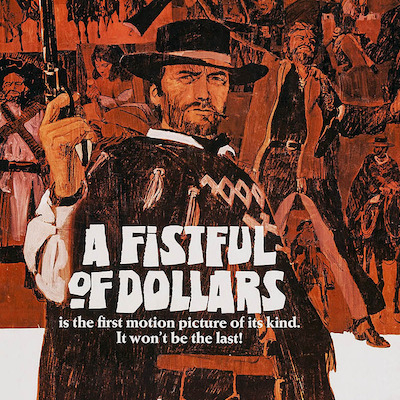

Perhaps because it came out the year I was born, I have a hard time imagining a world without A Fistful of Dollars, Sergio Leone and the spaghetti western. It's easy to forget how much this single film changed not just the western but the movie hero, whose credibility forever afterward came with stubble and unkempt hair, abundant sarcasm and an implacably bad attitude. It became an article of faith that the only honest way to look back at the world arrayed against the hero was through a squint.

By the time I actually understood what a western was, Leone had completed the three films in what would be called the Dollars or the Man with No Name trilogy, though he had no plan to make a series when he finished A Fistful of Dollars. In the meantime the spaghetti western genre had exploded and Leone's films would affect the style and substance of westerns forever afterward. The '60s had begun with John Ford's elegiac The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, but it would end with Sam Peckinpah's brutal The Wild Bunch; something had obviously changed.

The effect of A Fistful of Dollars in North America was delayed by the fact that it wasn't released officially here until over two years after it came out in Italy, when all three of the Dollars films would come out a few months apart in 1967. A publicity campaign by United Artists landed the films in America as a single artistic statement – a fait accompli that they certainly weren't when Leone began production on his ultra low budget western in Spain in the spring of 1964.

Before we even see a frame of Leone's film the picture announces itself with Ennio Morricone's theme music – punctuated with galloping horses and gunshots – and the startling graphics of Iginio Lardani's title sequence – rotoscoped figures on horses, riding across the screen, killing each other in stark red, black and white. It evokes Robert Brownjohn and Maurice Binder's title sequences for the James Bond films (Dr. No and From Russia with Love had already been released, Goldfinger would come out that year) and together with Morricone's music you're put on notice that what follows won't be your average western.

Clint Eastwood arrives onscreen with his unnamed gunslinger fully formed, in his brown suede boots and jeans, sheepskin vest and poncho, teeth gripping a cheroot. He's on a mule – a sign that he's down on his luck – and stops for water at a well on the edge of a town where two white-painted adobe houses face each other.

A little boy sneaks out the door of one house and climbs into the window of the other, before he's kicked out the door by a fat surly man who encourages him to go back home by shooting the ground around the boy with a pistol while he wails that he just wants to see his mother. Eastwood watches all of this with an impassive eye, noting Marisol (Marianne Koch), the mother, watching helplessly.

Venturing further into town while citizens eye him from behind doors and window shutters, he passes a dead man on a horse, riding the other way out of town, a sign reading "Adios Amigo" pinned to his back. He's met by Juan (Antonio Moreno), the half-mad town bellringer, who tells him that San Miguel is a great place – if you want to get rich or get dead.

The town is run by two gangs run by the Baxter and Rojo families, who are in turn at war with each other. When he's harassed by a gang of Baxter goons he takes refuge in the cantina run by Silvanito (Pepe Calvo), who lets him know that the more dangerous of the two gangs is probably the Rojos, led by Ramon (Gian Maria Volonte), a narcissistic sociopath who occupies a spot between his businesslike older brother Don Benito (Antonio Prieto) and the psychopathic Esteban (Sieghardt Rupp).

Musing to Silvanito that he's right between the two gangs, he offers his services to Don Benito, then walks across the town square to confront the Baxter goons who greeted him a few moments earlier. As he passes Piripero (Joseph Egger), the town undertaker, he tells him to get three coffins ready. He goads the Baxter men, then easily outdraws them in a lightning gun battle. Walking back across the square he apologizes to Piripero: "My mistake. Four coffins."

San Miguel is one of a long series of nightmare towns in western films like Last Train From Gun Hill and Warlock, and Eastwood would later ride into one of the worst ever imagined in his film High Plains Drifter. They're places where law and order have yet to arrive or where the law has been suborned by whatever special interest or frontier tyrant holds sway over the place; in Leone's film John Baxter (Wolfgang Lukschy) is the town's sheriff, though he does nothing to control the worst impulses of his own men or the Rojas.

Anybody who knows anything about Leone knows that A Fistful of Dollars began as a rewrite of Akira Kurosawa's samurai film Yojimbo, which was itself inspired by the 1942 movie version of Dashiell Hammett's novel The Glass Key as well – if you believe other accounts – as his novel Red Harvest. Different accounts recall Leone seeing Kurosawa's film up to many dozens of times and even screening it on a Moviola while he was working on his script.

When Leone started work on his movie the Italian movie industry was in a sorry state and he and his friends had barely worked for many months. American productions who had filled the soundstages at Cinecitta had disappeared after the box office disasters of Sodom and Gomorrah and Cleopatra. It had been almost three years since he'd made his directorial debut, the sword and sandal epic The Colossus of Rhodes, and it looked like he'd never get a chance to make a film with that kind of budget again.

When Leone finally cobbled together funding from a combination of Italian, Spanish and West German producers who had him save money by filming in Franco's Spain, he set about casting for the film still called The Magnificent Stranger. His first choice – Henry Fonda – was a pipe dream; Fonda's Los Angeles agent didn't even bother showing him a script. Charles Bronson saw a script but didn't like it, recalling a bad translation from Italian into English with some laughable attempts at western slang. James Coburn was interested but Leone could only afford to pay his lead actor $15,000 and Coburn wanted $10,000 more than that. He would ultimately work with them all – Coburn in Duck, You Sucker! (also called A Fistful of Dynamite) and Fonda and Bronson on his masterpiece, Once Upon a Time in the West.

What he could afford was a young American whose movie career had been going nowhere when he was cast in Rawhide, a popular TV series that ran on CBS for eight seasons from 1959 to 1965. Leone was sent a copy of an episode of the show and some publicity glossies; he couldn't watch more than half of the show but liked how Eastwood moved. His character, Rowdy Yates, was too young for his nameless gunman but he drew stubble and a cheroot on the glossy and gave in to the pressure from his producers to cast someone now while the money was still available.

Eastwood claims that he bought most of the wardrobe items for his character – the hat, the sheepskin vest and a pair of San Francisco or "Frisco" jeans (a generic term for Levis) – in a wardrobe shop on Santa Monica Boulevard and brought them to the shoot, along with a pair of pistol grips with a silver snake on them and the brown suede boots he wore on Rawhide. He also says he brought the poncho with him, but Leone disagreed and evidence, including a sketch made for the character before Eastwood was cast, is on his side.

The only part of his character's wardrobe that Eastwood disliked was the toscano cigar; he said he kept several lengths with him to clench in his teeth without having to light them, and added that "if I had to be in an unpleasant frame of mind, I took a couple of draws and boy, I was right there." I can concur with this: when I was young and intent on smoking everything legal and illegal I got my hands on a pack of toscanos, once I'd worked my way through Gaulouises and Sobranies. It was not unlike sucking the fumes from an oil fire.

The actor didn't think much of the project but says that he took it for the chance of a holiday in Rome and Spain – places he'd never been. Leone spoke no English and Eastwood no Italian so they communicated with gestures or with the help of Elena Dressler, a Polish woman working for the German producers who'd learned English from American soldiers after she was liberated from a concentration camp.

Facilities on set in Spain were primitive, and Eastwood recalls cast and crew going behind trees to relieve themselves. The province of Almeria was one of the least developed in the country so it was an easy place to find vistas uninterrupted by roads or telephone poles, and there plenty of rough adobe buildings that looked like something you'd find in the Mexican border territory. Comparisons of shooting locations with modern views show changed landscapes, with highways, wind farms, industrial greenhouses and holiday homes inserted into what were stretches of rocky, brown hills.

Budget was also a problem: it was low enough without the Spanish co-producer failing to contribute his share after the first installment. Arrigo Colombo, one of the Italian producers, had to smuggle 30 million lire across the border into Spain, risking jail if he was caught. Crew went unpaid and at one point Eastwood walked off the set and Leone was able to talk him into staying before he left his hotel for the airport. Money ran out in the final week, when Leone and Colombo had to cut anything in a scene that cost money; in the end most of the cast and crew were sent back to Rome and Leone finished the film with just three actors and fifteen crew, with the owner of the land where they were filming providing them credit and the electricity to finish.

Gian Maria Volonte, playing the dangerously impulsive Ramon, was known as a theatrical actor and that caused problems for Leone, who had to work to curb his histrionics in front of the camera. Volonte was very political and refused to work on projects that didn't align with his leftist politics – very much in vogue in Italy's stage and movie business at the time. (He would later star in Elio Petri's Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, Giuliano Montaldo's Sacco & Vanzetti and Francesco Rosi's Christ Stopped at Eboli.) Leone doubtless shared these sympathies, but by the time he made Duck, You Sucker! he was becoming disillusioned with politics.

Eastwood's other co-star in the picture was Marianne Koch as Marisol – a woman Ramon is in love with who he keeps after falsely accusing her husband of cheating at cards. Koch (whose credits include Scandal at the Girls' School, The Italians They Are Crazy and The Hell of Manitoba) has an almost wordless part, with far fewer lines than the only other woman in the picture – Margherita Lozano as Consuelo, the matriarch of the Baxter clan. Koch gets knocked cold by Eastwood and used as a bargaining chip when the Rojos capture Antonio, the Baxter's son.

Marisol isn't a romantic interest for the film's hero as much as a symbol, which becomes obvious when she's briefly reunited with her husband and her son, Jesus, during the prisoner exchange in the town square. They're the holy family – Jesus, Mary and Joseph – and saving them is the only display of sentiment Eastwood's character shows during the picture, and gets him brutally beaten by the Rojos and their men before he manages to escape, with Piripero's help, in a coffin. Leone, who considered Grace Kelly the only flaw in High Noon, pointedly took women out of his westerns, only making an exception for Claudia Cardinale's Jill, the New Orleans whore who tried to make a new start on the frontier, in Once Upon a Time in the West.

Eastwood's escape prompts the most violent scene in the picture, as the Rojos assume that he's hiding with the Baxters and Ramon decides the time has come to end their rivalry. We'd watch him massacre a company of Mexican cavalry with a machine gun earlier in the picture. (Leone would re-use this in Duck, You Sucker! He was fond of recycling scenes, like the gunfight in the round that concludes both For A Few Dollars More and The Good, The Bad and The Ugly.) But this scene confirms what would have been obvious to anyone early in the film – that the Rojos were more unhinged killers than the Baxters.

The end of the feuding clans in San Miguel is a perfect example of the kind of ultraviolence that marked the spaghetti western from its start. First Ramon sets off explosives around the Baxter hacienda, then he has his men drive up in wagons and roll barrels of gunpowder against the ground floor door and windows. His men shoot Baxter's gunmen as they try to escape the flaming building, and gun down Baxter and his son when they plead for mercy. Finally Esteban shoots Consuelo while she wails over their bodies – a cold-blooded move that even shocks Ramon. It's a hellish scene.

Westerns could be violent, but this looked like Leone audaciously kicking down one of the remaining rules that governed motion pictures. In his essential book Sergio Leone: Something to do with Death, Christopher Frayling states that Eastwood didn't think Leone's take on violence was a conscious defiance of the old production code rule that a fired gun and the target of its bullet couldn't appear in the same shot. "You had to shoot separately," Eastwood said, "and then show the person fall. And that was always thought sort of stupid, but on television we always did it that way."

"And you see, Sergio never knew that, and so he was tying it up... You see the bullet go off, you see the gun fire, you see the guy fall, and it had never been done this way before."

There had, of course, been violence and sadism in westerns, but Leone's innovation was both a matter of degree and the cool moral distance with which his protagonist, the nameless gunman, observes the violence. The film begins with a fat thug shooting at the feet of a child as he cries for his mother, and ends with the torture of Silvanito, the only kind person Eastwood meets in San Miguel. It's a setup for the final showdown – a duel in two parts where Eastwood finishes off what's left of the Rojos before taking on Ramon. His job done and San Miguel free (for now), he rides off with his saddle bags full of the money that brought him there.

Leone's film famously opened in a single theatre in Florence with no premiere or advertising and somehow garnered enough word of mouth that it ran for months and became a sensation in Italy. Getting it released in North America was made more difficult by the lawsuit brought by Kurosawa and Toho Studios when Yojimbo was conspicuously left out of the film's credits. Leone had received a personal letter from Kurosawa that began "Signor Leone – I have just had the chance to see your film. It is a very fine film, but it is my film..." Leone was so flattered by what he perceived as praise from one of his idols that he couldn't see the legal threat in the letter.

In the meantime Eastwood, back at work on Rawhide, read a story in Variety about the surprising success of a film called A Fistful of Dollars in Italy, but since no one had told him that the title of the picture had been changed from The Magnificent Stranger, he took no notice. "The production hadn't bothered to write to me since I left," he remembered, "to say thank you or go screw yourself or whatever."

The other shoe wouldn't drop until near the end of the year, when Variety's Rome correspondent wrote about the film after it had its belated official premiere at the city's Supercinema. He described a "crackerjack western" made by an international cast "with James Bondian vigour", and noted the performance of its lead, Clint Eastwood, whose performance shaped "a character strong enough to beg a sequel." Perhaps there would be life after Rawhide after all.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.