Many people ease into Halloween by watching a scary movie or two. They might be classicists and opt for Universal horror like James Whale's Frankenstein films or Tod Browning's 1931 Dracula. Gentle souls might opt for a haunted romance like The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, while cineastes will choose Kubrick's The Shining or William Friedkin's The Exorcist. Millennials who think they invented irony will go straight to the Scream franchise or horror comedies like Zombieland or Shaun of the Dead.

I want to take you to hell.

More specifically a Japanese hell, as imagined in Nobuo Nakagawa's cult classic Jigoku, which was given the Criterion treatment nearly twenty years ago, putting a once hard-to-find film in a context that includes Japanese new wave films like Woman in the Dunes and The Pornographers and the later explosion of "J-Horror" that includes pictures as different as Battle Royale, Ringu and Tetsuo: The Iron Man.

But mostly I want to see how much interest there is in a film that leaves more dead bodies on the stage at the end than Shakespeare and spends its final act in the infernal region beyond the grave, whose points of interest include, among other things, a river of pus.

Jigoku was the last gasp of Shintoho, a studio on the verge of bankruptcy when Nakagawa started filming in early 1960. The studio had begun with a labour dispute at Toho Studios just after World War II, when a group of employees split off ("Shintoho" literally means "New Toho") and it started promisingly, releasing early films by directors who would become Japanese cinema legends – Akira Kurosawa's Stray Dog and Kon Ichikawa's Design of a Human Being (both 1949) and Kenji Mizoguchi's The Life of Oharu (1952).

Nakagawa would become one of the studio's stalwart directors, best known for his series of kaidan or ghost story films, but despite having a hit in 1959 with Tokaido Yotsuya kaidan – one of many film versions of a classic kabuki play – the studio was going out of business while he was making what he intended as his supreme artistic statement.

Chiho Katsura, one of his friends (and the writer of the wildly surreal 1977 horror movie House) described Shintoho under its final studio boss, the former carnival barker and silent movie narrator Mitsugu Okura, as a "good for nothing studio" best known for making sleazy erotic "pink" movies and garish sci-fi titles like Fearful Attack of the Flying Saucers, Evil Brain from Outer Space and the Super Giant or Starman pictures.

Jigoku is the story of two students: Shirō (Shigeru Amachi) is quiet and serious and engaged to Yukiko (Utako Mitsuya), the only daughter of his university professor. Tamura (Yōichi Numata) is his friend and roommate and a bad influence on Shirō, who knows that his key to success is marrying Yukiko and letting her father prepare the way for his career, in the traditional Japanese fashion. The night Yukiko's parents agree to her engagement to Shirō he gets a ride home from Tamura and fatefully tells him to take a short cut down what Tamura warns is "a bad road".

A drunk staggers out of the dark and into the path of Tamura's car – a yakuza named Tiger (Hiroshi Izumida) whose mother (Kiyoko Tsuji) sees the license plate on the car as they drive off, leaving her son to die on the road. Having lost her husband to a hit and run driver who was never punished, she swears to Tiger's stripper girlfriend Yoko (Akiko Ono) that they'll get revenge.

Wracked with guilt, Shirō pleads with Tamura to go to the police and confess, but his friend feels no remorse at killing "yakuza scum". Shirō confesses to Yukiko, who agrees to go with him to the police station, but on the way their taxi has an accident, killing Yukiko and the driver. Her father is philosophical, saying that it was fate, but her mother is unhinged with grief and blames Shirō.

Shirō spirals into despair and begins drinking at the bar where Yoko works. He takes her home, where she discovers his identity and tells Tiger's mother. But before they can get their revenge, Shirō is called away to the bedside of his dying mother, in the old folks' home that his father runs in the countryside.

There's a lot to absorb at this change of scenery. Shirō's father Gōzō (Hiroshi Hayashi) is sleeping with Kinuko (Akiko Yamashita), who works for him, while also carrying on with the owner of a tavern in town. Ensai (Jun Otomo), once the lover of Shirō's mother, is an alcoholic artist working on a painting of hell for a local temple. His daughter Sachiko, who bears an uncanny resemblance to Shirō's dead girlfriend (also played by Utako Mitsuya) is being pressured to marry Hariya (Hiroshi Shinguji), a corrupt local cop.

Shirō mopes next to the railway tracks when he isn't by his mother's bedside, and one day while he's talking to Sachiko there Tamura suddenly appears. He's warns Shirō that Yukiko's parents intend to pay him a visit and that he himself plans to stay in the country for a while. Kinuko shows up to tell Shirō that his mother has taken a turn for the worse, and to confess that she has feelings for him, and that she wants him to take her back to Tokyo.

Shirō frequently wonders aloud about his friend, who has a habit of appearing as if out of nowhere and doesn't seem to have his best interests at heart. He also knows far more about people and their secrets; he later announces that everyone at his father's old age home bears responsibility for someone's death; even Yukiko's father is burdened by something he did when he was a soldier in Malaya during the war. Not only that, but clocks and watches have a habit of stopping at precisely nine o'clock whenever Tamura is around.

Numata leans into the role of Tamura, his eyebrows perpetually arched, with a manner that's faintly camp and playfully sinister at the same time. The lighting and makeup frequently present him white-faced and lit from below, and he often makes an entrance with a red rose that he drops on Shirō's desk or holds beneath his nose. Numata admitted years later in Building the Inferno, a documentary included with the Criterion release of Jigoku, that he never felt he accomplished what he aimed for as Tamura, but he's the best performance in the film, emanating a thick hint of something infernal before the film fulfills the promise of its title.

Shirō's mother's death hasn't dampened his father's planned celebration of the anniversary of his old folk's home, but before the party can start he gets a visit from Yoko, who has followed him from Tokyo with a gun and intends to shoot him when they meet on a rope bridge over a chasm. He begs forgiveness but before she can get her revenge she trips and falls over the edge to her death. Tamura appears – suddenly, as is his habit – and tells Shirō to do as he says and everything will be alright, but they struggle for the gun and Tamura falls to his death.

But the pace of the storyline has only begun to pick up; that night Gōzō serves tainted fish to his guests but withdraws to a private party of his own with Kinuko and Det. Hariya, Akagawa the dishonest journalist, Kusama the inept doctor and Yamakawa, the fisherman who sold him the tainted fish. Yukiko's parents depart and throw themselves in front of the train; Gōzō discovers his son with Kinuko and accidentally kills her while chasing them to the top floor of his barn.

While Gōzō's guests start to sicken at the party, Tiger's mother shows up to feed poisoned sake to Shirō, Gōzō and his friends. As the poison starts to take effect Tamura suddenly appears, pale and holding a gun. He tries to shoot Shirō and kills Sachiko instead, and while Shirō tries to strangle his friend before the poison can kill him, Tiger's mother wraps her fingers around his throat. In the meantime Ensai has hung himself, after setting his completed painting of hell on fire.

The whole crazed scene is a grand guignol but it's unlikely that the viewer will feel much for all the bodies littering the floors of Gōzō's establishment, except perhaps for Sachiko, the only real innocent. They all bore the guilt of another person's death, as Tamura had gleefully revealed; you'd probably have agreed with the Nietzschean maxim that hell is other people by now, except that the weight of all these dead sinners now presses open the gates of hell itself.

The Buddhist conception of hell – as Yukiko's father explains in a lecture at the start of the film – has eight hot and eight cold levels, individual worlds of torment tailored to the sins of the damned. Jigoku is the Japanese word for hell, and the last act of the film begins with Shirō and Tamura on the banks of the River Sanzu (the Buddhist Styx) preparing for the ordeal to come.

Shirō is joined by Yukiko, who tells him that she was pregnant when she died, and that they need to name the baby that has been born into some analogous limbo – a baby whose cries they hear as it floats down the River Sanzu on a lotus leaf. But before he can do anything the new intake of sinners that arrived, Shirō and Tamura are called before Lord Enma (Kanjuro Arashi), the King of Hell, for judgment.

It's notable that Dante Alighieri's imagining of the Inferno with nine levels is just one more than the eight in jigoku (though if you include both hot and cold hells he was seven short, and that's without taking into account the Purgatorio). Two similar concepts arrived at independently, and Dante echoed the Buddhist inferno with his story of a voyage "into the eternal darkness, into fire and into ice."

What's different, at least if the interpretation in Nakagawa's film is your guide, is that there is a much narrower possibility for redemption here than in Dante's Christian cosmology. Fate takes the lead in plotting your path to jigoku though Shirō's way there was certainly weighted downward by Tamaru's finger on the scales.

Lord Enma judges Tamaru harshly for the sin of abandoning his conscience to evil and allowing himself to become demonic. (Recall that Dante wrote how the "hottest places in hell are reserved for those who, in times of moral crisis, maintain their neutrality" – a sentiment actually harsher than Lord Enma's.) For his punishment Tamaru is dismembered by oni, or demons, only to have his body restored again for a cycle of eternal mutilation. Numata's Tamaru reacts with crazed laughter at the pronouncement of his punishment.

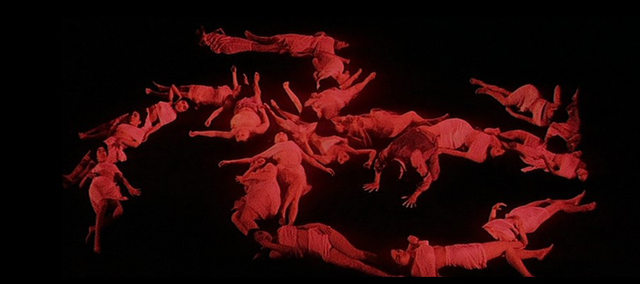

The punishments of hell are portrayed avidly by Nakagawa, on a budget suitable to a midway carnival house of horror but presented with what I can only call sadistic intensity. There's plenty of fire, but also parched earth that swallows water just out of the reach of thirsty souls; there are bodies buried in the ground, hands, feet and heads sprouting from the soil (very much like Gustave Dore's 19th century illustrations of the Inferno). There are oni with implements to shatter teeth and section bodies. There's a forest of glass spikes and, yes, there's that river of boiling pus.

Japan's appetite for stories of vengeful ghosts, cruel oni and forests full of capricious, grotesque spirits easily roused to anger goes back centuries but took a while to find vivid expression in film. Over thirty years ago, a short-lived repertory cinema run by film nerds in my hometown's Chinatown programmed a festival of Japanese ghost story pictures. It was my first chance to see masterpieces like Mizoguchi's Ugetsu (1953), Kaneto Shindō's Onibaba (1964) and Masaki Kobayashi's visually ravishing horror anthology Kwaidan (1964), based on a collection of Japanese folk tales collected by Lafcadio Hearn, one of the first great Japanophiles.

Also on the bill was Shiro Toyoda's relentlessly misanthropic Jigokuhen, or Portrait of Hell (1969), a far more obscure picture. Made very much in the spirit of Nakagawa's Jigoku though with a far bigger budget, Toyoda's film is a testament to the influence of the earlier film, or perhaps just evidence of Japan's abiding taste for gory moral tales.

With Shintoho collapsing into bankruptcy, Nakagawa and his crew had to be very creative, and the director ended up spending his own money to get the film finished. They had the use of a huge soundstage but little money for sets, so the torments of hell are portrayed against inky blacks, and rudimentary special effects were deployed, like coloured dyes swirled in a tub of water. Extras, committed to getting the film finished, were buried in holes that they dug themselves.

At the end, after Shirō struggles to save his daughter by throwing himself on a spinning Dharmachakra, he gets a vision of Yukiko and Sachiko, purified by his sacrifice, beckoning him to the bright light of tengoku (heaven) in the distance. There was no such happy ending for Shintoho, however, and the studio's catalogue was folded back into Toho Studios after its bankruptcy in 1961.

Jigoku was remade – rather loosely – by Tatsumi Kumahiro in 1979 and Teruo Ishii in 1999, then once again in Thailand as Narok in 2005. The consensus is that the first is dull, the second bad, and the third unwatchable. But I'm certain that, for most people, Nobuo Nakagawa's garishly cartoonish original will be more than enough.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.