hear their most persuasive review coming from the pulpit on Sunday.

There were films like The Song of Bernadette and The Nun's Story, The Keys of the Kingdom, The Miracle of the Bells, Lilies of the Field and Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison. Gangster films like Angels with Dirty Faces, musical comedies like Going My Way and thrillers like I Confess treated Catholics and what they believe seriously. It would be years before the tone shifted to demons and exorcists, Dan Brown's secret cabals hiding sinister histories, priestly abuse and nunsploitation.

The Shoes of the Fisherman is a widescreen epic nearly three hours long, with an overture, an intermission and an entr'acte. The first shot is a blindingly white screen with a tiny, tracked vehicle struggling to cross the screen. We finally get a close look at it when it arrives at the gates of a prison camp – a Siberian gulag where a prisoner (Anthony Quinn) identified with his name and number is summoned from his shovel in a deep pit.

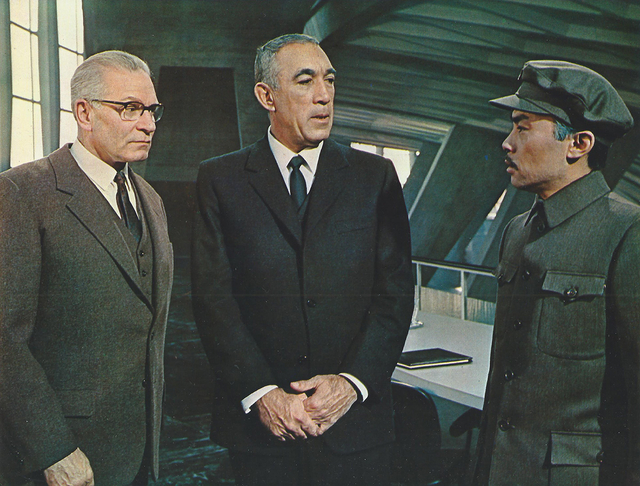

The prisoner is taken to Moscow where we learn that he has spent nearly twenty years in the gulag, one of countless victims of Stalin's paranoia (or so a well-read viewer would presume). His name is Kiril Pavlovich Lakota and he was once the archbishop of the Ukrainian city of Lviv. He has been summoned from prison exile by Kamenev (Laurence Olivier), a KGB agent who was once his torturer, and is now the Premier of the Soviet Union.

Kiril's release has been negotiated by the Vatican, though Kamenev hints that he might have his own reasons for setting him free. Whatever they are, Kiril is placed in the care of Father Telemond (Oskar Werner) and put on a plane to Rome, where he meets the Pope (John Gielgud), who informs him that he is now a cardinal – an honour Kiril tries and fails to turn down.

At this point the action cuts away to a high society party where we're reintroduced to Faber (David Jannsen), an American TV journalist in the authoritative Murrow/Cronkite mould who's in the sticky situation of being at the same party with Ruth (Barbara Jefford), his wife, and his younger mistress Chiara (Rosemary Dexter). Their little melodrama comes with Jannsen's role as narrator, delivering exposition and explanation to the TV camera and to us.

A more crucial subplot is that of Telemond, an anthropologist and theologian and the author of ten books that remain unpublished because he's under investigation for heresy by a tribunal led by Cardinal Leone (Leo McKern). He also admits to Kiril that he's suffering from a terminal illness and is desperate to get the prohibition lifted from his life's work before it ends.

The crux of what the tribunal considers something "truly dangerous" that "challenged the faith" is a variation on the sort of question that self-defined rebels in Catholic school would pose to the unfortunate priest tasked with teaching religion – in essence, if God is good why is there evil in the world? It seems like a profound question when you're sixteen and running off the fumes from George Carlin records and Kurt Vonnegut books, but the movie spends considerable time with Werner's Telemond trying to both explain and defy his inquisitors, over two long scenes, the first of which abruptly ends with news that the Pope has died.

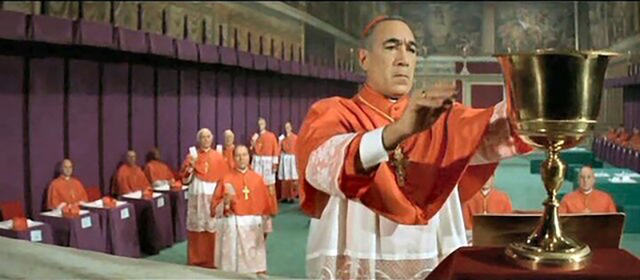

This sets in motion the conclave that makes up the main part of the first half of the film. We get to see – and have explained by Jannsen – the rituals that take place as soon as a pontiff dies: the sealing of his chambers, the breaking of his seal and his ring. And, of course, the considerable logistical effort that goes into hosting a conclave, from building accommodation for the cardinals in the ancient halls of the Vatican to the moment the voting cardinals are locked away to begin deliberation.

The Shoes of the Fisherman was based on a novel by Morris West, an Australian writer and onetime Christian Brother who had a series of bestsellers (The Devil's Advocate, The Clowns of God, Lazarus) that explored faith and political power. The book had the luck to be published on the day Pope John XXIII died, sending it rocketing up the bestseller charts and guaranteeing options for a movie adaptation.

MGM bought the rights with Anthony Quinn attached to play Kiril early in pre-production. Anthony Asquith (The Browning Version, The Importance of Being Earnest) was set to direct until he became ill (he would die in early 1968) and was replaced by another British director, Michael Anderson.

The producers were fortunate in that the previous decade had seen the deaths of two Popes and two conclaves, providing plenty of stock footage to mix in with their Roman location shooting and in studio recreations of locations like the Sistine Chapel, since the Vatican had offered some technical assistance but no filming permits.

Telemond was based on Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the Jesuit and paleontologist whose attempts to reconcile religion with science saw several of his books condemned by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, though his work was never put on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (still in existence during his lifetime) and Joseph Ratzinger – later Benedict XVI – praised many aspects of de Chardin's work.

He's considered far from controversial today, and audiences who sit through both of his scenes with his inquisitors from the Curia will wonder just how all of this graduate studies common room semantic jousting is judged so full of troubling errors that Telemond is prohibited from publishing.

Kiril himself is based on two Ukrainian Catholic bishops, Josyf Slipyj and Hryhorij Lakota. The latter died in the gulag in 1950 but Slipyj was released from the camps the same year West published his book, thanks to pressure from John XXIII and U.S. president John F. Kennedy.

West had a serendipitous touch with his books; the idea of a Pope from behind the Iron Curtain was outlandish in 1963 but fifteen years later Karol Wojtyla from Poland became John Paul II, and The Clowns of God, his sequel to The Shoes of the Fisherman, tells the story of a Pope who resigns from his office – thirty-two years before Benedict XVI would do the same.

Meanwhile at the conclave the front runners – McKern's Leone and Cardinal Rinaldi, played by the great Italian director Vittorio De Sica, complain to each other that age has put them within reach of Peter's throne but deprived them of the vitality to be potentially great pontiffs. "What am I now?" Leone observes bitterly. "A walking encyclopedia of dogma."

Seven votes produce no consensus, but Kiril impresses his fellow cardinals during their long seclusion. It's a strange scene – he admits that he once came close to murdering a guard in the gulag, and when asked if he condemns his actions, doesn't rule out violence as an option in an unjust world.

But it makes an impression and Kiril is acclaimed by his fellow cardinals, who converge on him in the middle of the Sistine Chapel like a lynch mob while he begs them to reconsider. He's persuaded to accept and puts on his vestments in the Room of Tears before being introduced to the throng waiting in St. Peter's Square as Pope Kiril I.

But he quickly discovers that he's a prisoner of the office and contrives with his valet (Arnoldo Foà) to escape the Vatican City dressed as a priest. He ends up in the Jewish Quarter where he meets Faber's wife Barbara, a doctor, making a call on a dying man. Kiril demonstrates his ecumenicism by saying Kaddish with the man's family and friends, telling Barbara that he learned the prayer from a rabbi in the gulag.

In the meantime the gambit that Kamenev set in motion by releasing him has paid off better than the Premier hoped, which is fortunate as the Chinese, suffering a famine after a drought, are massing their armies on the borders of Hong Kong, Vietnam, Thailand and Russia, preparing to invade to seize the resources to feed their people. Kamenev sends the Pope a gift – a box containing sunflower seeds and earth – along with Bounin (Frank Finlay), and emissary and one of Kiril's torturers in the Lubyanka, who tells him he might be the only man who can stop what will quickly escalate into World War Three.

Kiril ignores all of his advisers except for Telemond and flies to meet Kamenev and Chairman Peng (Burt Kwouk, who played Cato opposite Peter Sellers in the Pink Panther films). The Chinese leader doesn't imagine the Pope can do anything to help his starving people or stop the inevitable conflict, but we see Kiril fly back to Rome possessed by an idea.

The Shoes of the Fisherman is a strange, uneven, ultimately unsatisfying film. Director Michael Anderson had a decent career, making films like The Dam Busters (1955), the first movie version of Orwell's 1984, starring Edmond O'Brien and Michael Redgrave, and the star-studded adventure epic Around the World in 80 Days – all in two years. He made a curious spy film, The Quiller Memorandum, just before The Shoes of the Fisherman, and by the mid-70s he'd be responsible for Logan's Run and Orca.

It's a pastiche of a career, and it's no surprise that The Shoes of the Fisherman goes all over the place. The opening scenes in the Siberian wastes looks like second-tier David Lean (Dr. Zhivago had been released just three years earlier) while Kamenev's Presidium headquarters, with its giant control panels and big screens, concrete walls and modernist furniture comes off as a wide miss at recreating one of Ken Adams' villain's lairs in the James Bond films.

Quinn's Kiril is similarly inconsistent. The actor's trademark is his unstoppable, explosive vitality, and we get glimpses of this hunger for life and experience in just two scenes where he's being driven through Rome to the Vatican and then wandering the city after escaping his palace. For the rest of the film, however, he acts as if the weight of his vestments are smothering him.

Back at the Vatican and on the verge of his papal coronation, Kiril tells Leone and the other cardinals that he wants to respond to the revolutions that are sweeping the world with a new Marxism – a "new revolutionary idea". He threatens to abdicate on the spot if he doesn't get their support and ironically it's Leone – the defender of dogma and tradition – who tells his fellow cardinals that "This is Peter – and I stand with him."

Anderson's camera lavishes endless shots on the ritual and luxury of life at the Vatican, and cuts stock footage of recent coronations with equally magnificent recreations of this highest of high masses to impress on us the resources necessary to create the Vatican's spectacle of spiritual magnificence.

We watch Kiril carried aloft on the papal litter to be crowned Pope, and then, on the balcony overlooking the crowds in the square below, he takes off his papal tiara (modeled on the one worn by Paul VI) and announces that the wealth of the Church – "money, holdings, land, buildings and works of art" – will be sold for the relief of the Chinese people.

"If the Church has to strip itself down to poverty, so be it," he tells the crowd, who respond with a growing cheer.

It's probably the most extreme version of the Liberation Theology that surged through the Church after Vatican II, taking root most deeply in Latin America (and influencing the late Pope Francis). There had actually been famine in China when West wrote his book, killing 20 million people, but it wasn't caused by drought but by Mao's utter inability to understand agriculture, economics or society, and in any case China never resorted to invading its neighbours in the Cold War catastrophe scenario West imagined.

It's hard not to watch the film and speculate that Kamenev's gambit paid off handsomely, with one enemy of the Soviet Union willingly bankrupting itself to placate another one. And while there are plenty of people – Catholic or not – who'd support an "everything must go" Vatican yard sale in support of an unprecedented humanitarian aid program, it would be an enormous shame if all the treasures of the Church were to disappear into the black box that is the international art market, fed into its vast machinery for money laundering.

While The Shoes of the Fisherman was the sixth most popular film in Morris West's Australian homeland, it was a box office flop along with MGM's other big picture of the year, Ice Station Zebra, and led to the chairman of the studio resigning. It did get Academy Award nominations art direction and Alex North's score, and though there have been no critical reappraisals of the picture in the nearly sixty years since its release, apparently Richard Nixon was a fan: it was the first film he screened in the White House cinema.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.