As a place on a map, Bohemia is roughly half of what we call the Czech Republic today. As a neighbourhood or a state of mind it can be found all over the world, in big cities, where it suddenly coalesces in insalubrious districts, flourishes briefly, raises the value of the real estate and then dies off in a flurry of media coverage regretting how these things never last.

When a Bohemia dies it usually leaves behind a few architectural remnants, a historical plaque or two, maybe even a museum, and a venerable and overpriced tourist trap like a café or tavern whose precarious survival inspires even more media coverage describing the long-gone Bohemia's heyday. As a general rule a city's first Bohemia is in some neglected downtown enclave and moves further from the centre until its artistic denizens are finally priced out of that city altogether.

My own hometown, Toronto, has had nearly half a dozen Bohemias in its history, and is a textbook example of how you can use artists as unwilling advance guards for real estate speculation. I spent much of my career as a photographer in one of those Bohemias until I was priced out. Original Bohemias can remain in place for a generation or more, but as a rule of thumb the lifespan of each successive Bohemia gets shorter and shorter until a point when the first article celebrating its attractions marks the moment when it's over.

Hollywood was never a Bohemia, but movie people consider themselves artists and love to tell stories set in some Bohemia in the near or distant past. A Complete Unknown, the recent Bob Dylan biopic, is set in New York's original and archetypical Bohemia, the setting of countless films that are either set there (Inside Llewyn Davis, Next Stop Greenwich Village, Rear Window, Barefoot in the Park) or make a conspicuous visit (Kids, Wait Until Dark, Bells are Ringing, Funny Face). The use of a word like "colourful" to describe a character's neighbourhood in a screenplay is almost inevitably shorthand for some iteration of Bohemia.

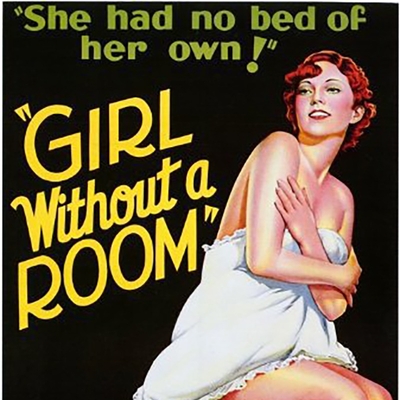

Girl Without a Room, a 1933 pre-Code musical comedy, is set in Montparnasse, in the district of Paris that was home to the original Bohemia. But before it gets there it begins in rural Tennessee, and the moon on the outhouse door of the farm where Tom (Chares Farrell), an aspiring artist, lives with his family and what appears to be a host of boarders.

In a wordless sequence we see Tom signing a painting he's just made of the landscape outside his window before a letter is delivered. He reads it silently before alerting the residents of their country compound, who descend down stairs from rooms and make their way from fields and outbuildings to hear him read the news in rhymed couplets: he's won a scholarship to study art in Paris and in a shot or two he's crossing the Atlantic on the Ile de France and asking directions from a gendarme who steers him away from a decent hotel in a good arrondissement to the artists quarter.

The camera follows a street musician singing a ditty extolling the beauty of living by the Seine, and the melody is taken up by the residents of a boarding house full of artists – an opera singer or two, a room full of bearded musicians slumbering in a single bed. The camera stops in a garret room where Kay (Marguerite Churchill) is lounging on a settee while a man sings a love song – clearly his own composition – on the piano by the skylight window.

Kay is the titular girl without a room, or rather a girl on the verge of losing her spot in the boarding house. She's from Atlanta and came to Paris to be a writer but hasn't had much luck (though she sports a fantastic wardrobe throughout the picture). She darkly muses about how "it's a shame that rivers are so cold" before Tom barges into the room, claiming that he'd knocked but no one had answered.

Moving quickly, Kay negotiates Tom's rent on a room, bundling her own rent into the deal before she presents it as a done deal to the landlord, the General (Gregory Ratoff), a White Russian aristocrat. He gets Tom to pay for lunch as well, to which the General and Vergil Crock (Charles Ruggles), another American painter, invite themselves before Tom ends up being the benefactor of a party for all the tenants and half the street.

So far there's nothing in this depiction of the artist's life in Paris that colours outside the lines of what everybody assumed was true. After the triumph of the Bolsheviks and the killing of the Czar and his family the city was supposed to be full of impoverished White Russian dukes and countesses running restaurants and reading fortunes. And the end of the Great War had filled the city with American expats looking to stretch their dollars in Bohemia and absorb the cultural energy that had begun with the Impressionists.

Back in the U.S. names like Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ezra Pound were celebrities among readers of Collier's, the New Yorker, Cosmopolitan and the Saturday Evening Post. They were a lost generation subsisting on baguettes and absinthe an ocean away from the Babbittry of their hometowns.

The first thing Tom the rube learns is that the realism of his paintings is old hat; Crock tells him about his latest "masterpiece" – an abstract canvas titled "Portrait of a Whistle." "We are of the new school – we paint what nobody sees." He launches into an instructive little tune that explains the rules of abstraction and cutting-edge modernism:

"There was a time the artist's flair was painting ladies who were bare

And sundry bits of landscape and topography

Madonnas prim and maidens prude and little cherubs in the nude

That wasn't art, my boy – that was photography."

Newness and originality are supreme among Bohemian values – or at the very least whatever's new enough to seem like a threat to the cultural status quo, which itself was once a bold assault on the conventional. "Paris" writes Virginia Nicholson in Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900-1939, "was the fount of everything new and modern, not just in the arts but in everyday life. Sisley Huddleston, author of Bohemian Literary and Social Life in Paris (1928), credited Paris with the introduction of, among other things, underground railways, Cubism, Bolshevism, football, tennis, one-way streets, coloured photography, cinemas, cocaine, silk stockings, safety razors, beauty parlours, monkey glands, Freudianism, quick divorces, unnatural vices, wirelesses, Citroën motor-cars, and of course cocktails."

Kay's become a tough nut in Paris but Tom's naivete and helplessness brings out something in her that sparks an attraction, after they're forced to spend the night in his room after her bed is occupied by Crock and a couple of other inebriates at the end of the party. They're about to go out on the town when her former beau Copeland (Walter Woolf King) shows up dressed to celebrate his birthday – a date they'd made while they were still together.

Crock takes the opportunity to fob off Nada (Grace Bradley) on the hayseed. She's the daughter of Walksky (Mischa Auer), patriarch of a group of Russians living in the boarding house, a model and a gold digger under the impression that Tom is a millionaire. Under Crock's artistic tutelage and Nada's companionship Tom decides during a champagne-fueled night out to pour his energies into an abstract canvas, "The Wheel of Life", depicting his new milieu as seen on a bender.

The balance of the film's brisk hour and eighteen minutes is taken up with Tom and Kay's misunderstanding, culminating in him finishing his painting, her decision to marry the dissolute but basically decent Copeland, and the duel Crock is forced to fight with Walksky over Nada's honour (such as it is). It's a pretty thin scrap of a farce, but it's typical of what passed for plots in many pre-Code pictures.

Tom quickly takes on the uniform of the Bohemian artist, sporting a beret, velvet jacket and floppy bow in imitation of Crock. Between Nada and the champagne he's certain he needs to fuel his artistic vision, his scholarship fund is gone by the time he unveils his painting to the crowd in the boarding house, who agree that its incoherence makes it a masterpiece as long as he's paying for the food and drink at the party; only Kay is willing to tell him the truth.

In How to Be Bohemian, a three-part documentary made for the BBC in 2015, Victoria Coren Mitchell explored the phenomenon of bohemian culture from its Parisian origins in the early 19th century. She traces the history of Bohemia from the cheap, slightly dangerous Parisian neighbourhoods where artists lived side by side with gypsies and took on some of their style. The incorrect assumption that all gypsies came from what was once known as the Kingdom of Bohemia gave their movement its name.

Scenes of Bohemian Life, a book by Henn Murger published in 1851, codified the image of the Bohemian for the public, and was further refined when Giacomo Puccini's 1897 opera La bohème, based on Murger's story, became a cultural sensation, revived endlessly. "This version was safer and even more sentimental than Murger's," Coren Mitchell says. "It was a tragic story but a romantic one, boiled into a simple, charming tale with catchy tunes. This was Bohemia to entertain rather than shock the bourgeoisie."

In 1926 King Vidor made a silent film based on Puccini's opera, starring John Gilbert as Rodolphe and Lillian Gish as the doomed Mimi. (Being a silent picture meant that, in essence, it was really based on Murger's book, but by this point it was Puccini's intellectual property as far as the public was concerned.)

Girl Without a Room (also known as No Bed of Her Own) was based on two short stories by journalist Jack Lait and adapted by Claude Binyon and Frank Butler (who would later write the screenplay for The Bohemian Girl, a Laurel and Hardy comedy that was actually about gypsies). It was directed by Ralph Murphy, whose career lasted for three decades but produced nothing that made its mark on posterity.

The film's occasional musical comedy numbers and excursions into rhymed verse vaguely echo the Marx Brothers classic Duck Soup, released the same year, though Murphy's film doesn't have half its energy or recklessness. Even as a pre-Code picture it's far from risqué; the most taboo moment is an early scene where Tom trudges through Montparnasse looking for lodgings and is heckled and propositioned by three prostitutes hanging out of a window.

Like so many pre-Code pictures, its cast is full of names that did not abide by the time Hollywood's golden age began a few years later. Charles Farrell's star was at its height when he was teamed up with Janet Gaynor by Paramount for several pictures, but he would really make his mark as one of the founding figures of the community of Palm Springs. The less said about Grace Bradley's Russian accent as Nada the better.

Mischa Auer had a career that lasted until the late '60s and included roles in pictures like My Man Godfrey, You Can't Take It with You and Destry Rides Again. Charlie Ruggles began acting in films in 1914 and specialized in comic parts in pictures like Trouble in Paradise and Bringing Up Baby, but he's eclipsed by the work of his brother Wesley, a former actor who made his mark directing screwball classics like No Man of Her Own, True Confession and Too Many Husbands.

Marguerite Churchill is the most curious of them all. She'd co-starred with John Wayne in the western epic The Big Trail (1930), his first major role, and in Riders of the Purple Sage (1931) with George O'Brien, who would become her first husband. She's very easy on the eyes but doesn't make much of an impression as Kay. Other actresses such as Carole Lombard and Jean Arthur had similarly underwhelming turns in underwritten parts in pre-Code pictures, but Churchill never found that pivotal role that moulded an onscreen persona.

There certainly isn't much chemistry between her and Farrell's Tom; especially compared to another film released in 1933: Ernst Lubitsch's Design for Living, also set in Parisian Bohemia – a truly transgressive pre-Code picture built around a scintillating menage a trois featuring Miriam Hopkins, Frederic March and Gary Cooper. Churchill's career was effectively over by 1936 and she divorced O'Brien in 1948. Her 2000 New York Times obituary mentions O'Brien and The Big Trail and that she "lived overseas before poor health brought her to Tulsa to be near her son, the author Darcy O'Brien, who died in 1998."

A better script might have given Churchill more to do at the film's climax, when Tom's painting, "The Wheel of Life", wins the grand prize at a modernist salon. But he protests that they've hung it upside down and starts a brawl that escalates into a riot in that fine Parisian tradition; police cars are called out and it all turns into a street party.

Tom's reputation is ruined and he's ready to flee Paris when Nada learns that his money is gone and abandons him. Copeland is blind drunk on the morning of his wedding to Kay and belligerently tells her that she'd be better off with Tom; after she leaves he's suddenly sober and grumbles to Crock that nobody will know about his noble act. The cavalry arrives in the form of a jigsaw puzzle manufacturer who wants to pay for Tom's paintings.

Kay is the only person willing to tell the truth about Crock and the cabal of modernists in Montparnasse. "These people aren't artists," she tells him at the unveiling of his painting. "These are the people who paint what you can't see. Because they can't get anybody to look at it."

They're "the worst crowd of chiselers and phonies" and she admits to being one of them when she took advantage of Tom when she met him. You can only imagine what, say, Jean Arthur might have done with Kay, in a film with a better script and a director who paced his film at speeds less than a brisk trot.

And as fascinating as Bohemia is, Hollywood still casts a baleful eye on modernism as artistic fashion and the world of artists, depicted as so-called nonconformists marching in lockstep. And as Victoria Coren Mitchell notes in her series, Bohemia is always dying, a victim of its success or lack thereof, "Seventy years after Francis Bacon lit up its clubs and bars," she says, "the erosion of Soho's eccentric and independent character, and some say that of Bohemia too, continues unabated, replaced by something bland and generic."

She recalls the hipster moment, when Bohemia seemed to have been finally absorbed and mainstreamed by millennials – "the fraudulent hitchhiker through the country of Bohemia" – reducing rebellion to mere lifestyle at a point when all the rebellions cherished by previous generations of Bohemians – artistic, sexual, political and otherwise – had lost the capacity to shock.

In Among the Bohemians, Virginia Nicholson recalls that writer Arthur Ransome, author of a famous guidebook to Bohemia before the success of Swallows and Amazons, looked back wistfully on his Bohemian youth but "believed that on the whole, Bohemia was for the young. So where do old Bohemians go?"

Nicholson, the granddaughter of Bloomsbury Group leading lights Clive and Vanessa Bell and great-niece of Virginia Woolf, concludes that "the avant-garde has always had to live with the awkward fact that, sooner or later, it creates a following, and that its lonely journey into the unknown can start to seem a little well-trodden after the passage of a few years. Bohemia's greatest achievement may well have been the complete assimilation by today's society of its victories against the establishment."

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.