The explosion of really great heist movies proves that there was a lot more going on in the postwar period than an embrace of consumerism and a striving for a well-earned social entente for the middle class. The antihero was being born amidst it all; he was often engaged in the business of taking his percentage of the spoils while nobody was looking, and there was no shortage of respectable wage-earners willing to identify with criminals aching to outsmart the people paying those wages.

The list is impressive, on either side of the Atlantic. From Hollywood there was the archetype – John Huston's The Asphalt Jungle – along with Stanley Kubrick's The Killing, Kansas City Confidential, White Heat, Odds Against Tomorrow, Hitchcock's To Catch a Thief, Criss Cross and at least a dozen more. The English (Operation Amsterdam, The League of Gentlemen), for some reason, leavened their heist pics with comedy (The Ladykillers, The Lavender Hill Mob, Too Many Crooks), as did the Italians (Big Deal on Madonna Street, Audace colpo dei soliti ignoti).

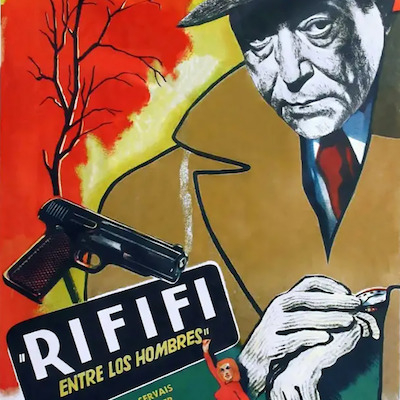

And then there were the French, who regularly produced crime pictures that were grittier and nastier than their Hollywood counterparts. Pictures like Jean-Pierre Melville's Bob Le Flambeur, Henri Verneuil's Any Number Can Win, Jacques Becker's Touchez pas au grisbi and this week's film, considered one of the greatest made on either continent, which might have something to do with its director, an American in exile.

Rififi begins, after stirring titles music by the great Georges Auric, with Tony (Jean Servais) at the card table, losing. He's just finished five years in prison, which has left him with an ominous cough, and all of his friends comment that he's not looking too good. It's not unreasonable to assume that Tony is on his way out, and that whatever transpires in the next two hours will only speed him on his way.

Tony's best friend is Jo "le Suédois" (Carl Möhner), a younger crook for whom Tony took the rap after a failed heist. In gratitude Jo and his wife Louise (Janine Darcey) have named their son Tonio (Dominique Maurin) after him. After rescuing him from the card game, Jo takes Tony to meet with Mario (Robert Manuel), another criminal associate, who pitches him on a quick robbery of a few jewels from the window of the Parisian branch of Mappin & Webb, the British luxury jeweler.

Tony turns them down with the excuse that this kind of heist in broad daylight requires speed, and he's not as fast as he used to be. Jo also lets him know that his ex-girlfriend Mado (Marie Sabouret) is now with Grutter (Marcel Lupovici), a gangster working behind the front of L'Âge d'Or, his nightclub. He pays her a visit at work and invites her back to his apartment, where he humiliates her, ordering her to strip out of her clothes before beating her savagely with a belt.

Director Jules Dassin is asking a lot of his audience this early in the picture, expecting us to sympathize with Tony for the next hour and a half. Villainy, in the world of Rififi, is all relative, and there are worse criminals than Tony – Grutter, for instance, along with his brothers, the icy Louis (Pierre Grasset) and Rémy (Robert Hossein), a junkie. But we won't get to know them for a little while.

For some reason his reunion with Mado makes Tony reconsider the jewelry story robbery, but he tells Jo and Mario that it isn't ambitious enough: he wants to rob the safe, a far more complicated operation for which they'll need a safecracker, and Mario recommends his friend César "le Milanais" (Dassin). They'll need several hours, at night, and access to the owner's apartment above the store, and the caper begins.

The four men become a team, casing the whole street around Mappin & Webb, noting opening and closing times of adjacent shops and the schedule of cops, security guards, postal vans and delivery men. They copy keys and figure out how to disable the high tech (for the Fifties) alarm system. In a New York Times article about heist movies, Dennis Lim recalls John Huston's quote about crime being "only a left-handed form of human endeavor".

"The idea of crime as a line of work –" Lim writes, "hardly an honest one, but a job all the same, requiring an investment of skill and labor – is central to this most process-oriented of cinematic genres."

Jean Servais was a Belgian who played leading men before World War 2 but his career and his health were waning when he was cast as Tony in Rififi. He played a dying man so well that you'd expect to read that it was his last film, but the success of the picture made him a star again. He'd work with Dassin again in He Who Must Die (1957) and with Luis Bunuel in Fever Mounts at El Pao (1959). He would play Free French rear admiral Robert Jaujard in The Longest Day (1962), commencing the naval bombardment of Normandy, and of Gert "Goldfinger" Frobe in particular.

Servais plays Tony as ascetic and unsentimental, reserving what little affection he's willing to show for Jo's son Tonio, his godson. Jo is the outfit's muscle, stolid and capable and loyal to Tony, while Mario and César are almost comic relief; Mario is all appetite, happily in thrall to his sexpot wife Ida (Claude Sylvain), while César is a dandy and, as the kids say today, a hopeless simp, chasing after young women like Viviane (Magali Noël), the singer at the L'Âge d'Or.

Dassin adapted the film from Rififi chez les hommes, a novel by August Le Breton, but France had just become embroiled in a revolt in Algeria and producer Henri Bérard wanted him to change the North African gangsters in the book to Americans. Dassin suggested that it would be easier if they simply made them French, which satisfied Bérard.

Technically, though, it's not quite true, and their nicknames give them away. Jo is "the Swede" while Mario and César ("the Milanese) are Italian, and the latter can't even speak French. Tony is a Frenchman, but his nickname indicates that he's from Saint Etienne, in the south by the Loire, so not a native Parisian. They're all outsiders, and that strengthens their ad hoc bond.

But for the purpose of the heist they're a team, and Dassin devotes a whole half hour of his film to the break-in and safe cracking, a wordless sequence, devoid of any soundtrack music. They chloroform the concierge and his wife but helpfully put a pillow behind the wife while they tie them up. Dassin imagined the heist in detail, from the wool sock on the mallet to soften the blows and avoid tripping the security alarm, to an umbrella lowered through the hole in the store's ceiling to catch debris as they chisel through the floor above.

Dassin even imagines a device like a can opener to carve a hole in the rear of the safe. Some countries like Mexico and Finland banned it or demanded extensive cuts, as they considered it a "how to" guide for ambitious thieves. Dassin insisted that, on the contrary, it showed how difficult it was to become a burglar. The sequence is still regarded as the gold standard for heist movies.

Dassin had gone through five rough years before directing Rififi. After making his name with a series of tough noirs for Mark Hellinger at Universal (Brute Force, The Naked City) and Daryl F. Zanuck at Fox (Thieves' Highway, Night and the City) he'd been named by Edward Dmytryk at the House Un-America Activities Committee (HUAC) and had left America for Europe.

He was supposed to direct a film starring Fernandel and Zsa Zsa Gabor (who the Europeans, he said, thought was a huge star based on her column inches in the press) but heard from Gabor that the film would have a hard time getting shown in the U.S. if his name was on it. Zanuck fed him uncredited work on scripts until he was approached by Bérard to direct a film base on Le Breton's novel.

He didn't like the book, which he had to have read to him by his French agent, and when he took the job out of desperation he wrote the screenplay in English and had his friend René Wheeler translate it into French. When the actor who was cast as César dropped out Dassin took on the role, an American playing an Italian who speaks no French in a French film.

Le Breton's book was a lot darker than the film Dassin ended up making – besides the racial conflict in the underworld there's apparently some necrophilia involved – and he ended up paring it down considerably, to Le Breton's displeasure. The writer, who Dassin describes as having modeled himself on George Raft, confronted him, going so far as to put a gun on the table, but Dassin just laughed and the men ended up great friends.

The title was another problem. It's apparently slang dating back to the First World War, and it appears nowhere in the movie except in a musical number at the L'Âge d'Or, performed by Magali Noël, explaining that it's gangster argot meaning "rough and tumble". Dassin had thought, mistakenly, that it was created by Le Breton to refer to the Rif War in the '20s, and complained that he never liked the number in any case, but his producers insisted it be included for the American market.

Dassin also disagreed with his producers about how to shoot the film, insisting on wasting sunny days and doing location work only when the clouds were out to make Paris a drearier, less picturesque place. It was a brilliant move and contributes to the oppressive mood in the last half of the film, when the Grutters figure out that it was Tony and his gang who did the robbery when César pockets a ring during the robbery and gives it to Viviane, who assumes it's a fake.

While Tony and Jo try to fence their stolen jewels, the Grutters capture César and force him to reveal Mario's address. They try to torture him and his wife but end up killing them. They finally get the ultimate leverage by kidnapping Tonio, and while Jo and his wife try to stall the brothers Tony sets out to search for the boy with Mado's help.

Dassin paints a picture of a city where the underworld is hiding in plain sight, from bars and nightclubs to the drug dealer working out of the back of a dry cleaner. He shows us how, in the city, you're constantly sharing streets and subways with con men, thieves, fences and killers. It's a perfect portrait of a film noir world, where the balance of power between crime and law is liable to shift suddenly, and for reasons invisible to mere citizens.

And it ends well for none of the criminals – neither the "good" ones or their enemies. And despite all the violence the most brutal moment is when, waiting to hear from the Grutters after they snatch the boy in broad daylight, Jo's wife asks him "Where's my baby, you thug?"

As much as I disagree with the Hollywood blacklist on First Amendment principles, I find it hard to consider Dassin one of the more egregious victims of HUAC. Rififi was a huge hit; Dassin won the award for best director at Cannes and his name was kept on the film when it was released in the U.S. Francois Truffaut wrote in Cahiers du Cinema that it was the best film noir he'd ever seen.

By the early '60s Dassin was being backed by U.S. studios for films like Topkapi, his heist comedy, Uptight, his remake of John Ford's The Informer, and Promise at Dawn. Like Joseph Losey, Dassin probably had a more interesting career in Europe than he would have in Hollywood as the studio system collapsed.

The film's success in Europe led to a series of films based on Le Breton's stories, with titles like Du rififi chez les femmes, Du rififi à Tokyo and Du rififi à Paname – not unlike the endless series of spaghetti westerns that would include Trinity or Django in the title.

With its glimpses of nudity and violence, the picture was unlikely to screen in the U.S. without cuts when it was released, dubbed into English, as Rififi...Means Trouble. A challenge by the Catholic Legion of Decency had the producers insert a quote from Proverbs into the titles: "When the wicked are multiplied, crime shall be multiplied: but the just shall see their downfall."

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.