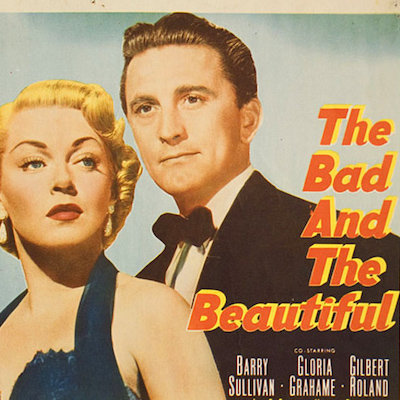

Vincente Minnelli's 1952 movie melodrama The Bad and the Beautiful opens with perhaps the most iconic crane shot ever shown on film. A phone rings on a Hollywood soundstage with a message for the director, Fred Amiel (Barry Sullivan), who is busy rehearsing a shot.

Cut to Amiel behind a camera perched on the end of an iconic piece of Hollywood technology. The camera crane was reputedly invented by no less than D.W. Griffith for his 1916 epic Intolerance, and allowed films to leave the ground and swoop, spin and fly. Massive machines made of iron, steel and aluminum, they required huge crews to assemble, move and maintain safely for the cameraman and assistants perched on the business end, in addition to the motion picture cameras that were ultimately more valuable than their human operators.

Minnelli actually shows Amiel, the director, behind the camera – a rare sight, but it's supposed to be a rehearsal – as the whole machine emerges from the darkness at the back of the soundstage in a curve that ends inches away from an actress in costume, recumbent in a pool of light. You have doubtless seen this shot recycled many times in documentaries, used to evoke the glamour of movies, Hollywood's golden age, or the grand artifice of big budget moviemaking.

Chicago film critic Josh Larsen calls it "a kiss between two cameras" in his review of the picture. "The two cameras converge on the woman," he writes, "but they're really not concerned with her. The shared object of infatuation here is Hollywood itself."

The man on the other end of the line is Jonathan Shields, a movie producer, and we see as he puts in subsequent long-distance calls to Georgia Lorrison (Lana Turner), a movie star, and James Lee Bartlow (Dick Powell), a writer. They all refuse to speak to him; Bartlow is notably succinct: "Drop dead."

But their hostility is briefly overcome, and all three end up paying a late-night visit to the Shields Pictures lot, which is dark, its front gates locked – not a good sign. (The Shields logo is shown here and in the opening credits roll – a generic medieval crest with the motto Non Sans Droit: "Not without right". That this is also the family motto of William Shakespeare suggests that Shields is not without his pretensions.)

They've been invited by Harry Pebbel (Walter Pidgeon), Shields' right-hand man, who is making one last-ditch attempt to convince them to answer a call from his boss, who is apparently somewhere in Europe after the financial collapse of his studio. They warily take their place in Shields' office, significantly glancing at mementos around the room, before Pebbel starts gently pleading for them to overcome whatever has turned them against a man with whom they were once close.

Pebbel begins by appealing to Amiel, a successful director who started his career working at the bottom of the ladder on sets, occasionally picking up the odd job as an assistant director on b-pictures. He met Shields (Kirk Douglas) at his father's funeral, where he cracked wise about the hated old movie mogul while he was being eulogized by no less than former silent star Francis X. Bushman.

It turns out that the crowd around the grave are being paid by Shields at $11 a head, but since Amiel was a wise guy he stiffs him on his fee. Feeling guilty, Amiel drives his jalopy to Shields' dusty, soon-to-be-foreclosed mansion to apologize, where he finds the heir apparent drowning his sorrows. He might have had something to inherit if his father had died a year earlier, but he's come home to nothing.

For some reason Amiel takes a liking to this fortunate son down on his luck and offers to put him up at his place. They become fast friends as Shields is folded into Amiel's circle of Hollywood strivers, including Syd (Paul Stewart) and Amiel's girlfriend Kay (Vanessa Brown). They crash parties to cadge food and drinks – a rite of passage in Hollywood – and Shields decides to buy a spot in a high-stakes poker game where Pebbel, a producer, keeps losing money.

Shields intentionally loses the grub stake his friends have put together and a lot more but uses the debt to persuade Pebbel to put him to work at his studio till he's paid off. He gets Amiel a job alongside him and the two young men work their way up the ladder on low-budget pictures for the poverty row studio. They get assigned to make a horror picture – Duel of the Cat Men, an obvious nod to Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur's Cat People (1942) – and Shields has the Lewtonesque brainstorm of putting all the scares in the dark and off-screen to avoid showing the special effects and costumes they can't afford.

The picture is a surprise hit but instead of making the Cat Men sequel Pebbel wants they persuade him to bankroll a quality script Amiel has been writing, The Faraway Mountain, with a million-dollar budget – on the condition they can get a real star. They manage to persuade Victor Ribera (Gilbert Roland), an amiable cliché of a Latin lover nicknamed "Gaucho", to play the leading man but when Shields negotiates the deal he cuts Amiel out, telling him he's not ready to direct a big picture. Their friendship is over but Amiel goes on to become an Oscar-winning director while his friend sets up his own studio, taking Syd and Pebbel along with him.

It's common knowledge that Orson Welles – a director Minnelli admired greatly – provided at least part of the inspiration for Jonathan Shields, an assumption that's helped by John Houseman's role as producer on the picture. Houseman had found "Memorial to a Bad Man", the Ladies Home Journal short story by George Bradshaw that was provided the bare bones of the story.

But by the time filming began it was hard to ignore how much Shields resembled David O. Selznick, another very hands-on mogul whose father. a pioneer producer and studio head in the silent era, went bankrupt. Selznick, like Shields, was hell-bent on becoming a success as revenge for his father and had gone into self-imposed exile in Europe to make his mistress Jennifer Jones' career his priority after marrying her in 1949.

Minnelli made The Bad and the Beautiful at a high point in his career, between the musicals An American in Paris and The Bandwagon. MGM's Dore Schary wanted him to get another picture out while An American in Paris was still hot but was surprised that he was interested in a script that was, at that point, still called Tribute to a Bad Man. As Emanuel Levy writes in Vincente Minnelli: Hollywood's Dark Dreamer, Schary was shocked that he wanted to make "the story of an out-and-out heel."

The director disagreed, saying that "I think anybody like Jonathan Shields, who has the charm to get people to work for him and get involved with him, must have the charm of this world." He also thought that Kirk Douglas was the only star who could play someone Schary called "a monster."

"Minnelli believed that Douglas was the only star who could effortlessly combine tough harshness with easy charm," Levy writes. "Douglas was the kind of actor who didn't have to portray strength; it came naturally to him. The challenge would be for him to get the character's smooth charm right."

The next flashback is the test of that charm and begins when Shields and Amiel pay a visit to the apparently abandoned mansion of another onetime Hollywood legend, an actor most people would assume was based on John Barrymore. Like Shields after his father's death, his daughter Georgia is living in the dusty, derelict house, an alcoholic who eventually straightens herself up enough to start trying out for bit parts.

Shields decides to take a chance on her against the advice of everyone around him, and casts Georgia in the lead of a historical melodrama opposite Gaucho. She falls off the wagon the night before shooting starts and Shields finds her dead drunk in her squalid apartment. He takes her under his wing and builds her up over the course of filming and she inevitably falls in love with him.

But he doesn't show up for the wrap party meant to celebrate her impending stardom and she finds him at home with Lila (Elaine Stewart), a brassy (but very sexy – Stewart's stymied career remains an abiding Hollywood mystery) bit player that Gaucho got on the picture. Douglas lets loose with some trademark explosive rage when he orders her to go away, which leads to Turner's most vivid scene in the picture, as she races down the Pacific Coast Highway in the rain, sobbing and hysterical as she tries to commit vehicular suicide.

It's Minnelli's best scene, accomplished by putting the car on a huge turntable to make it rock while sweeps in dizzy arcs around Turner. "As lights rake across the screen," Levy writes, "Georgia becomes a blur of white mink and rhinestones. While screaming, she closes her eyes and releases the steering wheel. Her cries are punctuated by various sounds: the rain on the windshield, the stroke of the wiper blades, and the horns of the passing traffic. The car spins and rocks wildly. There's more traffic, more horns, then soft sobs, rain, and windshield wipers."

Back in the present Pebbel reminds her that she left her contract with Shields Pictures as soon as she could and became one of the biggest stars in Hollywood. This brings us to the third former friend in Shields' office, and we flash back to Powell's Bartlow as a relatively content professor at a small Southern university enjoying his summer just as his first novel is being published.

The book catches Shields' eye, and he overcomes Bartlow's resistance to coming west for a couple of weeks, all expenses paid, by appealing to the aspirations of his wife Rosemary (Gloria Grahame), a vivacious but rather shallow southern belle. He sets Bartlow up in his own office to work on the script, even getting his favorite chair and typewriter shipped in, but he's constantly distracted by his giddy, starstruck wife.

Shields commences a bromance with Bartlow that's clearly meant to replace the one he sabotaged with Amiel and takes the writer away to his cabin in the mountains to finish the script together. But while they're away he has Syd, now head press agent at his studio, assign Gaucho to squire Rosemary around town. Driving back to the city after finishing the script, Bartlow sees newspaper headlines describing his wife's death in a plane crash, apparently on her way to Mexico with Gaucho to get a divorce.

Shields convinces him to bury his grief in work, extending his contract to help with the movie version of his book, a civil war epic not unlike Selznick's Gone with the Wind, and like Selznick, Shields decides his vision is greater than any director. He takes over the picture but realizes after screening the final cut that he's made something truly mediocre and orders the film shelved. Bartlow tells him he needs to head back to the mountains to recharge but while they're getting ready to leave Shields accidentally admits his part in Gaucho and Rosemary's death.

Back in the present, Pebbel reminds Bartlow that he's not only one of the most in-demand scriptwriters in Hollywood but that the novel he wrote, inspired by his wife's death, won him a Pulitzer. At the end of this feature-length sales pitch he asks if Shields' three former friends – writer, director and star – are willing to join forces and sign on to a film that will bring Shields back in from the cold, as only their names can attract the necessary money.

They all glance at each other, shrug and turn him down while Pebbel puts in the long-distance call. They're leaving as they hear him deliver his last pitch to Pebbel in the now-empty office, but Georgia reaches for an extension phone to eavesdrop and Amiel and Bartlow lean in, their heads close together as they listen to the man who betrayed them plead for his life.

The.Bad.and.the.Beautiful_03

You can't help but notice while watching The Bad and the Beautiful that the films within the film – Duel of the Cat Men, The Faraway Mountain, the melodrama that makes Georgia a star and The Proud Land, Bartlow's civil war epic – are all pretty terrible, or at least as bad as The Royal Rascal and The Dueling Cavalier, the films within Singin' in the Rain, MGM's big musical hit and another 1952 picture about how Hollywood works.

It's a subtle statement about either the inflated artistic egos that thrive in the movie industry or the generally low taste of the audience for their product, and it would make The Bad and the Beautiful more of a satire if it was intentional – or at least as much of a satire as Singin' in the Rain. But Minnelli wasn't famous for satire as much as his incredible talent for cinematic artifice. Or as Levy puts it in his biography of the director, "Minnelli's art can transform 'corn into caviar,' and, indeed, in this instance, the thrill derives from the unusual combination of dramatic reality and fabricated art."

The Bad and the Beautiful fits decently into that sub-subgenre of Hollywood films about Hollywood – pictures like Souls for Sale, What Price Hollywood?, the first two versions of A Star is Born, Sullivan's Travels, Sunset Boulevard, The Star, The Carpetbaggers, Inside Daisy Clover, The Oscar, The Last Tycoon, Inserts, Barton Fink, The Player, The Artist, Hail, Caesar!, Blonde and the recent Apple miniseries The Studio.

It's a long list and it could have been longer because Hollywood is addicted to ritually exposing itself for its venality and corruption, its crimes against taste and decorum, its bottomless appetite for talent to exploit and for young faces and bodies to paw over with only a notional interest in making a star out of the tiniest minority of either.

But the ritual persists because, like the three former friends prepared to be betrayed again by some infernal genius, audiences are in the habit of excusing Hollywood for its worst excesses in anticipation of being entertained. Or as Levy puts it in his book:

"For Minnelli, The Bad and the Beautiful was about the tawdry absurdities and operatic splendours of the bizarre dream factory known as Hollywood. In his picture, the characters are less conniving, greedy and corrupt; they are more frustrated dreamers who, despite disappointment, still yearn for the art, glamour, and sophistication that movies afford. Having experienced moments of exhilaration, they relish any chance to re-create and relive those moments."

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.