They're almost all gone now, but there was a time when every city had its art house cinema – some shabby but proud former "nabe" or second run movie theatre whose management had given itself over to screening foreign films and Hollywood classics, often between regular screenings of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Eraserhead and The Song Remains the Same.

They began as a classic middlebrow phenomenon – the private "cinema clubs" that subsisted on memberships, usually to get around censorship laws – and were epitomized by places like Manhattan's New Yorker, which opened in 1960 on the Upper West Side and spawned imitators all over the world, some going so far as to copy the name (like the one in my Toronto hometown).

The art house was built on the critical and (modest but notable) box office success of films like Rashomon, La Strada, The Seventh Seal and Pather Panchali – pictures that were, for American audiences, palpably "foreign" and "intellectual". A notable exception was The Wages of Fear, a gritty 1953 drama by Henri-Georges Clouzot that might have been a classic film noir if it had been made in English, and would influence Hollywood action movies for decades to come.

This might have been helped by the fact that the U.S. release of Clouzot's film was, for many years, a heavily edited version that soft-pedaled its political overtones while tightening up the tense action scenes that make up the ninety minutes of this two-and-a-half-hour picture. I remember seeing it for the first time as a boy when it aired on PBS from Buffalo, tuning in just at the beginning of the nail-biting journey by four desperate men in two explosive-laden trucks, and it captivated me as much as similar, out-of-the-blue late night TV encounters with films like Throne of Blood and Metropolis, a few years before I was even aware of the existence of rep cinemas or art house movies.

I don't know what I would have made of the first hour of the picture; it probably would have gone right over my head, though as a study in squalor and desperation it's indelible and relentless. But this working class boy living with his widowed mom wouldn't have had much in the way of context – not the way I immediately responded to the danger and tension looming over those four men, much as I'd reacted to Dennis Weaver being chased all over a desert highway by that homicidal oil tanker in Duel, Steven Spielberg's 1971 made-for-TV movie, itself heavily influenced by The Wages of Fear.

The film begins with a shot of four cockroaches tied together by a thread, held by a half-naked little boy playing in the muddy streets of Las Piedras – a sun-baked town in some unnamed South American country. The boy is briefly distracted by a man selling flavoured ices, long enough for his arthropodal pets to get scavenged by one of the vultures who stalk the street.

We've seen places like this before in Westerns – a lawless boom town with a name like Dead Man's Gulch created by a gold rush and filled with outlaws and their victims, none more than a few weeks or paces from the burying ground. And like every boom town the social life is based around the watering hole, which is where Clouzot's camera takes us, following that pants-less boy and the flavoured ice seller.

The tables are filled by a crowd of men – a penniless, polyglot group trying to keep the proprietor from banishing them out of their chairs and into the street. But our eye is drawn to Mario (Yves Montand), the most attractive and charismatic of the bunch, defiant in the face of the saloon keeper's hostility, as he carries on an affair with the abject Linda (Vera Clouzot, wife of the director), apparently some sort of indentured servant of the proprietor, who uses her sexually to no real objection from Mario.

The streets of Las Piedras are filled with displaced aboriginals, creole locals of varying shades, and expats from every place, all of whom are desperate to leave. It's a poor, torrid, indolent spot, its economy based on corruption and exploitation. It was once, recently and briefly, destined for greater things but the only evidence of that brief apex is the abandoned frame of a modest skyscraper, left unfinished and looming over the rutted roads.

The only thing breaking up one more purgatorial day is the arrival of a plane at the unpaved airfield. One of the passengers – disembarking just ahead of a man and his goat – is Jo (Charles Vanel) in his white suit and big white hat, who surveys the scene sourly before he forges a quick friendship with Mario, based on their shared ability to whistle Maurice Chevalier's raunchy 1925 hit "Valentine".

Jo, who carries himself like a gangster, discovers that he's like every other white man in Las Piedras, ending up there at the end of a string of bad decisions. They might not have spent much to arrive, but leaving will cost quite a lot more than any of them can earn. The place is like a sink trap, Mario calls it a prison, and he and Jo begin what we'd call a bromance today, and which critics over many decades have reliably (and predictably) described as a repressed homosexual relationship.

Henri-Georges Clouzot was the son of a bookseller, a bourgeois who affected working class manners like most creative children of the French middle class. He began his career as a writer and by the start of the 1930s was working for UFA, the major German studio, translating scripts and lyrics for foreign-language pictures.

With the rise of Hitler and the Nazis to power, his friendship with Jewish producers got him fired from UFA and he returned to France just in time to contract tuberculosis. He spent four years in hospitals, broke and reliant on the charity of family and friends, recovering just as Europe was sliding into war. After the capitulation of France he was offered the chance to direct his own pictures in a French film industry overseen by Nazi occupiers – a decision that would bite back at him just a few years later.

He was an instant success with a comic thriller, The Murderer Lives at Number 21, but his next film, Le Corbeau (The Raven), is considered his first masterpiece, a picture about a town torn apart by poison pen letters that reveal the secrets of its citizens and erupts into suicide and murder. It was hard to ignore the brutal commentary about informants and persecution under German occupation, and it made him no friends with the Nazi government or the resistance.

After the Allied invasion and German retreat, Clouzot was tried for collaboration – a scapegoat in a country full of collaborators and an industry full of jealous peers; his brother Marcel described it as "the revenge of the dunces". Despite protests from Jean Cocteau, René Clair, Marcel Carné and Jean-Paul Sartre he was banned for life from making another film, but the sentence was reduced to two years and in 1947 he made the hit thriller Quai des orfèvres.

Clouzot had a habit of writing parts around or for the women in his life; he featured the cabaret performer Suzy Delair in his first two films, and he met the Brazilian-born Vera Gibson-Amado when she worked on Miquette et sa mère, his fifth film. They tried making a documentary in Brazil during their honeymoon but the government protested him filming in the favelas and upon returning home he was offered the chance to make a film based on a book that he thought reflected his experience in South America.

Georges Arnaud (real name Henri Girard) was an expat in South America who had been imprisoned for the murder of his father, aunt and a servant in their family castle and, upon acquittal, spent his inheritance and left France. The Wages of Fear was inspired by his experience as an expat and Clouzot was so excited by the potential of the story that he began writing his screenplay before he read the book, writing a part in the film for his wife that didn't exist in the original novel.

Jo learns that O'Brien (William Tubbs), an old colleague with whom he ran contraband before the war, is the boss of the local headquarters of the Southern Oil Company, an American oil conglomerate responsible for the existence of Las Piedras and most of the region's economy. He tries but fails to get a job through him, but when one of SOC's oil wells explodes, the company tasks O'Brien with putting together a team to deliver enough nitroglycerine to detonate around the fire and literally blow it out.

(This is actually one way to put out an oil fire, and it's the subject of one of Werner Herzog's best documentaries, the epic and biblical Lessons of Darkness.)

The company scrounges two trucks to deliver at least twice as much nitro as they need to extinguish the fire, reasoning that one truck probably won't make it there. Two drivers will be in charge of each truck, and the prize is more than enough money to get out of Las Piedras. Every expat in the town competes for a spot, but O'Brien only gives four of them a chance: Bimba (Peter van Eyck), a tall, taciturn German; Luigi (Folco Lulli), Mario's best friend and roommate until the arrival of Jo; Smerloff, an older Russian, and Mario.

Smerloff doesn't show up for the early morning departure of the trucks so Jo – it's broadly implied that he persuaded the Russian to stay behind, perhaps fatally – sets out with Mario in the larger of the two trucks. They have to drive 300 miles over rutted and unrepaired roads on the other side of a mountain, knowing that their cargo will explode with any unfortunate bump.

The journey across the mountain begins an hour into the picture – almost precisely where I tuned in on that night over fifty years ago. The premise is brutally simple and brilliant, zooming in from the grotesque society of Las Piedras down to the four men, each of whom reveals just enough about himself to make the next ninety minutes compelling.

Until the journey starts, the audience had likely assumed that Bimba, blonde and stereotypically Aryan, was a Nazi who escaped Europe via some bargain basement rat line and ended up in Las Piedras. It turns out he'd watched the Nazis murder his family before spending the war as a slave labourer in a salt mine. Before the trucks leave we already know that the jovial, good-natured Luigi is ill, his lungs destroyed by cement dust from working for SOC, and that he wants the money to go home to Calabria and die.

The revelation is that tough guy Jo, who had bullied his way to the top of the expat community, is a coward in the face of death, and that O'Brien – his oldest "friend" – had wisely chosen not to make him one of the drivers. His former acolyte and sidekick Mario is forced to become the story's hero even though we'd so far seen nothing heroic about him.

Yves Montand was more accomplished as a singer than an actor when he made The Wages of Fear, his ninth picture and first really indelible performance. You can't help but wonder how he'd have fared if Jo had been played by Jean Gabin, Clouzot's first choice for the role; in a story where everybody is basically unsympathetic – Lulli's Luigi is the only one who isn't thoroughly craven or abject – we only gravitate to Montand's Mario because of the performer's looks and charisma.

It's assumed that it took Clouzot to force Montand to rise to the challenge of playing a man like Mario and ultimately make an impression that would lead to subsequent roles with directors like Godard, Costa-Gavras, Tony Richardson, Jules Dassin and Jean-Pierre Melville, and in Hollywood productions like Let's Make Love, My Geisha, Grand Prix and On a Clear Day You Can See Forever.

In Henri-Georges Clouzot: The Enlightened Tyrant, a documentary included with the Criterion edition of The Wages of Fear, actors and collaborators who worked with him describe how he could be a bully on set, emotionally manipulating his actors and even going so far to physically abuse them to extract a performance. Brigitte Bardot, who would star in his 1960 crime drama La verité, called Clouzot "the Devil".

It's easy to believe this after watching the last half of the film, where the drivers are confronted with a series of challenges, like "the Washboard" – a stretch of road they need to take at a crawl or at high speed so that the vibrations don't set off the nitroglycerine. Or a hairpin turn at the edge of a cliff that forces the men to back their trucks on to the collapsing stub of a bridge. Or the massive boulder blocking the road that forces them to team up and use a fraction of their explosive payload to blast the obstacle out of the way.

Clouzot keeps the tension palpable even during lulls in the action thanks to the performances he draws from all four men, and from camera work he had laid out in detailed storyboards on the back of the pages of his script before a foot of film was shot. Some scenes are brilliant, like the one where Jo is rolling a cigarette for Mario when the tobacco is suddenly blown away by a sharp gust of wind – the first silent shock from the blast that vaporizes Bimba and Luigi, who we had seen just a moment earlier in their truck, Bimba shaving to make himself presentable as the end of their journey was in sight.

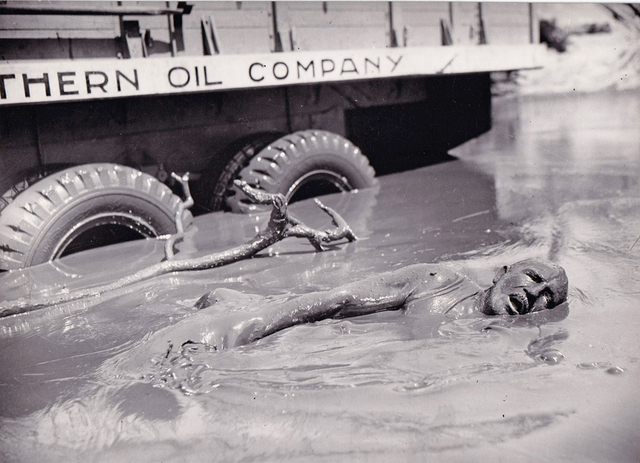

There's nothing left of the truck or the men when Mario and Jo catch up with them, just tire tracks that stop abruptly and a huge crater in the road slowly filling up with oil gushing from the ruptured pipeline that edges the road between the derricks and the storage tanks in Las Piedras. This is the beginning of the most famous sequence in Clouzot's film, where Mario has to drive the truck through the oil before it's too deep while Jo wades through the black ooze pulling obstacles out of the way.

Pinned in place by a tree branch that rises out of the oil like a monster, Mario is forced to drive over his friend to prevent being stuck in the mire. It's the moment this adventure story becomes a horror movie, and nobody can forget it after seeing it – I know I couldn't all those decades ago.

The Wages of Fear is most often described as an existentialist movie, thanks partly to this being the dominant philosophical export of France at the time and to Clouzot's friendship with Sartre. It's an easy assumption to make thanks to the film's bleak, godless setting and the last words of the dying, oil-soaked Jo as Mario drives the final miles to their destination: "There's nothing." It makes the film play like a Camus novel directed by William Wellman.

The Wages of Fear was a massive hit in France, and Clouzot followed it up with the nightmarish thriller Les diaboliques, which also starred his wife Vera alongside Montand's wife, Simone Signoret. By this point Vera's heart trouble was a real issue, made worse by being married to a man who only needed two or three hours of sleep and thought nothing of forcing his wife to do dozens of takes of an emotional breakdown scene in The Spies, his 1957 film about living in a totalitarian society. She would die that same year, of a heart attack she had already portrayed for her husband's camera in the most terrifying scene in Les diaboliques.

When The Wages of Fear was released in the United States it was perceived as anti-American, and called "a picture that is surely one of the most evil ever made" by no less than Time magazine, despite the many cuts made by its distributor. Those cuts couldn't water down the depiction of SOC – the initials blatantly referencing Standard Oil – as a heartless, exploitative corporation intent on risking lives in pursuit of profits. Montand and Clouzot were even called Communists, though the leftist Montand secretly considered his director suspiciously right-wing, no doubt remembering his trial for collaboration at the end of the war.

Defenders of Clouzot argue that he was an equal opportunity hater – a misanthrope whose dismal view of human nature transcended politics; British director Karel Reisz wrote in a 1991 issue of Film Comment that Clouzot was only technically "anti-American" inasmuch as he was "unselectively and impartially anti-everything."

What The Wages of Fear undeniably proved to be was influential. It would be remade by American director Howard Koch for Warner Bros. as Violent Road (also called Hell's Highway) in 1958, and again by William Friedkin in 1977 as Sorcerer – a flop that sabotaged Friedkin's career, though it's developed an ardent following since then and might deserve a look in some future column.

It would be used as the basis for an episode of MacGyver and was remade again last year by Netflix. Its opening shot would be copied in tribute by Sam Peckinpah in The Wild Bunch, and it echoed for decades in films as different as The Train, Army of Shadows Duel, Speed and even Dunkirk, by director Christopher Nolan's own admission.

You could argue that Clouzot's film was itself an echo of earlier pictures like They Drive by Night and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (Montand was, like Jean Gabin before him, often described as a French Humphrey Bogart) and Jules Dassin's Thieves' Highway. The result is that even when marvelling at its originality and groundbreaking direction you might find yourself – like I did as a boy watching late one night – thinking that you had, nonetheless, seen something like it, somewhere, sometime.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.