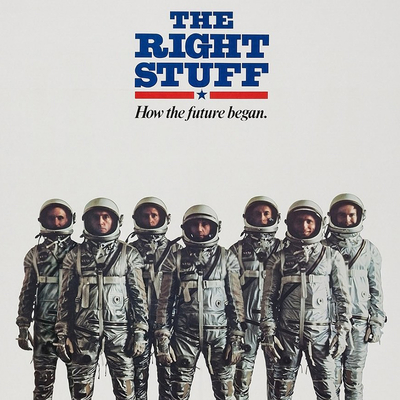

When The Right Stuff was released in the fall of 1983 in prime Oscar season, it had been just two years since America had officially restarted its space program with the launch of the shuttle Columbia. By that point it had been almost a decade since the last Apollo mission, during which it looked like the U.S. was out of the space race after making it to the moon.

It was a good time to release a movie about the pioneering days of NASA and the first astronauts. There had been eight shuttle missions by then with the Columbia's sixth scheduled for the month after The Right Stuff had its premiere at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC. The first woman and the first African American astronaut had gone up on these missions and the whole enterprise harmonized with the optimistic message of the first Reagan administration.

Three years later, though, the Challenger exploded just a month after Christmas, the tenth flight of the shuttle and the twenty-fifth of the space shuttle program – the worst loss of life by NASA since the Apollo 1 fire in 1967. It forced a pause of over two years before another shuttle launch and, along with the breakup of the Columbia on re-entry in 2003, cast a shadow over the program that lasted until its 135th and final flight in 2011.

Writer Tom Wolfe began work on what would become The Right Stuff when he was assigned to cover the Apollo 17 launch, the last moon mission, by Rolling Stone magazine. He worked on the book with breaks to write The Painted Word and complete the collection Mauve Gloves & Madmen, Clutter & Vine and published it in 1979. It became his best-selling book to that point, winning the National Book Award for nonfiction.

Wolfe socialized with producers Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler (Rocky, New York, New York), who bought the rights to Wolfe's book and made a deal with United Artists to make the film. Getting a script together turned out to be more of a challenge: an initial version written by screenwriting legend William Goldman (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, All the President's Men) focused entirely on the astronauts of the Mercury program and disappointed Winkler.

Finding a director was also difficult; Michael Ritchie (The Bad News Bears, Semi-Tough) and John Avildsen (Rocky) both joined and left the project until Chartoff and Winkler came upon Philip Kaufman, who had made several low-budget films (Goldstein, The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid, The White Dawn) before getting fired from The Outlaw Josey Wales. He made a comeback with a remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers and The Wanderers, a period picture about Bronx gangs that led to a brief stint working on the script for Raiders of the Lost Ark.

United Artists was set to shelve the film after the box office disaster of Heaven's Gate, but Winkler and Chartoff moved the film to The Ladd Company while Kaufman set about correcting the major problem the producers had with Goldman's script. In an interview with Vulture Kaufman speculated that "I don't think Bill even liked Tom Wolfe's book that much. From the script, it seemed like he wanted to do a jokey thing about the adventures of the astronauts."

"He'd even created a scene that wasn't in the book where a bunch of the astronauts go to a Mexican whorehouse. I think John Glenn came in to save them or something. It was kind of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid Go to Outer Space feeling."

The problem was that Goldman's script completely left out Chuck Yeager, the legendary fighter ace and test pilot whose story provides a counterpoint to the Mercury astronauts in Wolfe's book. "There was nothing left of Bill's script by the time I got done with my adaptation," Kaufman said. "Bill applied for credit with the Writers Guild, and 99.9 percent of the time in a situation like this, they give the original writer at least a shared credit because they don't want writer-directors coming in and poaching credit. But they gave me the sole credit."

Yeager, as Wolfe describes him, was the prototype for every hot shot pilot, civilian or military, for at least two generations after he became a legend. The folksy drawl – "specifically Appalachian" – that pilots affected had "drifted down from on high, from over the high desert of California, down, down, down, from the upper reaches of the Brotherhood into all phases of American aviation...It was the drawl of the most righteous of all the possessors of the right stuff: Chuck Yeager."

Kaufman's film begins with Yeager (Sam Shepard) at Muroc Air Force Base (now Edwards AFB) on the dry lake beds of California's inland desert, where he's an army air force test pilot who takes on the task of taking up an experimental plane, the Bell X-1, with an eye to breaking the sound barrier. The night before he's supposed to go up he falls from his horse while chasing his high-spirited wife Glennis (Barbara Hershey) in the dark amidst the scrub and Joshua trees.

Yeager shows up with two broken ribs and gets his buddy Ridley (Levon Helm, drummer for The Band) to cut a length off a janitor's broom so he can lever the door of the plane shut with his good arm. He takes the X-1 up and despite warnings from engineers and scientists that the sound barrier is a wall in the air that tears planes apart, Yeager manhandles the rocket plane through Mach-1 and into the history books.

Wolfe does a lot to paint Yeager as the heroic lone wolf – the breaker of records, the man at the pinnacle of the brotherhood of test pilots. Kaufman makes him a cowboy, riding out of the desert to stare down the X-1 as it sits on the desert floor boiling and hissing as it waits for him to fulfil its mechanistic destiny.

Casting Sam Shepard was crucial to this enhancement of his image. Shepard came out of New York City's experimental theatre scene with plays like Cowboy Mouth, The Tooth of Crime, Buried Child and True West, full of marginal characters and dark Americana; when I studied theatre in college he was the epitome of hip, a favorite source for audition monologues, his plays constantly performed by hungry little independent theatre troupes. And somewhere between his brief creative romance with Patti Smith and an affair with Joni Mitchell during Bob Dylan's Rolling Thunder Revue that produced the song "Coyote", he took on the image of the stoic cowboy outsider, irresistible to a certain kind of woman – Leonard Cohen as imagined by John Ford.

He made his debut on film with a minor role in Dylan's Renaldo and Clara and a major one in Terence Malick's Days of Heaven – like Heaven's Gate an infamous flop that's been critically rehabilitated – and followed that by playing opposite Ellen Burstyn in Daniel Petrie's Resurrection. While no physical match for the real Yeager, who was compact, not tall and wiry, he perfectly embodied the ideal of Yeager that Kaufman needed for his picture.

Further down the pyramid of hot shot pilots are younger men like "Gordo" Cooper (Dennis Quaid), a USAF pilot who we meet driving across the desert to his new posting at Muroc, now Edwards, with his wife Trudy (Pamela Reed). Their quarters are rudimentary, the location remote, and the place where pilots go for fun is the Rancho Oro Verde Fly-Inn Dude Ranch, also known as the Happy Bottom Riding Club, run by Florence "Pancho" Barnes, a onetime female aviator and the sort of larger-than-life character you hope you meet in America's remote places (played in the film by Kim Stanley in her last movie role).

Cooper is reunited with two other air force hot shots – "Gus" Grissom (Fred Ward) and "Deke" Slayton (Scott Paulin) – in the second tier at Pancho's and in the social strata of pilots at Edwards, living in the shadow of Yeager. Quaid plays Gordo like a big goofy kid, eager to prove himself, with an ego that hasn't quite justified itself yet.

In Wolfe's book we get to know Gordo through Trudy, as she's pulled along in his wake from air base to air base. We learn about her fears and her recurring nightmare – of the car pulling up in front of their home on the base, the man in the dark suit walking sombrely to their front door to break the bad news. Because one in every four test pilots will die doing his job – "burned beyond recognition" Wolfe writes like a mantra – so it seems like the business of the air force at places like Edwards is to produce widows as much as break records.

We see her look over the dry grass of her lawn to a plume of smoke somewhere in the distance as she confides in the other wives and says that she's moving back with the kids to her parents in San Diego. (Trudy Cooper did separate from her husband while he was at Edwards, but he convinced her to return and help him maintain the wholesome image NASA wanted for their astronauts. She stayed with him through the Mercury and Gemini programs and the Coopers only divorced after Gordo retired from the Apollo program without getting a spot on any mission, but little of this makes it into Kaufman's film.)

Gordo and his friends look like they're doomed to fly in Yeager's exhaust until the Soviet Union launches Sputnik in 1957, sending shockwaves through the U.S. government. Kaufman shifts gears into an extended comic interlude with Jeff Goldblum and Harry Shearer as two operatives tasked with recruiting roster of men to act as the face of America's lunge forward into the space race. They present a list of candidates to a room full of powerful men like Lyndon Johnson (Donald Moffat) – surfers, stock car drivers, acrobats – but get sent out to Edwards to look for pilots.

Sitting in Pancho's they reject Yeager – too independent, not a college man – in favour of younger men like Gordo, Grissom and Slayton. A call goes out that draws in dozens of pilots in uniform – men like Navy flyers Alan Shepard (Scott Glenn), Scott Carpenter (Charles Frank) and "Wally Schirra (Lance Henriksen), and Marine aviator John Glenn (Ed Harris) – a straight arrow who matches the wholesome image the newly created agency wants more than anyone else.

Wolfe's sympathy is with Yeager and the old school test pilots at Edwards, and he writes how they couldn't understand NASA's obsession with putting a man into space at all costs when, as far as they were concerned, the steadily innovating planes they're testing would have done the job sooner or later.

"They watched in consternation as a war effort mentality took over," Wolfe writes. "Catch up! On all fronts! That was the imperative. They could scarcely believe the outcome of a meeting held in Los Angeles in March of 1958. This was an emergency meeting (what emergency?) of government, military, and aircraft industry leaders to discuss the possibility of getting a man into space before the Russians. Suddenly there was no time for orderly progress. To put an X-15B or an X-20 into orbit, with an Edwards rocket pilot aboard, would require rockets that were still three or four years away from delivery."

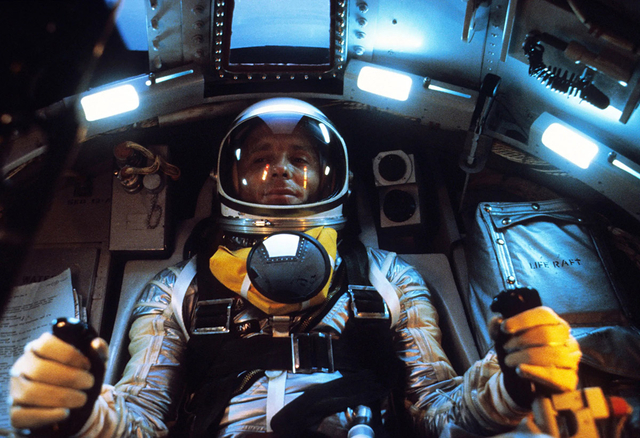

Even worse, the men chosen for these missions would "not be a pilot; he would be a human cannonball. He would not be able to alter the course of the capsule in the slightest. The capsule would go up like a cannonball and come down like a cannonball, splashing into the ocean, with a parachute to slow it down and spare the life of the human specimen inside."

And that man in the capsule "would be an aero-medical test subject and little more." Or as Yeager puts it in the bar at Pancho's: "spam in a can". It's an interesting idea, but it's hard to avoid concluding that putting a man in space, if run by the air force and its test pilot program, would have been far more costly in lives lost.

While the picture focuses on NASA and the astronauts, the main conflict is between Glenn, Gordo and the other men and the technocrats running the program, centred around Scott Beach as a nameless German scientist obviously modeled on onetime Nazi rocket builder Wernher von Braun. They know that their team in the space race is run on political favour and public goodwill to keep public and private money flowing into the program. In other words: No bucks, no Buck Rogers.

They confront the scientists when presented with a prototype capsule and demand that it has a window and a hatch with explosive bolts that can be opened from the inside. At every opportunity they demand as much control as they can get over whatever part of each mission will allow them to elevate themselves above the chimpanzee that beats them all into space. They know they've jumped over the queue of equally qualified pilots with instant celebrity that trumps years of dangerous and unsung test flights. No less than Henry Luce of Time magazine (John Dehner) is generously supplementing their military pay by buying the rights to their stories and those of their wives.

They're as necessary to NASA's story of American enterprise and heroism as the rockets and the payoff could be exceptional: the only thing they have to do is survive from launch to splashdown, which looks increasingly unlikely as the U.S. is plagued with one failed test launch of a rocket after another, while the Soviets go from success to success, culminating in the single orbit of Yuri Gagarin in April of 1961.

The other conflict is between the seven men for that seat in the capsule, a competition won by Alan Shepard with his 15-minute sub-orbital flight three months after Gagarin. Delayed on the launch pad, Kaufman creates an elaborate comic sequence riffing on his need to relieve himself while strapped down in the capsule, then shows the payoff for being the first man, which includes a ticker tape parade and a meeting with President Kennedy at the White House.

This is contrasted with the luckless Grissom, whose capsule sinks after splashdown when the hatch prematurely blows open. He gets no ticker tape parade and no medal presented by the president and, worst of all, his wife Betty (Veronica Cartwright) is cheated of her private audience with Jackie. There's a painful scene with their consolation prize – a vacation in a Florida motel with a fully-stocked fridge and a beach across a busy highway.

It's hard to remember now but The Right Stuff's budget was spent on special effects and not its cast who were, at the time, a group of relative unknowns. Quaid had been an extra in Stripes and had just come off Jaws 3-D; Harris had just done Knightriders and Creepshow, Ward had a small part in Silkwood, Henrikson had parts in Dog Day Afternoon, Network and Close Encounters of the Third Kind while Glenn had been in Nashville and Apocalypse Now.

But they would seem to dominate movies for the next two decades in films like The Silence of the Lambs, The Hunt for Red October, Glengarry Glenn Ross, Apollo 13, Aliens, Near Dark, Henry & June, Tremors, Great Balls of Fire!, Wyatt Earp and The Day After Tomorrow. In hindsight their ensemble performance makes The Right Stuff look like an impossible coup by a studio and several agencies, when in reality it was a big break.

The film cuts back to Yeager at key moments. The last time is when nearly all of the astronauts have had their turn and NASA has proved its worth; they're invited to a hero's celebration at the Sam Houston Coliseum, hosted by no less than LBJ, to announce the opening of the Manned Spacecraft Center.

As they sit with their wives watching Sally Rand perform her famous fan dance, Yeager is at Edwards making a test flight with the NF-104A that takes him to the stratosphere, at the edge of space. Punching through every barrier he gets a glimpse of the stars when the plane goes into an uncontrolled spin. Unable to recover control Yeager is forced to eject and gets burned when oxygen that leaks from his helmet's shattered visor catches fire.

Ridley is riding out with the rescue truck to the crash site when the driver shouts, "Over there – is that a man?"

"You're damn right it is," Ridley responds, to which the audience must reply: "Yes, we get it."

When John Glenn is on his epic series of orbits across the globe he communicates with Gordo on the ground at a remote communications station in the Australian outback, where a group of Aborigines inform him that they know all about traveling in space, and that one of their elders does it all the time.

Glenn doesn't know it yet but the heat shield on his capsule has been damaged and ground control isn't sure if he'll survive re-entry. While he's still orbiting the Aborigines tend to a fire whose sparks seem to explode around Glenn's capsule – Kaufman's very creative explanation for the "fireflies" that the astronaut talked about with wonder, as if encountering alien life.

The magic bonfire seems protect the damaged craft and Glenn makes it back to the ground safely – to a future career in the U.S Senate, and to his eventual return to space on the 92nd space shuttle mission (though no one could have guessed this at the time).

There's an online film critic who insists that The Right Stuff is the last film of the '70s and they may have a point. It's certainly an occasionally very trippy picture, from Glenn's fireflies to the cuts between Yeager at the edge of space and Sally Rand to the special effects created by avant-garde artist and filmmaker Jordan Belson for the picture.

Kaufman's picture is epic – at over three hours long it could have been a roadshow release with overture and intermission – but it's hardly sombre, with its freewheeling shifts from droll comedy to delirious action to domestic drama. William Goldman was probably right that including Yeager with the story of the Mercury astronauts makes The Right Stuff play like two different pictures stitched together. In any cast it got eight Oscar nominations, won four, and launched much of a whole new generation of actors into a Hollywood that would never tell the story of men in space the same way again.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.