A really influential film, seen decades after its influence has percolated into dozens (if not hundreds) of films and redefined a whole genre, can elicit a feeling of déjà vu. Who knew that an ultra low budget horror b-movie would spawn a subgenre that persists to this day (Night of the Living Dead) or a gang picture originally imagined as a western, marketed to dopey teens (The Warriors) would be copied over and over with immensely larger budgets for decades.

Then there were the films that looked like game changers from their opening weekend. Anybody leaving The Godfather in the spring of 1972 knew that gangster films would never be the same again, and the years after the release of Dr. No were filled with copies or spoofs of what everyone now knew a spy movie should look like. Finally there was the watershed moment that was 2001: A Space Odyssey, which upped the game for special effects and made sci fi pictures break for intellectual ponderousness and away from corny camp.

British gangster films never seemed as grand as their American counterparts, perhaps because the stakes never seemed comparable – what was running the rackets in a seaside holiday town (Brighton Rock) compared to doing the same thing in Chicago? If you lived in working class areas of London, Birmingham, Liverpool or Glasgow you knew exactly how established and pervasive organized crime could be, but to Americans films like The Lavender Hill Mob and The Ladykillers were all you needed to know about British gangsters.

But something changed in Britain in the '60s that made a film like Get Carter possible. Director Mike Hodges recalled that up until then the British thought their criminals were "quite nice in comparison to the horrible American ones – 'Move over. Guv, it's a fair cop" – and they didn't carry guns. The British also thought their police were wonderful. I remember having violent arguments with my parents, saying that the British police were just as corrupt as any other police force."

Writing about the turning point in Your Face Here: British Cult Movies Since the Sixties, Ali Catterall and Simon Wells say that "the Kray/Richardson trials in 1969 prised open a can of worms from which the reality of gritty gangland violence and corrupt policing would finally emerge, culminating in early retirements for several high-ranking officers a few years later. Far from cheeky folk heroes, the East End's 'Merrie Men', they were now labelled sadistic killers."

The film begins with a slow zoom in on Jack Carter (Michael Caine) looking out the window of an apartment building at night. He's a gangster in the employ of the Fletcher brothers, Gerald (Terence Rigby) and Sid (John Bindon, who was cleared of stabbing a London gangster to death after actor Bob Hoskins appeared at his trial as a character witness); he's also having an affair with Gerald's girlfriend Anna (Britt Ekland) and plans to escape to South America with her, though it will take a while for the film to fill us in on their plan.

Right now, while his bosses flip through a slide show of pornography and crack wise, he's being counseled not to go back home to Newcastle to look into the death of his brother Frank.

"The police seem satisfied," they tell him.

"Since when was that enough?" Carter replies.

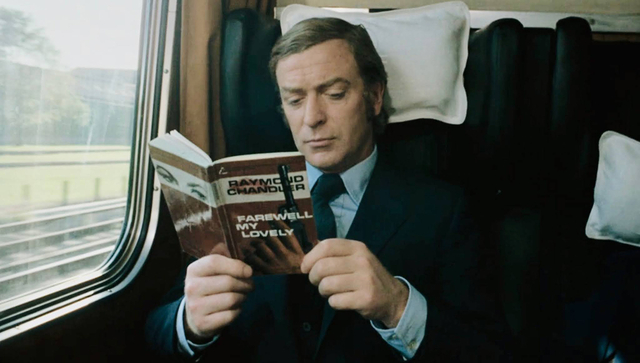

The credits roll over his train journey north in a first-class compartment. We get a cursory sketch of Carter; he's fastidious and concerned about his health, administering drops in the washroom and regularly taking two little black pills. On the soundtrack we hear music by Roy Budd, a jazz musician from South London whose mesmerizing score for the picture (recorded for just £450) would become sought after by rare groove collectors when it was released on Pye (though the Japanese Odeon pressing, with extended tracks, would be the real holy grail).

It's obvious that Carter is being clocked from the moment he walks into a bar across the street from the train station. A Land Rover full of men tails him as he books a room at a bed and breakfast and then visits his brother's tawdry little terrace house, where the dead man lies in his coffin alone until his brother arrives to sit vigil overnight before the funeral, shaving with his electric razor over the open casket.

We meet what little family Carter has: there's his niece Doreen (Petra Markham), who may or may not be Carter's daughter after a brief affair with Frank's (now long gone) wife. And there's Margaret (Dorothy White), Frank's girlfriend, an unapologetic tart who claims that Frank got drunk and made a scene after she told him she wasn't going to leave her husband, just before driving his car into the Tyne.

And then there's the extended criminal "family" in which Carter is a member in good standing. There's Albert (Glynn Edwards), an old friend, and Eric (Ian Hendry), an old enemy, as well as Con (George Sewell) and Peter the Dutchman (Tony Beckley), two colleagues from London sent by the Fletchers to bring him back home.

There's Cliff Brumby, a local businessman who dominates the slot machine business in the city, a semi-criminal who hides behind the façade of a seedy but technically legal business. Tailing Eric from the Newcastle Racecourse leads Carter to Cyril Kinnear, the big boss of the city's criminal underworld, played with bloodless menace by playwright John Osborne (Look Back in Anger, The Entertainer, as well as the screenplays for Tom Jones and The Charge of the Light Brigade).

By the time the picture is over Carter will kill most of them.

Get Carter began life as Jack's Return Home, a 1970 noel by Ted Lewis, a onetime illustrator who worked on the Beatles' Yellow Submarine. Producer Michael Klinger, who began his career making soft core pornography (Naked as Nature Intended, That Kind of Girl, The Yellow Teddy Bears) and moved on to produce Roman Polanski's Repulsion and Cul-de-sac, was hired by MGM's British office during a transitional period to make some pictures (co-financed by EMI) as an olive branch to the film unions who were hurt by the closure of MGM's studios at Borehamwood.

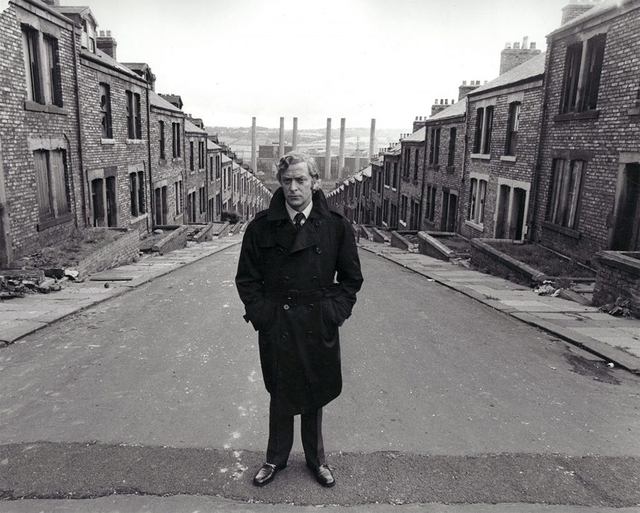

He bought the rights to Lewis' book and in turn hired Mike Hodges, a young director who began his career as a teleprompter operator before making dramas for Granada, ABC and Thames Television. Get Carter would be his feature debut, and he wanted to shoot it on location in the northeast of England – port towns like Hull, Grimsby and Lowestoft whose grittiness had impressed him when he'd done his national service on minesweepers in the Royal Navy.

Discovering that many of those places had their grimy character altered by slum clearances and urban redevelopment, he settled on Newcastle after visiting the city on a location scout, on his way to North Shields. "Visually," he recalled, "it was absolutely extraordinary." He researched the city's organized crime scene and was fascinated by Vincent Landa, a fruit machine distributor who fled the country after his brother and an accomplice were imprisoned for the murder or a business rival.

Hodges ended up renting Landa's former home, Dryderdale Hall, as Kinnear's mansion in the film. The gangster had left his possessions behind, and the art director for the picture "kept bringing me all these incredible things he'd found, including two children's drawing books...In particular, there were two pages in which an adult had written 'Cain and Abel, Cain and Abel, Cain and Abel"...It must have been written over twenty times in big letters and the implication, I would have thought, was to do with Landa's brother."

Writing about the film in his first (and in my opinion best) autobiography, What's It All About?, Caine says that he made the film in partnership with Klinger, though his name appears nowhere in the credits. Caine was unhappy with "the tradition in British films up until then ... that gangsters were either very funny or Robin Hood types, stealing from the rich and giving to the poor. Ot a realistic portrait, as I think you will agree."

Early on in filming a conflict developed between Caine and Ian Hendry, whose career had begun with promise; in the first series of The Avengers he had top billing over Patrick Macnee's John Steed, but he left the show for a movie career that, when it didn't develop as he hoped, turned him into an alcoholic. Klinger and Hodges both remember him showing up for a meeting drunk with a chip on his shoulder about Caine.

"It became apparent that (Ian) really hated Michael because he was such a big success. It was a smouldering situation and I thought 'How am I going to handle this? We hadn't even begun shooting yet.' Michael said to me, 'Don't worry, he hates me and that's good. I'm going to make this work for the film.' He really did, that edge between them comes over very well."

But with Caine in the lead, the studio started pushing Klinger and Hodges to cast bigger names in the cast. Telly Savalas, Joan Collins and Barbara Parkins of Peyton Place were suggested, and Hodges threatened to quit, but one big name that did end up in the picture was Britt Ekland, who barely shares the screen with Caine for more than a moment, and only really interacts with him during what can only be described as the first phone sex scene in the movies. Hodges compensated for this studio interference by filling the screen with local actors and characters from Newcastle's criminal demimonde.

A major sex symbol after The Ipcress File, The Italian Job and especially Alfie, Caine's Carter isn't too busy with revenge to get a couple of in-person sex scenes, one with Edna (Rosemarie Dunham), his landlady at the bed and breakfast, and another with Glenda (Geraldine Moffat), a gangster moll who saves his life but seems to be playing both sides in the budding gang war brewing in Newcastle.

Like many movies shot on location, Get Carter is an accidental documentary, scooping up vignettes of real life that immensely help set the atmosphere. There's a scene with a singer in a local pub – an older woman (Denea Wilde) who delivers her version of Burton Lane and Ralph Freed's "How About You?" by flirting with men in the crowd and gets tackled by an angry girlfriend for her troubles.

While in bed one morning with Edna, Carter is woken up by a marching band, the Pelaw Hussars, one of the "juvenile jazz bands" that were popular for a couple of decades in the industrial northeast and mining towns of the Midlands and South Wales. They blast out "When the Saints Go Marching In" and "Auld Lang Syne" on kazoos while a naked Carter holds Con and Peter the Dutchman at bay with a shotgun.

And finally there's a scene where Carter pursues Kinnear's errand boy Thorpe through the Oxford Galleries disco after seeing off a car full of thugs. There's a single brief shot that's wildly evocative of youth culture in the north – a tableau of young women dancing on the spot, their eyes bored as they survey the room, anchored by their purses on the floor next to them.

When Phil Oakey of synth pop group the Human League was looking for new members with a visual edge he and his girlfriend discovered Susan Sulley and Joanne Catherall, both just seventeen, dancing together in a similar scene in a Sheffield disco. The group would record a cover of Roy Budd's theme for Get Carter on Dare, their next record.

Carter discovers some grim business behind his brother's death, but he's a man made for just such dealings. In one famous scene he confronts Brumby in his home one night after the man has had to break up a party thrown by his daughter. The older man tries to push back against the intimidation but Caine delivers one of the film's best lines: "You're a big man but you're in bad shape. With me it's a full-time job."

Carter is implacable and remorseless, capable of any act of violence; if he's reminiscent of any other movie character it's Lee Marvin's Walker in Point Blank, which came out just three years earlier. The film's violence and its lead character's pitiless morality was noticed by critics when the film was released; the London Evening News called it a "revolting, bestial, horribly violent piece of cinema."

In a 1972 interview Hodges reflected that there were "sociologists who don't like the idea that some people are irredeemable, there's no way you can touch them. I am personally terrified of meeting some guy I couldn't talk to, to stop him killing me or doing me over. I can run reasonably well, I could duck, I'm small and could weave in and out, but I couldn't win. I'd have to rely on convincing the guy that he shouldn't hit me. And I've met people you just wouldn't be able to do that to."

The city where Carter has his homecoming is one where the police seem wholly absent and gangsters can have shoot-outs on ferry docks or throw each other off car parks without interruption or consequences. He leaves behind a trail of bodies, some planted with precision like Margaret, who lied about his brother on the night of his death; others like Glenda who put herself in the way of all the revenge and double crosses and ends up in the boot of her car when it gets rammed into the Tyne.

It's a city of betting shops and rotting docks; Caine described it as 'Charles Dickens meets Emily Bronte, written by Edgar Wallace.' It's not a flattering portrait but it was one of the rare appearances of Newcastle in a major motion picture featuring a big star and in 2000 an informal appreciation society had organized a two-hour tour of the filming locations; by 2008 there was a movement to block the demolition of the brutalist Trinity Square Car Park in Gateshead as a piece of the city's cultural heritage. (It was knocked down in 2010.)

The street in Benwell where Carter's brother lived was levelled for a housing estate, and the Long Bar by the train station where Caine is served a pint of bitter "in a thin glass" by a man with six fingers ceased to serve decades ago. But Edna's Las Vegas bed and breakfast is still there in Gateshead though the street has been renovated and remodelled and scrubbed of its working-class character.

The film didn't set the world on fire when it was released in 1971, swamped in Britain by Love Story and netting just a single BAFTA nomination for Ian Hendry. But it did catch the attention of Vincent Landa, the fruit machine king, on the lam in France. Watching it in a Paris cinema with his girlfriend, the authors of Your Face Here described his reaction to seeing his former home onscreen:

"Now, as Caine breezed around the building, Landa began to notice familiar shades of wallpaper and furniture, doors and staircases. 'That's my home!' he murmured to his girlfriend in disbelief. But he was in for a greater shock at the film's denouement. As Kinnear was arrested and driven away by police, a succession of Landa's real-life associates began to fill the screen in a nightmarish procession..."

The film was definitely noticed and while it immediately set the tone for UK cop shows like The Sweeney it had its first palpable echo on the big screen in The Long Good Friday, starring Bob Hoskins as a London gangster trying to go straight as a property developer. It shared the same unflinching violence and portrayal of a world where crime, organized or not, engenders chaos likely to sweep away everyone it touches.

(Let's politely ignore Hit Man, the blaxploitation version of Jack's Return Home made by MGM a year later, and especially the 2000 remake starring Sylvester Stallone, with Caine as Bumbry.)

But Get Carter would ultimately spawn a whole subgenre of British gangster pictures that leaven Hodges' film's grim story with high style and black comedy – pictures like The Hit, Layer Cake, Legend, Sexy Beast, In Bruges, Mr. In-Between, Bull, Gangster No. 1 and much of Guy Ritchie's filmography (Snatch, RocknRolla, Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, The Gentlemen). In the long story of movies, you can spend millions on stars and sets but that kind of influence is priceless.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.