Like so many westerns after Tex Ritter had a hit with the theme for High Noon, The Lonely Man (1957) starts with a cowboy tune sung by no less than Tennessee Ernie Ford. "The world looks empty to a lonely man," Ford sings, "as he rides an endless trail." It's a "hopeless" world "as he drifts from place to place." The credits roll over the silhouette of this lonely man on horseback, a tiny figure in a vast wasteland captured in Paramount's VistaVision.

American westerns in the '50s were probably the pinnacle of the genre, at least if you go by the best of the decade – a subjective list, for sure, but one that will contain High Noon, The Searchers, Shane, Rio Bravo, 3:10 to Yuma and Winchester '73, and can be expanded to include anomalies like Giant, Johnny Guitar and Bad Day at Black Rock. If you stop squinting so hard the list could expand to Budd Boetticher's Ranown Cycle and The Furies, among dozens of b-westerns, fan favorites and obscurities.

The Lonely Man likely wouldn't make the list, mostly because it's a real obscurity despite its star-studded cast, and probably because its director, Henry Levin, managed to avoid being called an auteur and had a career that would challenge programmers at TCM looking to fill up a coherent weekend. That's a shame, and it makes you wonder just how many other hidden gems are hiding in the used DVD bins.

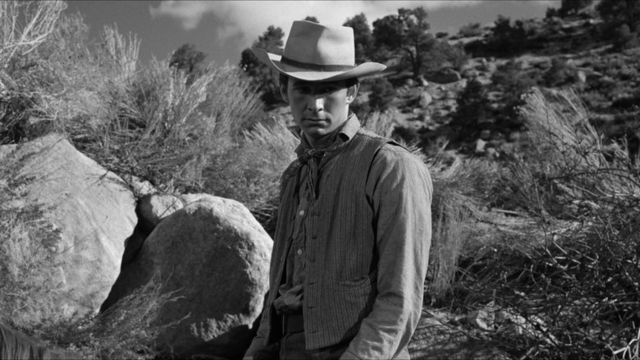

The lonely man is Jacob Wade (Jack Palance), an outlaw and gunman of considerable infamy across the territory. He enters a saloon in a town where the local sheriff knows him well and gives him till noon the next day to finish his business. It takes him much less time than that; he's looking for his son, Riley (Anthony Perkins), who happens to be holding up the bar in the same saloon. Jacob buys the young man a drink, which is eagerly accepted until he introduces himself, prompting the young man to throw the drink back in his father's face with a single, almost unconscious swing of his arm.

Jacob asks where Riley's mother is; the young man takes him to the edge of a steep cliff and says she's been at the bottom of the canyon for five years, unable to live with the shame of being a pariah in their community, the abandoned wife of a killer. The family home is now a dusty shack and Riley, with nothing to lose, accepts his father's offer to head out with him if only to serve as a reminder of how he ruined their lives. On the way out Jacob burns down the homestead.

Jacob has no shortage of enemies, among them King Fisher (Neville Brand), a casino proprietor who has been nursing himself back to health after Jacob left a bullet in his chest during a gunfight. Barely more than an outlaw himself, he has Willie (Elisha Cook Jr.) out looking for Jacob, with a plan to challenge him to a re-match using Faro (Lee Van Cleef), his right-hand man, as a ringer to get in the first shot while Jacob's attention is elsewhere. After laying this out for the audience so early in the film, Levin is not only obliged to deliver on this at the end but give us a good reason to sit through the next eighty minutes.

Jack Palance had come a long way fast since his movie debut as the stone-faced villain in Elia Kazan's Panic in the Streets (1950). This son of a coal miner and onetime club boxer had used his G.I. Bill money to study journalism and then drama at Stanford, before understudying and then replacing Marlon Brando in the Broadway production of A Streetcar Named Desire.

A prominent role in Halls of Montezuma (1951) led to co-starring with Joan Crawford in the noir Sudden Fear (1952). This got him his first Oscar nomination, followed by another for his role as the hired gunman in Shane (1953). He played Indians, soldiers, heavies and tragic noir heroes in films like Second Chance, I Died a Thousand Times, Arrowhead and Attack! He played Attila the Hun in Douglas Sirk's Sign of the Pagan.

Palance had a pretty great career in the end, moving between Hollywood and Europe and between film and television to wherever the work was, until his turn as a parody of his bad guy image in the western comedy City Slickers (1991) gave his career a last act revival that most actors would envy. In 1957, however, he was still riding on his first wave of success, refining that image as "The Meanest Guy that Ever Lived" – the title of a song Palance wrote for a country music album he released on Warner Bros. in 1969.

Anthony Perkins could not have been any more different from Palance, which does a lot to underline Riley's resentment of his father. Perkins, with the support of his emotionally overwhelming mother, had theatrical ambitions from childhood, and like Palance made his reputation on Broadway when he replaced John Kerr in a production of Tea and Sympathy directed by Elia Kazan.

He made his film debut in The Actress, George Cukor's adaptation of Ruth Gordon's memoir of her early life and starred with Gary Cooper in the Civil War drama Friendly Persuasion, which led to an Oscar nomination and a contract with Paramount. The studio started a publicity campaign to make Perkins a teen idol; he would put out records as "Tony Perkins" on Epic and RCA and made four films in 1957: Fear Strikes Out, a baseball picture, Tin Star, another western co-starring Henry Fonda, and This Angry Age, an Italian co-production directed by Rene Clement.

Perkins could compare notes on the teen idol business with Tab Hunter, with whom he was in a relationship at the time. It's easy to cite Perkins' sexuality as the reason why he cuts such an enigmatic figure across his pictures, and though it would be another three years before his signature role as Norman Bates in Psycho, he exists at cross purposes with his estranged father and the general setting in The Lonely Man, like an angsty theatre kid that wandered into the wild west.

While Jacob is earnest about leaving his outlaw past and making amends with his son, his reputation is an obstacle. Like so many westerns of this period, The Lonely Man is set near the end of the frontier, when civilization is trying to stamp out lawlessness; while passing through a town, Jacob tries to buy a blacksmith's business to go straight and create a place somewhere for himself and his son, but the local sheriff recognizes him and runs both father and son out of town.

When Riley gets sick on the trail he decides to return to the only other home he ever had – the ranch he shared with Ada (Elaine Aiken), a woman who played piano in King Fisher's casino and the cause of the gunfight that Jacob won. He ends up reuniting there with Ben (Robert Middleton), a member of the last gang Jacob led, now disbanded. Together they set out to capture and break a herd of wild mustangs led by a stunning white stallion – a quest that finally creates a bond between father and son.

Levin invests a lot in these sequences, which haul a lot of metaphorical cargo; while most of the scenes between Jacob and Riley unfold without any musical cues, silence underlining the awkwardness between them, Van Cleave's soundtrack bursts from the screen while the cameras follow the pursuit of the white mustang through the landscape around Lone Pine, California, including Mount Whitney and the Alabama Hills – one of the most photographed settings in Hollywood westerns since the silent era.

It turns out that King Fisher isn't the only enemy set on ruining Jacob's last chance at going straight when the remnants of his last gang, led by Blackburn (Claude Akins) turn up looking for horses to help them outrun a posse. They try to take Riley hostage but only force Jacob into a showdown that he wins with Ben's help. For a brief moment the four of them seem like they could create a refuge for themselves.

Jacob had given the ranch to Ada before he left in search of the family he left behind, but returns with a son that, as Riley himself notes, is closer to her age. The attraction that grows between Riley and Ada isn't technically oedipal – let's call it quasi-oedipal – and Leven never really lets it become a conflict between father and son. It becomes a sore point for Jacob's friend, Ben, and sets off a brawl between the boy and the portly outlaw while they're supposed to be finishing a corral to capture the white mustang and its herd.

Jacob sends his friend away, but not before Ben tells Riley that his father never really left his mother – that she had refused to go with him when a gunfight that took a deputy's life sent Ben and Jacob on the run again. She was apparently too "used to her comforts" to imagine life on the run with her child. ("She wasn't strong enough for pioneering," Jacob tells him.) Ben rides away, only to run into King Fisher and Faro on the trail, who test out their two-gun ambush on him.

Henry Levin began his career as an actor on Broadway before taking on a job as a dialogue director at Columbia during the war, which led to directing pictures like Cry of the Werewolf and I Love a Mystery, both starring Nina Foch. He became one of the studio's top directors before moving to Fox, and though most of the films he made during this period are barely remembered, he had hits like Jolson Sings Again, the top-grossing film of 1949. Levin was the kind of director studios love, though – a reliable journeyman who made few demands; in the same year that he made The Lonely Man he helped Fox launch Pat Boone's movie career with April Love and Bernardine.

He'd direct Boone again alongside James Mason in an adaptation of Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth, a critical and commercial hit that got three Academy Award nominations. He'd have another hit in 1960 with the teen film Where the Boys Are and directed real life couple Bobby Darin and Sandra Dee together in If a Man Answers (1962). The ensuing decade included a collaboration with George Pal (The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm), an adventure epic (Genghis Khan) and Kiss the Girls and Make Them Die, a James Bond spoof shot in Rio and starring Mike Connors, for which I've always had a soft spot after coming across it on TV one Sunday afternoon as a boy (while completely missing the humour).

Levin's last film was Scout's Honor, a 1980 TV movie starring child actor Gary Coleman, though he died of a heart attack while on location. For years he was remembered for his biggest hits – films like Jolson Sings Again and Journey to the Center of the Earth – though western fans who've come across the two reissues of The Lonely Man on DVD and Blu-ray have created a new consensus that it might be his best film.

Levin certainly got one of the best early performances out of Palance here – essential in a film where his Jacob is just one of many bad men filling the screen, but the only one concerned with redemption. The actor makes the outlaw's regret palpable in every scene, painfully grasping at every hopeful moment with believable desperation.

In his Encyclopedia of Western Movies, Phil Hardy calls The Lonely Man "an interesting minor western" and one of a tradition of father-son westerns, adding that while most of these pictures concentrate on the son "trying to overcome the dead weight of the past" Levin's film makes the father's struggle for forgiveness and longing to re-create the home he shattered the focus.

The stakes for Jacob increase when we learn that he's slowly going blind – a condition that would be debilitating and likely terminal on the pitiless frontier even if he weren't a gunslinger. He's in a race against time, not just with his physical deterioration but to get his son into a place where violence and murder are options where the law is nominal; Levin makes a point of never putting a gun in Perkins' hands, or having his father give him a crash course in shooting.

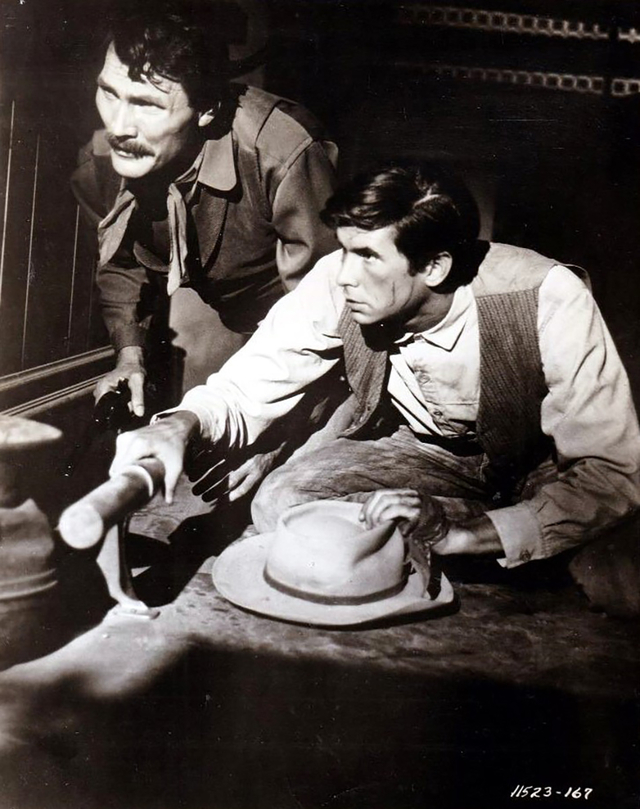

The inevitable final meeting with King and his gang is set at night, in his saloon, where the vengeful gambler has prepared the ground in advance. The only way Jacob can make it an equal fight is to literally shoot out the lights and rely on Riley to guide his aim. You wonder what a director like Ford or Wellman might have done with these situations, but Levin is no auteur, and they play without an excess of context or style.

If Levin allows himself any stylistic quirk in The Lonely Man, it's the way that scenes frequently end with a quick fade to black even before the dialogue is finished. It's as if he's impatient to bring Jacob's story to its conclusion.

The end, when it comes, is exactly as we would have predicted it an hour earlier; Jacob's fate was a chain pulling him to the place where either fate or bad choices had him consigned, as in so many westerns of this period, ambitious or humble. Redemption might be sought and forgiveness earned but the moral laws of the classic western are unequivocal about bad men being brought to a place of judgment.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.