The death of Robert Redford has inspired more than the usual somber eulogies, and one dominant message is that Redford was "the last movie star" and that his passing is an elegy, marking the end of Hollywood's best way of getting the most people in front of screens. "A star is different from an actor," wrote Joseph Epstein in the Wall Street Journal. "Stars always play themselves, while actors play characters. In an earlier day, one went to see a John Wayne or a Jane Russell movie, often not bothering to mention, or even learn, the movie's title. Redford, who was 89, was the last such movie star."

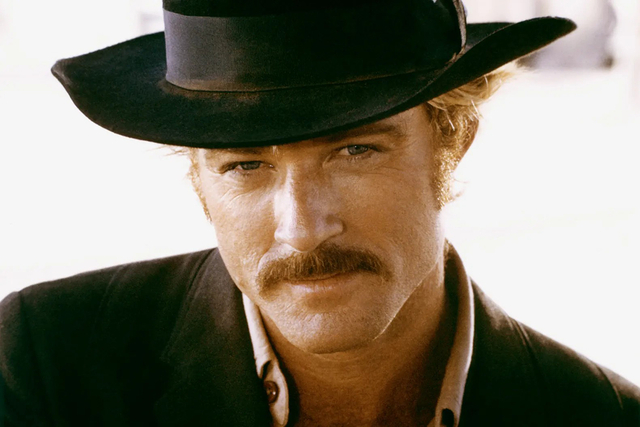

It wasn't enough that Redford was good looking – perhaps even the handsomest man to walk in front of a camera in his heyday. "He possessed an enduring American sensibility – a blend of cool and regal, charm and rebellion," wrote Charles F. McElwee in City Journal. "He broke the generation gap and drew young and old, men and women, to catch a glimpse of him. His looks weathered with age and time."

When I was growing up, the mere mention of his name was the set-up for a comic swoon by women in sitcoms. And there's Mike Nichols' famous story about rejecting Redford for the role Dustin Hoffman would play in The Graduate. "I said, 'You can't play it. You can never play a loser.' And Redford said, 'What do you mean? Of course I can play a loser.' And I said, 'Okay, have you ever struck out with a girl?' and he said, 'What do you mean?' And he wasn't joking."

Ironically, though, it was a buddy film with only a desultory hint at a romance that made Redford's name. Paul Newman was the big star when casting began on Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, going back to his breakout role in his second film, Robert Wise's Somebody Up There Likes Me (1954). By the time director George Roy Hill began pre-production on Butch Cassidy Newman's list of credits included Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Exodus, The Hustler, Hud and Cool Hand Luke.

Redford, by comparison, had been in some interesting flops (War Hunt, Inside Daisy Clover, The Chase) but only one real hit with the film adaptation of Neil Simon's Barefoot in the Park. The producers had offered the role of the Sundance Kid to Jack Lemmon first, and then to Warren Beatty, who also turned it down. Steve McQueen agreed, though he soon dropped out over a dispute over billing with Newman.

Newman suggested Redford, who had the same background in New York theatre, and a lifelong friendship began. It's interesting to imagine the film with a different Sundance: with McQueen it might have been nearly the same picture though the banter between the two men would have been more terse, less affectionate. Beatty has a quality not dissimilar to Johnny Depp – you never feel like he's really sharing the frame with anyone else, bad for a buddy picture – while Lemmon as Sundance would have been a whole different movie, more of a comedy, with an ending that would have landed much more cruelly.

The story of Butch and Sundance was one of the legends of the American West, not quite as famous as the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral but not as obscure as Charlie Goodnight. Hill begins his film with a careful recreation of an old silent western in the style of Edwin Porter's The Great Train Robbery (1903), flickering on the screen while the credits roll. "Most of what follows is true" we're informed.

The film remains sepia-toned when the action begins with Cassidy (Newman) casing a bank he intends to rob. It remains monochrome for a scene where Sundance (Redford) wins at cards with a gunslinger who's ready to challenge him to a duel until he learns who he's up against. The film only opens up into colour as the two men ride off from town and into the vast, dusty landscape of the classic western.

Back at their hideout Butch learns that his leadership of the Hole in the Wall Gang (also called the Wild Bunch – changed because of Sam Peckinpah's film, released the same year) is being contested by the intimidatingly large Logan (Ted Cassidy, The Addams Family's Lurch). Butch is smarter than his men, and quicker to cheat than Logan, who he leaves on the ground after a kick to the groin and a sucker punch.

But he agrees that Logan's idea to rob the Union Pacific train coming and going is a good one, though it draws the attention of the railway bosses, bankers and lawmen who want to pacify the west. In the meantime we get to see how comfortable Butch and Sundance have become with their life of bank holdups and train robberies.

The two men sit on the balcony of a whorehouse watching the town marshal fail to raise a posse, and their drunken banter sketches out their characters. Butch is charming and outgoing, a favorite of the brothel madam, while Sundance is taciturn, a man more comfortable with action (and violence) than words.

Sundance heads off into the night to look for a woman and ends up in the bedroom of Etta (Katharine Ross), the local schoolteacher. He makes her undress at gunpoint – a scene that would raise hackles if anyone tried to film it today, even with the twist that this is roleplay, and that they're already a couple.

This leads to an idyll, famously set to B.J. Thomas' "Raindrops Keep Fallin' on My Head", written by Burt Bacharach and Hal David to a rough cut of the film. Butch shows up at Etta's cabin with a new bicycle and takes her on a joyride around the farmyard. This sets up a romantic triangle between Butch, Etta and Sundance that is teased but never consummated in the picture.

The inclusion of the song has always been divisive – Redford hated it when he saw the finished picture, but changed his mind after the picture made Thomas' song a monster hit. It's definitely a whimsical choice, and a very period-specific one, nailing the picture in place and time. It was a deliberate choice by Hill, meant to mark a high point in the characters' lives, and one that occurs before progressing to a tragic but inevitable end.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is one of the first films I can remember seeing in a theatre with my parents, probably during its 1970 re-release after the Oscars – a list that includes The Railway Children, The Hindenburg, The Sting, The Four Musketeers, The Return of the Pink Panther and (for some inexplicable reason) Costa-Gavras' Z. It's undeniably one of the reasons why I'm doing this today, but even at the time I thought the whole "Raindrops" scene stuck out, mostly because I was just six years old and couldn't understand why they put some song on the radio in a western.

The downfall of Butch and Sundance begins in the next scene, as their comically botched robbery of the Union Pacific train coming back turns lethal when the railways posse of hired gunfighters bursts from a freight car, gunning down most of Butch's gang and sending Butch and Sundance on a chase that takes up nearly a quarter of the film.

Chase scenes – on horseback, over badlands and through canyons, through rivers and streams and across sand dunes – are a staple of westerns, but Hill puts a lot of time and effort into this crucial bit of his story. Our perspective is locked on Butch and Sundance; their pursuers, while named speculatively by the outlaws – remain tiny, distant figures on the horizon.

The sequence is vital because it lets us know who Butch and Sundance are in isolation, and on the run. Screenwriter William Goldman gives Redford and Newman terse, sarcastic repartee as they travel further and further into the wilderness with the posse unerring in its pursuit. It also lets us see how the men are being driven out of the west, finally making a daredevil leap into treacherous rapids as a last, desperate lunge for escape.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is one of those westerns – like The Professionals, Duck You Sucker and The Shootist – set after the west was over as a historic and political moment. Mercantilist America had bridged the continent and men like Butch and Sundance have no place in the shopkeeper's peace it promised. There's even a discussion between Butch, Sundance and Etta about the money E.H. Harriman, head of the Union Pacific, is spending on the mercenary posse he's put on their trail.

"That's bad business," Butch says, outraged. "If he just paid me what he's spendin' to stop robbin' him, I'd stop robbin' him!"

This sends Butch and Sundance to what Butch presumes is the next frontier – Bolivia, a landlocked country high in the Andes that's in the middle of a gold and silver rush like the ones they missed in the American west. It's also among the most politically unstable countries in South America, with nearly two hundred revolutions or coups d'etat since it gained independence in 1825.

After a montage of suitably period stills showing Butch, Sundance and Etta living it up in New York City on their way out of the country, the film dumps them in a roofless train station somewhere in Bolivia, which looks like the kind of country that began falling apart before they could finish building it. When they learn that a language barrier stands in the way of effective bank robberies – Butch had bluffed that he could speak Spanish – they're given a crash Berlitz by Etta and undertake a comic heist where Butch is forced to bark instructions from a crib sheet.

You would presume that making one of the most revisionist of revisionist westerns would put director George Roy Hill smack in the middle of the "Raging Bulls" coterie of American directors who burst out of the carcass of the Hollywood studios like the parasite in Alien. But Hill was actually from an earlier generation who began in theatre and live television, before he made his films like Toys in the Attic, The World of Henry Orient and Thoroughly Modern Millie.

Hill was a professional with ambition who could turn out a hit (The Sting, The World According to Garp) in between flops (Slaughterhouse Five, The Little Drummer Girl) and didn't give his producers heart trouble. Better than a journeyman, he fits more comfortably in with directors like Alan J. Pakula, Sidney Lumet and Arthur Penn.

The film is loosely accurate with the facts of Butch and Sundance's life; screenwriter William Goldman learned about the outlaws in the '50s and opted to turn it into a screenplay to avoid the research he'd need to do to make it a novel. He wrote it to refute the old F. Scott Fitzgerald quote about no second acts in American lives, but every producer he took it to wanted cut out his second act – the half of the film that takes place in Bolivia.

We have a fairly decent idea who Butch Cassidy (born Robert LeRoy Parker) and the Sundance Kid (born Harry Alonzo Longabaugh) were, but Etta Place remains a mystery. Goldman makes her a schoolteacher but most historians agree that she was likely a prostitute; we don't even know if Etta was her real name, and she disappears from history altogether when she leaves Butch and Sundance in Bolivia. Her Wikipedia page is a delightful mess of speculation.

Goldman has fun with all this biographical vagueness by having the men – close friends as far as we can tell – reveal things about themselves during the course of the picture, like their real names, and the fact that Sundance can't swim and that Butch has never killed a man. And even if you'd never heard of them, he lets you know where this is all going with scenes like the one with a friendly sheriff who tells them that they're "two-bit outlaws" and that "your time is over and you're gonna die bloody, and all you can do is choose where."

Etta is even more prophetic when she tells them that she'll go to Bolivia with them and "I won't whine, and I'll sew your socks, and I'll stitch you when you're wounded, and I'll do anything you ask of me except one thing. I won't watch you die. I'll miss that scene if you don't mind." The last line is knowingly anachronistic, but you have to assume that Goldman knew how it would land.

They enjoy a second boomtime in Bolivia despite being so conspicuous, and even take a job guarding a silver mine payroll that goes bad when they're ambushed by bandits. But Bolivian outlaws are portrayed as roughly as competent as Bolivian police and are easily tracked down, leading to a one-sided gun battle where Butch finally crosses his final hurdle as a criminal.

The end comes almost as a surprise, with the two men recognized in a dusty town square. The law corners them and the army shows up and not even Sundance's dead shot can beat those kind of odds. Bolivia says they were buried in the cemetery at San Vicente, after an hours-long gun battle with just three policemen and some authorities, and that one of the men shot the other before killing himself – hardly the blaze of glory in Hill's film. But their graves were never found and Cassidy's family insisted that he returned to the U.S., which has led to a whole cottage industry devoted to Butch's survival.

What's fact is that Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid was a massive hit, winning four of its seven Oscar nominations, but it swept the BAFTAs winning nine out of ten nominations – only Newman lost, to Redford. It turned Robert Redford into a movie star, and the next decade would see him make the pictures that built his reputation – films like Jeremiah Johnson, The Candidate, The Sting, The Way We Were, Three Days of the Condor and All the President's Men.

Good looks – even absurd good looks – will only go so far without talent and charisma, and Redford was the perfect combination. It helped that he never had great ambitions as an actor; a failed painter, he fell into the business with the kind of casual confidence that you'd expect from a handsome man and exuded the sort of coolness you'd expect in kind. He had ambitions as a director, though, and while he made some good films (Ordinary People, A River Runs Through It, The Conspirator) his real gift to filmmaking was founding the Sundance Festival in his beloved Utah as a showcase for independent filmmaking.

When Hill was teamed with Newman and Redford again for The Sting lightning struck twice; the film was a sensation, winning seven out of ten Oscar nominations and putting ragtime music back on the charts. Redford looked for years for a third film that could reunite him with Newman onscreen, but Newman's health declined before they could start production and he made A Walk in the Woods in 2015 with Nick Nolte.

Like Newman he was a bulwark of a Hollywood liberalism that seems to have passed with him. As Armond White wrote in the National Review about Redford's 2007 Lions for Lambs, it's "one of the last instances when a liberal Hollywood filmmaker like director-actor Robert Redford exercised skepticism about political authority. It was made when the legacy media excoriated George W. Bush, before he became a darling of commanding-heights media, which no one in Hollywood expected back then."

"Redford's pretense in Lions for Lambs – as if the news bureaucracy distrusted government bureaucracy – comes from the same facile cynicism on display in Three Days of the Condor, All the President's Men, and The Candidate, made back in the Seventies when he dreamed that the media were our savior. Now that's a fantasy enjoyed by those already in power."

The world changed around Robert Redford the way it changed around Butch and Sundance, on the way to becoming both more regimented and byzantine in its constantly shifting political motility. He came of age in an era where a political assassination wrenched the fabric of existence and didn't get buried in next week's news cycle. As that Sheriff tells Butch and Sundance, "It's over – don't you get that?"

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.