Beyond The Mark Steyn Show:

Columns, poems, tales, music, movies and more from Mark and friends

Laura's Links

Graduating from HamasU

Greetings one and all and welcome to the Passover 2024 edition of Laura's Links. After many hours of toil, the Cohen household was Kosher for Passover on Sunday last week, just in time to cook up a storm for the Seder that we hosted. The story of the Exodus was told, all the songs and psalms were sung. The festive meal was eaten and it was just tremendous to have a house full of light and (almost all of) the people that I love the most. Subsequent intermediary days of the holiday have been quite nice as well, although it has been a little nippy outside for my taste, given that it's almost May! GAH! I was offline for the actual holiday days: no phone, electronics etc. But once I fired up the computer, I was very interested to get caught up ...

Clubland Q&A

Live Around the Planet: Wednesday April 24th

Mark takes questions from Steyn Club members around the world...

Steyn's Song of the Week

The Days of Wine and Roses

Mark celebrates the centenary of Henry Mancini...

Rick's Flicks

Island in the Sun: Pietro Germi's Seduced and Abandoned

Rick McGinnis on a 1964 Italian comedy...

The Mark Steyn Audio Show

Muscle from Brussels

Mark answers questions on many topics, from a Belgian mayor's assault on free speech to jury selection in New York and Washington...

Politics & Current Affairs

The Habits of Liberty

Steyn is interviewed by Frank Haviland of The New Conservative...

The War on Free Speech

Getting the Message

Steyn files three new motions in the DC Superior Court...

A Clubman's Notes

The Waterloo Hustle

It's time for Part Seven of my latest Tale for Our Time: The Secret Adversary, with Agatha Christie venturing from country-house murders at St Mary Mead into the high stakes of post-Great War politics. Mike Clifson, a Mark Steyn Club member from Cartagena (no, not the Cartagena of "Cartagena hookers" fame, the one in Spain) writes: I haven't thanked you for the enjoyable listening! I haven't reread this book for about forty years and first read it under ten about seventy-five years ago with a rather cub-scout idea of the byplay between the heroine and the hero which I rather skipped thru .... I had not expected listening to be more enjoyable than rereading again on a plane flight or during yet another burst of flu, but it sure is, and the ...

A Clubman's Notes

Weak and Shifty at the Corner House

Part Six of our nightly audio entertainment - The Secret Adversary, an early Agatha Christie caper of Tommy & Tuppence attempting to scuttle coup-fomenting Bolshevists on the mean streets of London...

A Clubman's Notes

Sure Thing at the Ritz

Part Five of a rather English adventure: an Agatha Christie caper set amidst Bolshevist plots on the streets of London - The Secret Adversary...

A Clubman's Notes

The Oilskin Packet

Part Four of our latest audio diversion: The Secret Adversary - Agatha Christie's 1922 caper set in a London seething with Bolshevists and labour unrest...

A Clubman's Notes

The Grill Room Awaits

Welcome to Episode Three of Agatha Christie's tale of Bolshevist revolution looming on the streets of London...

A Clubman's Notes

Through an Estonian Glass Darkly

Welcome to Part Two of The Secret Adversary by Agatha Christie, our latest audio adventure in Tales for Our Time and set amidst Bolshevik intrigue on the streets of London...

A Clubman's Notes

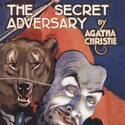

The Young Adventurers, Ltd

Welcome to the sixty-second audio adventure in our series Tales for Our Time - and our second venture into the work of the world's bestselling author, Agatha Christie...

The Mark Steyn Audio Show

Conrad Black on the Dirty Stinking Rotten Corrupt US "Justice" System

Mark talks to his old boss, the Rt Hon the Lord Black of Crossharbour...

Tales for Our Time

The Prisoner of Windsor

A remote fantastical kingdom far from Europe's chancelleries of power... An unpopular monarch on the eve of his coronation... A ruling class of plotters and would-be usurpers... ...and a gentleman adventurer on holiday. No, not Ruritania in the nineteenth century, but the United Kingdom in the twenty-first...

A Clubman's Notes

After the Match

Tales for Our Time returns with a Steyn take on an H G Wells theme...